How Steve Jobs Turned Technology — And Apple — Into Religion

Source: redicecreations

A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on.

~John F. Kennedy

Steve Jobs being dead hasn’t diminished the power of his name, or the Apple brand. In fact, it has only reinforced the ’spirituality’ of the company he left behind - the company, many can demonstrate, has been deliberately honed into a cult-like religious orthodoxy.

Brett T. Robinson, author of Appletopia: Media Technology and the Religious Imagination of Steve Jobs describes in several articles how Jobs crafted a business model that makes products and a brand a ’gateway to enlightenment’, how brick-and-mortar storefronts act as cathedrals, and how Jobs transformed modern western culture to have faith that "technology always means human progress".

Following, Red Ice TV goes into the occult origins of the Apple logo in Symbolism In Logos, and how it is used to reinforce ideas of religiosity in consumer products.

How Steve Jobs Turned Technology — And Apple — Into Religion

By Brett T. Robinson | Wired

“Much ink has been spilled drafting the Steve Jobs encomium. But Jobs and Apple are interesting for far more than technological prowess — they provide an allegory for reading religion in the information age. They are further evidence that shifts in popular religion throughout history are accompanied by changes in the media environment: when the dominant modes of communication change, so do the frameworks for religious belief. Still, this shift would require a fitting mythology…

An ancient Egyptian myth helps illuminate the perennial relationship between media forms and metaphysical belief systems. The Egyptian god Theuth visits King Thamus to show him that writing “once learned, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memory.” Thamus replies by admonishing Theuth that his affection for writing prevents him from acknowledging its pitfalls. Writing does not improve memory but makes students more forgetful because they stop internalizing information. Writing also exposes students to ideas without requiring careful contemplation, meaning they will have “the appearance of wisdom” without true knowledge.

The celebration of technological values in the Apple story requires a similar response. The technological values promoted by Apple are part of the Faustian bargain of technology, which both giveth and taketh away.

King Thamus’ anxieties about the new media of writing threatening wisdom have been resurrected in digital form. But Jobs confronted the technology paradox by imagining technology as a tool for expanding human consciousness rather than as a means of escape from it. The tension between technology and spirituality was not a zero-sum game for him.

Jobs’ Zen master Kobun Chino told him that he “could keep in touch with his spiritual side while running a business.” So in true Zen fashion, Jobs avoided thinking of technology and spirituality in dualistic terms. But what really set him apart was his ability to educate the public about personal computing in both practical and mythic ways.

The iconography of the Apple computer company, the advertisements, and the device screens of the Macintosh, iPod, iPhone, and iPad are visual expressions of Jobs’ imaginative marriage of spiritual science and modern technology.

Apple Ads as Parables

Technology ads provide parables and proverbs for navigating the complexities of the new technological order. They instruct the consumer on how to live the “good life” in the technological age.

Technology ads provide parables and proverbs for navigating the complexities of the new technological order. They instruct the consumer on how to live the “good life” in the technological age.Like all advertising, Apple’s ads perform a vital educational function in consumer society. The advertisements are allegorical, rhetorical attempts to domesticate foreign and abstract concepts, making them accessible and attractive to everyday adherents.

In fact, they resemble medieval morality plays in their personification of good (Mac) and evil (PC). As such, the ads contain a moral — or, more explicitly, they propose a morality customized for the conditions of the age.

Media technology has acquired a moral status because it has become part of the natural order of things. Luddites, those who have sworn off new technologies, are the new heretics and illiterates. Technology is an absolute. There is no turning back or imagining a different social order. Challenge is acceptable as long as it remains within the confines of the technological order. Apple may challenge Microsoft. Samsung may challenge Apple. But the order must not be challenged.

The impact of digital culture, then, is epistemic; it insinuates a moral system based on its own internal logic.

The underlying message of the early Mac versus PC ads is not simply that the Apple operating system is superior. The ads carry the implicit assertion that technology always means human progress.

In addition, the personification of the operating systems by actors reinforces the notion that computers are extensions of the human person. In this sense, the ads are not dualistic at all. Good and evil, Mac and PC, man and machine are married in service of the progress myth.

The religion of technology is practiced in the ritual use of technology and the worship of the self that the technologies ultimately foster.

Enter the Paradox

In the Greek Narcissus myth, the young man is captivated by his reflection in a pool of water. Marshall McLuhan reminds us that Narcissus was not admiring himself but mistook the reflection in the water for another person. The point of the myth for McLuhan is the fact that “men at once become fascinated by an extension of themselves in any material other than themselves.”

Eastern wisdom traditions seem fitting antidotes for correcting the addiction and narcissism fostered by media technologies. The Wisdom 2.0 conference, for example, held annually in California invites participants to learn techniques for living with “greater presence, meaning, and mindfulness in the technology age.” But the wisdom traditions themselves have been subsumed by the logic of popular technology and consumerism. Participants pay upward of $1,500 to learn mindfulness techniques from “the founders of Facebook, Twitter, eBay, Zynga, and PayPal, along with wisdom teachers from various traditions.”

The top billing at the conference naturally belongs to the technology gurus rather than the spiritual ones. And this confusion of technological values with religious or spiritual ones is a product of a key rhetorical trait shared by both: the paradox.

To the nonbeliever, the paradoxes of religion are absurd and irrational diversions.

To the true believer, however, they are pathways to enlightenment.

Jobs’ affinity for paradox in his technological and spiritual thinking may be partly attributed to his “inexhaustible interest” in the works of William Blake, an eighteenth-century romantic poet and mystic who, like Jobs, was a multimedia artist who reveled in religious satire. Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell was a combination of poems, prose, and illustrations produced on a series of etched plates — an eighteenth-century iPad, if you will.

In a critique of the puritanical sentiment sweeping England in the late eighteenth century, Blake presents a series of paradoxes aimed at subverting conventional dualisms. In his Proverbs of Hell, he shared that “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom” and “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” Blake used the poem and illustrated plates to subvert traditional dualisms, to propose an alternative cosmology in which good and evil were complementary forces for human flourishing. Heaven represented restraint, while hell represented the creative passions that give humans their joy and energy; the two worked together in harmony to facilitate a more enlightened state of being.

Steve Jobs resolved the paradoxes posed by technology in the same spirit.

Technology is a powerful medium for creative expression, but absent restraint it has the potential to breed an enslaving addiction. Echoes of Blake’s paradoxical style can be heard in the advertising rhetoric of the Apple computer company. Some of the best proverbs come from the company’s most iconic campaigns:

See why 1984 won’t be like “1984” (1984 Macintosh)

While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius (1997 “Think Different” campaign)

Less is more (2003 PowerBook G4)

Random is the new order (2005 iPod shuffle)

Touching is believing (2007 iPhone)

Small is huge (2009 Mac mini)

The iPhone 5 launch in September 2012 announced “The biggest thing to happen to iPhone since iPhone” and “So much more than before. And so much less, too.”

Jobs embraced elliptical thinking as a means of promoting technology objects that pose their own paradoxes. In the Apple narrative, the seemingly oppositional notions of assimilation/isolation and freedom/enslavement are resolved by Apple’s invocation of enlightened paradox.

The paradox today is that new media technologies connect us to more people in more places. (Marshall McLuhan’s “global village” has been invoked more than once). But at the same time, mediating relationships from behind a screen breeds a pervasive sense of isolation.

In the Apple story, the brand cult began offline, with users meeting in real, physical locations to swap programs and ideas. Now, the Apple community is more diffuse, concentrated in online discussion groups and support forums. However, Apple product launches and conferences remain sacred pilgrimages where Apple fans can congregate, camp, and live together for days at a time to revel in the communal joy of witnessing the transcendent moment of the new product launch.

The reverence once reserved for holy relics and liturgy has reemerged in the technology subculture. The shared experience of living in a highly technological era provides a universal ground for a pluralistic society. There may be many different devices, but only one Internet.

Technology has become the new taken-for-granted order that requires our fidelity. Obedience to the new order is expressed in the communication rituals that take place every day in the use of computers, music players, and smartphones — devices that bind individuals together. From the farthest satellite to the nearest cellphone, the mystical body of electricity connects us all. Personal technology has become “the very atmosphere and medium” through which we mediate our daily lives.

But the paradox this media technology presents is the absence of presence. The age of electric media is the age of discarnate man — persons communicating without bodies. From the disembodied voice on the telephone to the faceless email message, electronic communication trades human presence for efficiency.

In order for such a form to become popular, it would take a visionary like Jobs with both technical and humanistic sensibilities; someone to assure the technological faithful that this dramatic change in human relations was a good thing.

The question that remains is whether this mode of perception brings us any closer to recognizing the transcendent hidden at the heart of that which is not digitized or downloaded.

Article from: wired.com

The New Cathedrals: An excerpt from Appletopia

By Brett T. Robinson | Second Nature

The following is an excerpt from Brett T. Robinson’s new book Appletopia: Media Technology and the Religious Imagination of Steve Jobs (Baylor University Press), available starting August 15th.

In 2011 by one estimate the most photographed landmark in New York City was not Rockefeller Center or Times Square; it was the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue. The shimmering glass cube is otherworldly. The $7 million structure stands thirty- two feet high and features a glass spiral staircase wrapped around a glass elevator. A glowing Apple logo floats in the center of the cube. Inside the store, there are no shelves or boxes, just wooden tables with Apple’s glowing products on display. Faithful consumers wander the cavernous interior admiring Apple devices in a virtual “cathedral of consumption.”

In his novel Notre-Dame de Paris, Victor Hugo’s archdeacon looks up at the Notre-Dame Cathedral with a book in his hand and says, “This will kill that. The book will kill the edifice.” Hugo explains the archdeacon’s comment this way:

It was a presentiment that human thought, in changing its form, was about to change its mode of expression; that the dominant idea of each generation would no longer be written with the same matter, and in the same manner; that the book of stone, so solid and so durable, was about to make way for the book of paper, more solid and still more durable.

The cultural authority of the cathedral was giving way to the revolution of ideas unleashed by the printing press and books. Hugo’s parable is instructive for the modern age as well. The authority of the printed page is now giving way to the universality of glass screens.

The transcendent design of the Apple store fits a historical pattern wherein the dominant media technology of an age acquires a sacred status. The baroque design of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the vaulted ceiling of the Long Room in Trinity College Library in Dublin are testaments to the sacred status granted to books as precious vessels of knowledge and cultural patrimony. When books were king, their homes were built in the highest architectural style of the day. Libraries were imagined as sacred spaces because they were instruments for transmitting culture to future generations, promoting community, and organizing chaos.

The Apple Store is a shrine to the modern media technologies that now perform these tasks. Computers and smartphones have become tools for living as they have been integrated into nearly every facet of social and cultural life in the technological society. The durability of stone and paper is giving way to the ephemerality of bits and screens. Book and screen will continue to coexist, but our modes of expression are progressively beginning to favor the screen over the page. Patterns of thinking once routinized by the linear and logical flow of print are becoming more nonlinear and impressionistic by virtue of our heavy interaction with screen media and interactive technology. We are beginning to think differently as a result of the new dominant media technologies.

The Apple Store also resembles La Grande Arche in Paris, a massive cube built to honor the secular humanitarian ideals of postwar France. La Grande Arche is large enough to fit the Notre-Dame Cathedral inside its 348-foot-wide hollow center. La Grande Arche stands in stark contrast to the curvaceous Notre-Dame Cathedral, a baroque building representing old world tradition and fading cultural authority. The modernist cube buttresses the sky, not with spires and gargoyles, but with precise lines and angles, a symbol of rational and disenchanted cultural aspirations. Despite their aesthetic contrast with the cathedrals of old, La Grande Arche and the Apple Store both represent a social order that is deemed inviolable, clothed with an aura of factuality, and vigorously maintained by its adherents. Both monuments to modernism glorify technology and the secular ideals of the age.

Reading the Rhetoric of Technology

The beliefs and values of the technological age are embedded in a web of cultural relationships. The representation and practice of technology are composed of a diffuse set of rituals and rhetoric that resist tidy categorization. Architecture provides a few clues about the beliefs and values of a particular age, but it is in the popular texts of the mass media that a more detailed picture emerges. The images and slogans of technology advertising provide a computer catechism of sorts, teaching the consumer the goods (and evils) of different products and services. Just as the stained glass and statuary of medieval cathedrals educated converts and the illiterate, the iconic images and parables of advertising reveal the virtues of new technology to the buying public. The iconography of the Apple computer company provides a fitting case study for looking at the ways in which technology and the sacred have been conflated in the modern age. The Apple brand is the latest in a long line of American symbols that have captured the national imagination and spawned a “cult” of loyalists. Well before Apple, the most photographed sites in the early twentieth century were places like the Grand Canyon and the Golden Gate Bridge, where tourists united in a collective sense of wonder and nationalism. Standing at the gaping mouth of the Grand Canyon evoked dread and awe, a mix of emotions that made for a sublime encounter.

The sense that the world is charged with grandeur and mystery has largely faded in the wake of a dogmatic deference to rationalism in the modern world. As a result, the world has lost some of its primordial magic. Thus, an electrifying encounter with a technological wonder reinvests the world with a transcendent significance. In a country with divergent religious views, these collective moments of wonder provide an important social bond.

One of America’s great industrial feats, the Golden Gate Bridge, was an answer to the problem of isolation and disconnect. Suspended in the air, the bridge spans an immense physical divide, connecting two cities and millions of people. The bridge is a tremendous feat of art and engineering that fuels a collective faith in our ability to harness technology to overcome the chasms that separate humanity. Communication technologies work in much the same way. The metaphysical space that separates individuals is viewed as an obstacle to more empathic relationships and social cohesion. The imaginary bridges we build with media technologies seem to move us toward a more perfect communion. A noble aspiration to be sure, but it may not be true.

The orientation of personal technology is like its name, highly personal—directed toward the individual rather than the collective. It has led to what the famed sociologist of religion Emile Durkheim called the “cult of the individual.” Durkheim saw the cult of the individual on the horizon as a strong theoretical possibility given the speed with which rationalization was draining religion of its power to provide a meaningful social bond. Transcendence was no longer something to be sought “out there.” The sacred relocated to the subjective experience of the individual. With the advent of personal technologies— symbols of radical individualism realized—the theory appears to have some value.

The cult of Apple is shorthand for the devotion of Apple technology enthusiasts, but their fidelity and fervor point to a more fundamental link between the cult of technology and the cult of the individual. Apple founder Steve Jobs is an allegorical figure for reading the ways in which technology and individual value systems intersect to produce an implicit religion. Technology, like religion, becomes a site where the physical and the metaphysical meet. The promotion of modern technology revives dreams of communion brought on by networked information. The objects that transmit ephemeral bits of culture, promote virtual community, and organize the digital chaos have become sacred objects. Jesus Martín-Barbero puts it this way:

Despite all the promise of modernity to make religion disappear, what has really happened is that religion has modernized itself. . . . What we are witnessing is not the conflict of religion and modernity, but the transformation of modernity into enchantment by linking new communication technologies to the logic of popular religiosity.

The roots of technological faith can be found, ironically enough, in the romanticism of the mid-nineteenth century, a contemplative response to the technological and spiritual changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution. Nineteenth-century American art and poetry echoed a romantic spirit of perfectibility and spiritual encounter between the virgin wilderness and the individual soul. Transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau believed that religious institutions corrupted individual purity, and so they sought a self-reliant spirituality divorced of creeds and dogmas. Modern ideas about monism have their roots in this American romanticism, a spiritual reflection of democratic ideals and the sacred status of the individual in early American political thought. As railroads and telegraph lines transformed the natural landscape, the language of transcendence began to adopt technological metaphors. Emerson saw the new technologies as expressions of a new metaphysical view: “Our civilization and these ideas are reducing the earth to a brain. See how by telegraph and steam the Earth is anthropologized.”

A century later, technology theorists like Teilhard de Chardin would revive Emerson’s vision in the form of the noosphere, an idea that Earth was evolving toward a superconsciousness by virtue of electronic communication. The rhetoric of technology that emerged from the foment of the 1960s counterculture described a new nature that married the metaphysical and the technological. The 1967 poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” by Richard Brautigan combined computers with utopian aspirations: “I like to think / (it has to be!) / of a cybernetic ecology / where we are free of our labors / and joined back to nature, / returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, / and all watched over / by machines of loving grace.” At the heart of the countercultural movement was something vaguely spiritual—a desire for more perfect communion with nature and with one another, a new consciousness.

The coupling of technology and romanticism, science and spirituality, has fostered what American sociologist Philip Rieff has called “the triumph of the therapeutic.” Under these conditions, the moral ideal is a person of leisure, “released by technology from the regimental discipline of work so as to secure his sense of well-being in highly refined alloplastic ways.” The high priests of such an age appear in the form of media icons like Oprah Winfrey, doctors turned mystics like Deepak Chopra, and technology gurus like Steve Jobs. Each of these celebrities supports the cult of the individual by offering psychological and technological salvation to a disenchanted world.

Technology has not always inspired loving grace and flights of spiritual fancy, however. The Luddite movement of the early nineteenth century in England saw textile workers engage in the destruction of mechanized looms in protest of the encroaching automation of labor. The Luddites feared for their livelihood as the Industrial Revolution introduced labor-saving machines that made many workers expendable. Such a dramatic change to a centuries-old way of life was a shock to the economic and cultural system and sowed the seeds for the romantic movement. It was art and poetry that rescued humans from their conflict with machines by invoking an escape into nature. Apple’s Steve Jobs believed that combining art and technology would release people from the old antagonisms. The Apple narrative inspired by Jobs is mythic in its ability to reimagine technology, not as a dehumanizing force, but as something liberating and natural.

Vehicles of Transcendence

The history of Silicon Valley provides a fitting backdrop for reading the American religion of technology. When Steve Jobs set up shop in his parents’ garage to start work on the first Apple computer, a significant cultural shift was under way. Prior to the personal computer, the machine of highest rank in the great chain of automation was the automobile.

At the dawn of the information revolution, it was the car, not the computer, that signaled the coming shift in consciousness that would transform the American landscape. In the early 1900s, the El Camino Real corridor of California was home to dozens of mission churches built by Spanish Franciscan friars to convert and evangelize the Native Americans of the region. The churches were beautiful, built in the Spanish mission style, and they brought a sense of old world mystique to a region that would end up being defined by innovation and technology.

Eventually the glory of the mission churches faded as California became ripe for development. Like those of most states in the early twentieth century, the California landscape was being remapped by the highway system to make way for the automobile. A sampling of tourist photos from the 1920s shows a steady stream of travelers stopping for photo ops in front of the missions with their cars positioned prominently in the foreground. The trip up the California coast, with the infinite expanse of the ocean on one side and portals to the divine on the other, was a motorist’s dream, a way of escaping the everyday. It became one of the most popular automobile tours on the continent.

Tucked into the northern leg of the El Camino Real is the present-day Silicon Valley. Bordered by the Santa Clara Mission, Silicon Valley is sacred ground for those invested in the culture of digital technology. The transformation of El Camino Real from religious-automotive pilgrimage to mecca of modern technology is an allegory for the digital age. It reveals our manic desire for transcendence and all of the means by which we seek it, from religion to cars to computers. Churches, cars, and computers share a secret affinity. They help us escape. The really special ones are works of art. Chartres, Ferrari, and the iPod are all cathedrals—each one transporting us in different ways.

It is fitting then that the Apple computer—the machine that would become the icon of technological sophistication in the information age—was born in a garage. In December 1980, the Apple computer company went public, and the success of the stock offering eclipsed the previous record-setting offering by Ford Motor in 1956. In retrospect, this fact is not surprising given the industrial heights to which Apple would eventually ascend. But Apple and Ford are linked by more than their monetary success and iconic status.

Cars and computers are built to transport the user—one moves the body and the other moves the mind. Both machines changed our relationship to space and time. Automotive transport necessitated the suburb and the superhighway. American maps had to be completely redrawn to record the vast network of highway and byway arteries that became the nation’s circulatory system. Not to be outdone, the growth of electronic communication gave the country a nervous system. Not only could people and materials be transported at high speeds, speech and image could be transmitted at the speed of light. The country was linked by telegraph, telephone, radio, television, and then computer. Private and mobile transcendent experiences were being realized as both cars and computers overcame physical limits.

The communication revolution inspired a slew of sublime rhetoric. In the early days of the personal computer, Nicholas Negroponte of the MIT Media Lab waxed prophetically that our world would be irrevocably changed by the immateriality of bits replacing the materiality of atoms. With the growing popularity of ebooks and the slow death of print newspapers, Negroponte’s predictions echoed the prophecy of Victor Hugo’s archdeacon in Notre-Dame de Paris, “this will kill that.” Negroponte’s rhetoric of digital technology bears the traces of ancient gnostic yearnings to escape the bonds of physical materiality to become one with sacred knowledge, or gnosis.

This pattern of rhetorical transference between the technological and the transcendent has found ample purchase in the Apple story. With Apple and Steve Jobs, the sibling relationship between technology and transcendence is writ large. Apple’s religiosity has been attributed to everything from the company’s “forbidden fruit” logo to the fervent devotion of Apple consumers who make pilgrimages to Apple stores and defend the brand against the heresies of Microsoft. However, the company’s evocative symbols and devoted users are symptomatic of a much deeper transformation at work in the culture.

The Greek word metanoia is helpful in thinking about the transformation in consciousness at work in the digital age. The term is usually associated with religious conversion, but the literal meaning of metanoia (μετάνοια) is “radical change of thought and mind.” In 1997 Steve Jobs staked the future of the beleaguered Apple computer company on a similar idea—a grammatically suspect two-word phrase, “Think Different.” The advertising slogan was an instant hit and became the centerpiece of a promotional campaign for Apple that coincided with the explosive growth of the commercial Internet. The personal computer went from being an object for specialists to a necessary household appliance. The world was beginning to think differently, and Jobs was leading the way. In the spirit of his romantic forebears like Emerson, Jobs imagined the computer as a metaphor for the human mind:

Our minds are sort of electrochemical computers. Your thoughts construct patterns like scaffolding in your mind. You are really etching chemical patterns. In most cases, people get stuck in those patterns, just like grooves in a record, and they never get out of them. It’s a rare person who etches grooves that are other than a specific way of looking at things, a specific way of questioning things. It’s rare that you see an artist in his 30s or 40s able to really contribute something amazing. Of course, there are some people who are innately curious, forever little kids in their awe of life, but they’re rare.

The chemical patterns etched by the habitual use of personal technology are changing the way we think, act, and feel. As a result, cultural practices like religion are beginning to change as well.

When religious ideas were locked away in monasteries and printed on manuscripts, religious authority was centralized. The printing press democratized religious interpretation and put religious texts into the hands of many. The mass production and distribution of theological, philosophical, and scientific ideas was a watershed moment that remapped the intellectual and spiritual landscape of the West. In the age of the personal computer, popular religious positions have become even more diffuse—a symptom of the powerful and personalized technologies we use to communicate.

The computer is more decentralized than are printed books. Tim Berners-Lee, lead architect of the World Wide Web, noted the parallels between his Unitarian Universalist faith and the decentralized architecture of the web, designed to encourage tolerance and a mutual search for truth. The ethic of the Internet age is rooted in free expression, a breakdown of hierarchy, a sense of individual empowerment, and a distrust of central authority. Each of these developments poses a threat to traditional religious institutions. It should be no surprise that religious participation has faltered rather than flourished since the birth of the television and the computer. This is not to say that technology is the only factor in the erosion of religious influence, but the correspondence of the two trends is more than coincidence.

The void left by fading religious authorities and the ethic instilled by technology use may favor a more libertarian approach to spiritu- ality and belief, but the desire for transcendence persists. When the shared sense of transcendence recedes from the wonders of nature and the baroque cathedrals of religion, enchantment is sought elsewhere. Digital images of the sublime, from the Grand Canyon to the outer reaches of the cosmos, now live on computer desktops and screen savers as constant reminders of the human desire to see beyond the blandness of routinized work. The computer provides a mode of escape and an invitation to dwell in an alternative universe of imagery and information.

Media Metaphors and Religious Rhetoric

Education and catechism in the technological religion extend into all areas of cultural life. Children are introduced to communication technologies in the home at a very early age. The millennia it took for man to move from oral communication to print communication to electronic communication have been condensed to a few years for the young initiate. Once the initiate is in school, the educational environment provides further training in computers and media literacy. By high school, many children are outfitted with laptops purchased by the school. The ritual use of computers and cell phones by young people places them in “imagined communities” where relationships consist of text messaging, email, and sharing other bits of media.

The use of cell phones, laptops, and tablets has skyrocketed over the past decade, and the trends show no signs of slowing down. Americans spend between eight and nine hours a day in front of some type of screen. While the television still accounts for the bulk of screen time among Americans, the computer and mobile devices are quickly encroaching. Among eighteen- to forty-four-year-olds, the combined time spent with computers and mobile devices is nearly equal to television screen time. As screen time increases, the character of social and cultural life changes.

A Latin phrase is frequently repeated in the Catholic Church: lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi, which can be translated, “how we worship reflects what we believe and determines how we will live.” In the age of screen worship, media technology has become a determinant of contemplative habits (or lack thereof). Apple’s Steve Jobs was fond of the Hindu saying, “In the first 30 years of your life, you make your habits. For the last 30 years of your life, your habits make you.” Jobs had it printed on invitations to his thirtieth birthday party. The phrase was prescient. Over the next two decades, the technology products Apple created became a global obsession. Jobs’ habits changed the world.

The word “habit” comes from the religious apparel worn by clerical orders of monks and nuns. It also means a “customary practice.” The iPods worn by millions of Apple devotees are both apparel and habitual practice. The popularity of listening to digital music, reading electronic books, and browsing the Internet on cell phones is due in large part to Jobs’ inspiration.

Apple devices encourage self-expression by inviting spontaneous creativity and personalization. The ads for the Apple iPod are icons of ecstatic self-expression, as silhouetted dancers let loose in fits of choreographed glee, their bodies coordinated with the rhythm of the music supplied by their iPod devices. The faceless shadows that float on psychedelic backgrounds in the iPod ads connote a spiritual happening. The music affects both body and soul. The ability of the iPod ads to evoke religious comparison is a product of their highly metaphorical presentation.

Religious communication uses metaphorical language because it proposes realities that cannot be grasped directly. The invisible workings of the metaphysical realm are understood in relation to something sensible and concrete. Religion is communicated through stories, symbols, art, and analogies. The parables in the gospel are common tales of farmers, day laborers, and landowners. Images of fruitful seeds, just wages, and merciful fathers reveal facets of an infinite God to the finite mind. The Buddhist concept of dukkha (suffering) is a metaphorical term that translates as “bad wheel.” The Buddha compared suffering to the bad wheel of an oxcart that makes for an unsteady and uncomfortable ride. The use of metaphor in religious rhetoric makes the metaphysical sensible.

The rhetoric of technology resembles religion in its need for metaphors to make the unknown sensible. It is why the steam engine was first explained in terms of horsepower rather than a physics equation. Thanks to artistic engineers like Jobs, computers are filled with easy-to-understand metaphors: folders, desktops, icons, and memory to name just a few. Part of Jobs’ genius was finding the metaphors that resonated with the uninitiated user. While a term like subdirectory meant very little to the average user, putting a file in a folder made perfect sense. Making the computer interface visual and image-based rather than text-based made the experience of personal computing accessible to those who were not computer literate.

The education of the illiterate through the use of metaphors and visual icons bears a resemblance to the experience of medieval churchgoers who relied on iconography, stained glass, and cathedral architecture to provide instruction on the core tenets of the faith. Italian cultural critic and semiotician Umberto Eco made the connection between the metaphors of religion and technology in a famous essay in which he described “a new underground religious war which is modifying the modern world.” Eco’s tongue-in-cheek metaphor goes like this: The Apple Macintosh computer is Catholic and Microsoft Windows/DOS is Protestant. Macintosh is Catholic because it is “counter-reformist and has been influenced by the ratio studiorum of the Jesuits. It is cheerful, friendly, conciliatory; it tells the faithful how they must proceed step by step to reach—if not the kingdom of Heaven—the moment in which their document is printed. It is catechistic: The essence of revelation is dealt with via simple formulae and sumptuous icons. Everyone has a right to salvation.”

The DOS machine is Protestant because “it allows free interpretation of scripture, demands difficult personal decisions, imposes a subtle hermeneutics upon the user, and takes for granted the idea that not all can achieve salvation. To make the system work you need to interpret the program yourself: Far away from the baroque community of revelers, the user is closed within the loneliness of his own inner torment.” His analysis also includes the improvements made by Microsoft to upgrade DOS to Windows. Eco notes, “Windows represents an Anglican-style schism, big ceremonies in the cathedral, but there is always the possibility of a return to DOS to change things in accordance with bizarre decisions: When it comes down to it, you can decide to ordain women and gays if you want to.”

Eco’s satirical approach reveals the compatibility of religious and technological metaphors. This was not lost on Steve Jobs, who approached new technology with the zeal of a prophet. Undeterred by social critics who saw computers as an expression of dehumanization in the modern age, Jobs saw creativity and life in the cold, beige machines that were taking over corporate cubicles and military installations. Within a decade of starting the Apple computer company in his garage, Steve Jobs staged an ideological battle with computer manufacturing giant IBM over what it meant to be human in the age of machines.

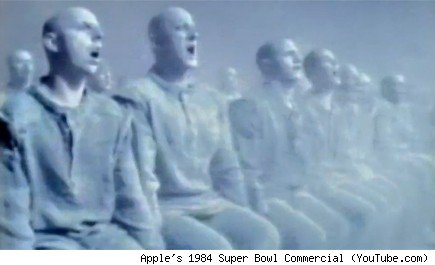

Inspired by a sense of spiritual purpose, Steve Jobs warned that an unchallenged IBM would usher in a dark age in which bleak boxes of microchips would turn workers into mindless drones. Jobs flipped the script by imagining computers as mystical tools for unleashing human creative potential. Jobs’ vision of machines as spiritual liberators was enshrined in the famous 1984 advertisement depicting IBM as George Orwell’s Big Brother and Apple as the rebellious hero smashing the shibboleths of the IBM computer culture.

The story of our love/hate relationship with technology is best told by the artists. Man and technology are two actors involved in a timeless story about the response of the creator to the created. This is the stuff of myth, poetry, legend, and religion. Adam and Eve, Prometheus, and Frankenstein’s monster all speak to the dreadful and intoxicating proposition of playing God. And it is the sense of dread and overwhelming mystery that evokes the sublime. The sublime can be both a religious sensation and a technological one. In the techno- logical age, it is not just the poets and painters who present the transcendent but the engineers and programmers as well.

Advertising has been dubbed the “official art” of capitalist society, and rightly so. Advertising is more than persuasive rhetoric; it is an aesthetic encounter. The mode of persuasion in advertising is not always rational; it is highly emotive. Evocative images, music, and the physical design and contours of a product are seductive; they call upon our sensuality. In the modern cultural climate, where product art is more influential and pervasive than fine art, the proliferation of values and taste changes. Fine art represents human longing by depicting what we believe is true and good and beautiful. In the world of product art we receive a distorted view of the true, the good, and the beautiful. We are shown material goods that are beautified, and we are told that the promises they make are true.

Our ideas about the true, the good, and the beautiful come from religious belief. If advertising parodies such metaphysical ideals, then it is also taking a swipe at religion. Such parody is evident in everything from Angel Soft toilet paper to Miracle Whip. The fallout from this semantic hijacking changes the way religion is perceived. Religious traditions are raided for symbols and narratives to enhance the appeal of commodities. When those symbols are abstracted from their traditions and used for other purposes, they are drained of their primordial potency. In certain cases, the products and brands themselves take on a religious significance.

The reciprocal use of technological and religious metaphor has led to some imaginative rhetoric over the centuries. Steve Jobs and the Apple computer company embody the blending of technology and religion metaphors remarkably well; they offer a curious mix of the technical and the transcendental, the mechanical and the mystical, the technological and the theological. From Jobs’ esoteric Buddhism to the Apple consumers who proudly declare their membership in the Apple cult, the commingling of religion and technology in the Apple story is a reflection of a persistent and fascinating cultural preoccupation. A society’s most popular technologies provide the all-important metaphors for articulating spiritual concerns. As such, Steve Jobs and the Apple computer company provide hieroglyphs for understanding the sibling relationship between technology and the sacred in the computer age.

The advertisements for the Apple computer company are emblems of a culture that has adopted technology as a de facto religion, a religion that celebrates the cult of the individual. Media devices are the means by which we communalize our concerns and ritualize the practice of self-divinization by procuring the powers of omniscience and omnipresence granted by a global communication network. Personal computers, music players, and cell phones fashion us votaries of the digital age, and Apple has imagined our technological conversion in compelling ways. Apple’s advertisements provide a rich visual allegory for reading the transference of spiritual and technological desire in the digital age.

Article from: secondnaturejournal.com

Click here to watch the Red Ice TV analysis on the occult origins of the Apple logo :

http://youtu.be/wb1oi3Ucje0?t=13m52s

Or watch the full episode:

Red Ice TV: Symbolism of Logos (full episode)

From LATimes.com:

An ad for the first iPhone played off the Bible’s "Doubting Thomas" story.

"The enlightenment was an element, Robinson says, of Apple’s famous "1984" Super Bowl commercial, in which a female runner throws a hammer that smashes an Orwellian figurehead on a giant screen. Instead of a fiery explosion, the drones looking on are bathed in bright light as they seem to awaken and stir."

"Apple even began to employ "evangelists" to spread the word about its products to developers and customers. And the return of Jobs later to Apple fed the religious allusions (i.e., Apple would be "resurrected" or "rise from the dead.") "