A Secret Library, Digitally Excavated

Source: newyorker.com

Just over a thousand years ago, someone sealed up a chamber in a cave outside the oasis town of Dunhuang, on the edge of the Gobi Desert in western China. The chamber was filled with more than five hundred cubic feet of bundled manuscripts. They sat there, hidden, for the next nine hundred years. When the room, which came to be known as the Dunhuang Library, was finally opened in 1900, it was hailed as one of the great archaeological discoveries of the twentieth century, on par with Tutankhamun’s tomb and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

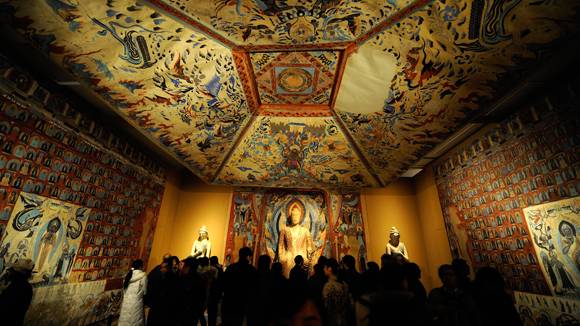

The library was discovered by accident. In the early Middle Ages, Dunhuang had been a flourishing city-state. It had also long been famous as a center of Buddhist worship; pilgrims travelled great distances to visit its cave shrines, comprised of hundreds of lavishly decorated caverns carved into a cliff on the city’s outskirts. But by the early twentieth century, the town was a backwater, and its caves had fallen into disrepair. Wang Yuanlu, an itinerant Taoist monk, appointed himself their caretaker. One day, he noticed his cigarette smoke wafting toward the back wall of a large cave shrine. Curious, he knocked down the wall, and found a mountain of documents, piled almost ten feet high.

Although he couldn’t read the ancient scripts, Wang knew he had found something of incredible significance. He contacted local officials and offered to send the materials to the provincial capital; strapped for cash and preoccupied with the Boxer Rebellion, they refused. Soon, however, rumors of the discovery began to spread along the caravan routes of Xinjiang. One of the first to hear about it was the Hungarian-born Indologist and explorer Aurel Stein, who was then in the middle of his second archaeological expedition to Central Asia.

Stein rushed to Dunhuang, and, after waiting for two months, he finally met with Wang. Negotiations were delicate. Wang didn’t want to let any of the documents out of his sight, and was uneasy about selling them. Stein prevailed, eventually persuading the monk by invoking his patron saint, Xuanzang, a Chinese pilgrim who made an arduous journey to India in search of religious texts in the seventh century A.D. Claiming to be following in Xuanzang’s footsteps, Stein convinced Wang to sell him some ten thousand documents and painted scrolls for a hundred and thirty pounds.

News of the Dunhuang Library set off a manuscript race among the European powers.

[...]

Read the full article at: newyorker.com