In Brookhaven Collider, Scientists Briefly Break a Law of Nature

Source: nytimes.com

Physicists said Monday that they had whacked a tiny region of space with enough energy to briefly distort the laws of physics, providing the first laboratory demonstration of the kind of process that scientists suspect has shaped cosmic history.The blow was delivered in the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, or RHIC, at the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, where, since 2000, physicists have been accelerating gold nuclei around a 2.4-mile underground ring to 99.995 percent of the speed of light and then colliding them in an effort to melt protons and neutrons and free their constituents — quarks and gluons. The goal has been a state of matter called a quark-gluon plasma, which theorists believe existed when the universe was only a microsecond old.

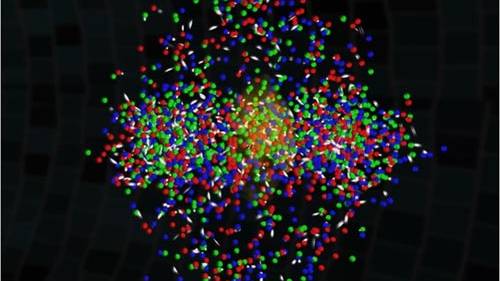

HOT! A computer rendition of 4-trillion-degree Celsius quark-gluon plasma created in a demonstration of what scientists suspect shaped cosmic history.

The departure from normal physics manifested itself in the apparent ability of the briefly freed quarks to tell right from left. That breaks one of the fundamental laws of nature, known as parity, which requires that the laws of physics remain unchanged if we view nature in a mirror.

This happened in bubbles smaller than the nucleus of an atom, which lasted only a billionth of a billionth of a billionth of a second. But in these bubbles were “hints of profound physics,” in the words of Steven Vigdor, associate director for nuclear and particle physics at Brookhaven. Very similar symmetry-breaking bubbles, at an earlier period in the universe, are believed to have been responsible for breaking the balance between matter and its opposite antimatter and leaving the universe with a preponderance of matter.

Video from: YouTube.com

“We now have a hook” into how these processes occur, Dr. Vigdor said, adding in an e-mail message, “IF the interpretation of the RHIC results turns out to be correct.” Other physicists said the results were an important window into the complicated dynamics of quarks, which goes by the somewhat whimsical name of Quantum Chromo Dynamics.

Frank Wilczek, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who won the Nobel Prize for work on the theory of quarks, called the new results “interesting and surprising,” and said understanding them would help understand the behavior of quarks in unusual circumstances.

“It is comparable, I suppose, to understanding better how galaxies form, or astrophysical black holes,” he said.

The Brookhaven scientists and their colleagues discussed their latest results from RHIC in talks and a news conference at a meeting of the American Physical Society Monday in Washington, and in a pair of papers submitted to Physical Review Letters. “This is a view of what the world was like at 2 microseconds,” said Jack Sandweiss of Yale, a member of the Brookhaven team, calling it, “a seething cauldron.”

Among other things, the group announced it had succeeded in measuring the temperature of the quark-gluon plasma as 4 trillion degrees Celsius, “by far the hottest matter ever made,” Dr. Vigdor said. That is 250,000 times hotter than the center of the Sun and well above the temperature at which theorists calculate that protons and neutrons should melt, but the quark-gluon plasma does not act the way theorists had predicted.

Instead of behaving like a perfect gas, in which every quark goes its own way independent of the others, the plasma seemed to act like a liquid. “It was a very big surprise,” Dr. Vigdor said, when it was discovered in 2005. Since then, however, theorists have revisited their calculations and found that the quark soup can be either a liquid or a gas, depending on the temperature, he explained. “This is not your father’s quark-gluon plasma,” said Barbara V. Jacak, of the State University at Stony Brook, speaking for the team that made the new measurements.

It is now thought that the plasma would have to be a million times more energetic to become a perfect gas. That is beyond the reach of any conceivable laboratory experiment, but the experiments colliding lead nuclei in the Large Hadron Collider outside Geneva next winter should reach energies high enough to see some evolution from a liquid to a gas.

Parity, the idea that the laws of physics are the same when left and right are switched, as in a mirror reflection, is one of the most fundamental symmetries of space-time as we know it. Physicists were surprised to discover in 1956, however, that parity is not obeyed by all the laws of nature after all. The universe is slightly lopsided in this regard. The so-called weak force, which governs some radioactive decays, seems to be left-handed, causing neutrinos, the ghostlike elementary particles that are governed by that force, to spin clockwise, when viewed oncoming, but never counterclockwise.

Under normal conditions, the laws of quark behavior observe the principle of mirror symmetry, but Dmitri Kharzeev of Brookhaven, a longtime student of symmetry changes in the universe, had suggested in 1998 that those laws might change under the very abnormal conditions in the RHIC fireball. Conditions in that fireball are such that a cube with sides about one quarter the thickness of a human hair could contain the total amount of energy consumed in the United States in a year.

All this energy, he said, could put a twist in the gluon force fields, which give quarks their marching orders. There can be left-hand twists and right-hand twists, he explained, resulting in space within each little bubble getting a local direction.

What makes the violation of mirror symmetry observable in the collider is the combination of this corkscrewed space with a magnetic field, produced by the charged gold ions blasting at one another. The quarks were then drawn one way or the other along the magnetic field, depending on their electrical charges.

The magnetic fields produced by the collisions are the most intense ever observed, roughly 100 million billion gauss, Dr. Sandweiss said.

The directions of the magnetic field and of the corkscrew effect can be different in every bubble, the presumed parity violations can only be studied statistically, averaged over 14 million bubble events. In each of them, the mirror symmetry could be broken in a different direction, Dr. Sandweiss explained, but the effect would always be the same, with positive quarks going one way and negative ones the other. That is what was recorded in RHIC’s STAR detector (STAR being short for Solenoidal Tracker at RHIC) by Dr. Sandweiss and his colleagues. Dr. Sandweiss cautioned that it was still possible that some other effect could be mimicking the parity violation, and he d held off publication of the results for a year, trying unsuccessfully to find one. So they decided, he said, that it was worthy of discussion.

One test of the result, he said, would be to run RHIC at a lower energy and see if the effect went away when there was not enough oomph in the beam to distort space-time. The idea of parity might seem like a very abstract and mathematical concept, but it affects our chemistry and biology. It is not only neutrinos that are skewed. So are many of the molecules of life, including proteins, which are left-handed, and sugars, which are right-handed.

The chirality, or handedness, of molecules prevents certain reactions from taking place in chemistry and biophysics, Dr. Sandweiss noted, and affects what we can digest.

Physicists suspect that the left-handedness of neutrinos might have contributed to the most lopsided feature of the universe of all, the fact that it is composed of matter and not antimatter, even though the present-day laws do not discriminate. The amount of parity violation that physicists have measured in experiments, however, is not enough to explain how the universe got so unbalanced today. We like symmetry, Dr. Kharzeev, of Brookhaven, noted, but if the symmetry between matter and antimatter had not been broken long ago, “the universe would be a very desolate place.”

The new measurement from the quark plasma does not explain the antimatter problem either, Dr. Sandweiss said, but it helps show how departures from symmetry can appear in bubbles like the ones in RHIC in the course of cosmic evolution. Scientists think that the laws of physics went through a series of changes, or “phase transitions,” like water freezing to ice, as the universe cooled during the stupendously hot early moments of the Big Bang. Symmetry-violating bubbles like those of RHIC are more likely to form during these cosmic changeovers. “If you learn more about it from this experiment, we could then illuminate the process that gives rise to these bubbles,” Dr. Sandweiss said.

Dr. Vigdor said: “A lot of physics sounds like science fiction. There is a lot of speculation on what happened in the early universe. The amazing thing is that we have this chance to test any of this.”

Article from: NYTimes.com

RedIce Radio:

Holger Bech Nielsen - CERN & the Large Hadron Collider ’Being Sabotaged from the Future’

Holger Bech Nielsen - Quantum Theory, String Theory, Time Travel, Higgs Boson & "god"

William Henry - The Apotheosis is at Hand, NWO, COP15, Norway Blue Spiral & Stargates

Nassim Haramein - The Resonance Project