Luddites: They raged against the machine and lost

Source: missoulian.com

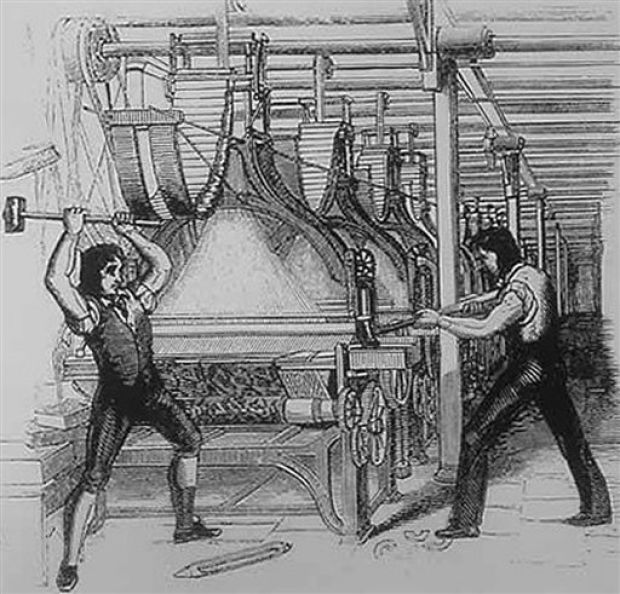

Their name is synonymous with futile attempts to roll back technology _ and with fuddy-duddies who can’t figure out how to use the iPhone.The Luddites were British textile artisans who 200 years ago smashed the mechanized looms they thought threatened their jobs.

They weren’t the first to attack machines. They are named after a man who probably didn’t exist. And their grievances weren’t even with the looms themselves; they were enraged at the business owners who hired unskilled laborers to use the machines and turn out shoddy products that ruined the artisans’ reputation for quality.

Their movement began in economic misery. Britain’s long war with Napoleon had taken a toll. The economy was squeezed by a French blockade that cut exports and sent food prices soaring. Their livelihoods threatened by low-wage labor, the artisans began demonstrating around Nottingham in 1811.

The protests _ and the machine-busting _ spread across a swath of central England. Some of the Luddites swung hammers forged by a blacksmith named Enoch Taylor, who also made machinery for their adversaries, mill owners. "Enoch made them," the Luddites would say. "So Enoch shall break them."

An outraged Parliament passed a law imposing the death penalty on machine wreckers _ a draconian move opposed by the poet Lord Byron, who said the Luddites deserved pity, not punishment.

This publicly distributed illustration from 1812 shows frame-breakers, or Luddites, smashing a loom. The Luddites were British textile artisans who 200 years ago smashed the mechanized looms they thought threatened their jobs. Machine-breaking was criminalized by the Parliament of the United Kingdom as early as 1721, but the Frame-Breaking Act 1812 made the death penalty available.

The government sent soldiers to restore order. At one point, the late historian Eric Hobsbawm has written, Britain had more troops deployed against the Luddites than (they) it had fighting Napoleon in Spain and Portugal.

Several Luddites were killed in clashes with troops. Others were hanged. By the end of 1814, the Luddite protests were over. The Industrial Revolution rolled on, replacing artisans with factory workers.

But the Luddites had made quite an impression. They had a talent for showmanship. They wrote mischievous, official-sounding decrees addressed from Sherwood Forest, an attempt to claim the legacy of Robin Hood. They marched through the streets dressed as women, claiming to be "General Ludd’s wives."

But there was no General Ludd.

Historians aren’t sure where the name came from. Years earlier, by one account, a young apprentice named Ned Ludd had smashed the machine he was working on after being punished by his master. But in other accounts, the boy’s name is Ludlum. And in his book on the Luddites, "Rebels Against the Future," author Kirkpatrick Sale suggests the term may have come from an expression used then in parts of England _ "sent all of a lud," which meant ruined.

Whatever its origins, the name stuck.

The Luddite label has been applied to everyone from anti-technology extremists _ such as the "Unabomber," Ted Kaczynski _ to those who merely struggle with technology or don’t want to bother with it. "I’m a Luddite," pop star Elton John told Britain’s The Telegraph newspaper in 2011. "I don’t have a phone. I don’t have a computer. I don’t have an iPad. And I don’t have an iPod."

Sometimes the Luddite label serves as an all-purpose epithet for someone who’s not with the times. When University of Chicago economist Raghuram Rajan raised unwelcome questions about the stability of the world financial system in 2005, for instance, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers dismissed his argument as "slightly Luddite."

Three years later, investment bank Lehman Bros. collapsed, and the global economy toppled into the deepest recession since the 1930s.

For once, at least, the Luddite was right.

Article from: missoulian.com