Britain and banking: Back to the 1830s

Source: blogs.independent.co.uk

Unparalleled levels of imprudent lending; corrupt banking practices; soaring inflation and rising unemployment; government bank bailouts and an economy dependent on increasing levels of debt to sustain growth. Sound familiar? It would have done to Britons in the 1830s. The fact is that we have been in a remarkably similar economic crisis before and the reasons for it could be almost identical.In Britain during the early 19th century, paper money was not as we know it today – all reassuringly bearing the head of the Queen and the stamp of the Bank of England. Back then, the Bank of England had the monopoly on the creation of metal coins but private banks – literally – had a license to print money of the paper variety and stick whatever images they liked on it. The result of the bank’s power to print money had disastrous consequences: inflation, as too much money flooded the economy and unsustainable lending, as banks lent out more in paper money than they could possibly back up with real reserves.

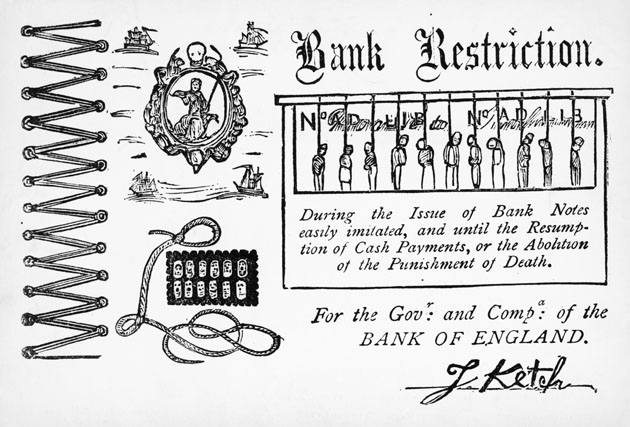

George Cruikshank’s famous bank note of 1819, a comment on stringent measures to protect the paper currency by hanging forgers. (Getty Images)

When the bubble finally burst in the late 1830s, catalysed by a similar crisis in America (sounding familiar again?) the ensuing lack of confidence in the system led to a run on the banks which had to be hastily curtailed by the Bank of England bailing out a prominent northern bank (how about that one?). In 1839 a similar predicament forced the Bank of England into the ignominious position of having to borrow £2 million from France.

The problem was ultimately resolved by an act of parliament. In 1844 the Bank Charter Act curbed the private banks’ ability to create paper money and ultimately phased it out altogether. The power to create money was now solely in the hands of the Bank of England, a situation which today we think of as the norm, so much so, in fact, that money being created willy-nilly by any private organisation with sufficient (or even insufficient) funds is pretty much unthinkable.

But wait a minute, because, unthinkable as it may be, that’s exactly what is going on today. The causes of our modern banking crisis may be uncomfortably similar to what happened in the 1830s. Today it’s not paper money that the banks have a license to print, but electronic money.

[...]

Read the full article at: independent.co.uk