Maryland's Prometheus

Source: living.scotsman.com

Ed Comment: For those who have seen the Red Ice Creations Short Film Longevity & The Grail, this article from The Scotsman is screaming with absolutely incredible symbolic information about Craig J Venter, and confirms a lot of the symbolic ideas we elaborated on in the episode.

Few Branches of science are as emotive as genetics, and few scientists have stoked the flames of debate quite like Craig Venter. For a decade or more, the American geneticist has regularly acted as a kind of lightning rod for the hopes, fears and arguments that surround research into the building blocks of life, especially human life.

Venter, with his corporate backers, was the man who competed, and tied, with the publicly funded US effort to map the human genome seven years ago, which earned him plenty of plaudits but also the moniker "Darth Venter" and reportedly comparisons to Hitler by double-helix pioneer and Nobel laureate James Watson. It turn-ed out the DNA Venter sequenced was mainly his own, and just last month he followed this up with the publication of his full six-billion letter genetic code, a world first. Now he says he's on the verge of creating a brand new life form in his Maryland lab using synthesised genes, and has applied for a patent for the manufactured bacterium. The critics are already squaring off: one Cambridge biochemist has dismissed the science as facile reductionism, while a Canadian bioethics group says no patent should be granted, warning: "for the first time God has competition".

Judging by his autobiography, Venter is the kind of person who would register the compliment in this last remark but not much else. His view of himself may not be God-like, but it's more than a little Promethean. As he takes us on a blow-by-blow journey through a frankly astonishing career in the intense and competitive world of bleeding-edge biotechnology, what emerges is a rather simple heroic narrative: Venter's Venter is a classic American individualist, the underdog who beat the odds, a flawed idealist in the service of humanity.

Born in 1946, his story begins in the lower middle class outskirts of San Francisco, where he was a smart, but rebellious and underachieving youth, perhaps in part due to attention deficit disorder. The epiphany came in Vietnam. After five months as a conscript in a frontline medical unit, he swam into the ocean at night to get away from "bullshit, the madness, the horror", only to be prodded by a shark and the sudden realisation that he desperately wanted to live. He turned back, and ultimately the hundreds of wounded soldiers he dealt with, plus a stint at an infectious diseases clinic, transformed him "from a young man without purpose to one compelled to understand the very essence of life".

Ed Note: In another article it says that Craig J Venter encountered a snake while swimming out to sea... that's a bit more symbolically interesting!

I don't know if it's "The Scotsman" or the following paragraph from "The Times" that has the correct story.

Born in 1946, he was a blond, surfing Californian kid, successful with girls, mediocre at lessons. When he was drafted, he was found to have an IQ of 142, and trained as a medic. In Vietnam, he was so overwhelmed by the suffering that he decided to commit suicide by swimming out to sea. But he was attacked by a sea snake and changed his mind. Clutching the snake, he swam back to shore and killed it. Its skin now hangs in his office.You can read more of The Times article: here

So Prometheus (The Light Bringer / the Light of the World) from Maryland (Mary Land) is killing a snake? Does this echo a religious motif or what?

Madonna and Child with St Anne (Madonna dei Palafrenieri)

By Caravaggio, 1605-1606

From wikipedia: The allegory, at its core, is simple. The Virgin with the aid of her son, whom she holds, tramples on a serpent, the emblem of evil or original sin.

Back home, Venter went to university and quickly got a foot on the academic ladder by publishing fresh research on how adrenaline acts in the human body, ideas that he followed up for the next decade. It was the hunt for the adrenaline receptor gene in the early 1980s that launched him on the road towards the human genome - a vast, big-budget series of labours that gambled on new technology and new variations of "shotgun sequencing", which involves reading bits of cut-up DNA and reassembling the jigsaw later with computers.

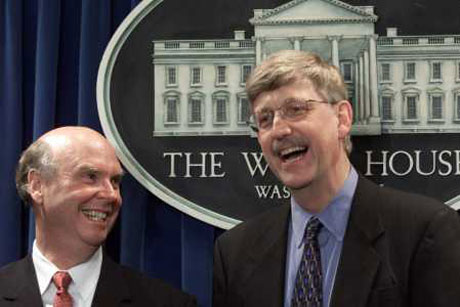

After first mapping the smallpox genome, Venter, to prove his methods worked, published, in 1995, the first genetic blueprint of a living organism, the Haemophilus influenzae bug (unrelated to the common flu), with more microbial genomes to follow. By now at the head of his own company, Celera, "a scientific Camelot" (Hello! Grail reference!), he went into overdrive, getting into a race with the $3bn Human Genome Project that proved highly acrimonious, not least because Venter promised the results for a fraction of the cost. There was only a brief gesture of private-public togetherness when all gathered at the White House in June 2000 to hear Bill Clinton announce that the sequencing of the genome was more or less complete.

"We were hot, the science was hot," Venter enthuses, and he does get across the sheer exhilaration of discovery, even if the lay reader might not grasp all the technical detail. What he also gets across is what can happen when research scientists get into bed with the biotech industry, which, like any industry, is primarily concerned with its bottom line. Thus, along with the breast beating (often justified but a little irritating) and the tendency to quote positive newspaper headlines (just irritating), Venter is out to settle scores and defend his good intentions.

In his account, broad gene patenting, which he now opposes, was first pushed on him by the US government's National Institute of Health, the place where his DNA sequencing started to take off. But amid a fog of scientific rivalries, James Watson used this to turn Venter personally into "the poster boy for commercialisation of research, a scapegoat and a villain, all rolled into one", stitching him up at a Senate hearing in 1991.

Yet Venter did go private shortly afterwards, to get away from the "lumbering government bureaucracy and the pettiness of the politics of science". About this, he airily pleads guilty to wanting to have his cake and eat it, to have the recognition of his peers while looking after his commercial partners. "My critics dwelled upon how I was only in research for the money," he writes. "They got it backward: I was interested in the money only to have the freedom to do my research". But at the same time, Venter found himself in a constant struggle with the money men over the restriction of data, for which he knew he was loathed by swathes of the genome community. He believes the stress of it was responsible for a colonic disease and the consequent removal of part of his intestine. When he finally freed himself from his first set of backers - who were all about "greed and power, not health" - and formed Celera, he deposited all his previous results in a public database.

What we have is a self-portrait of a man driven by ambition into conflict with himself and with those around him - his obsession with the genome and getting the financing to map it even cost him his long second marriage. Venter is brave to lay all of this out so candidly, and indeed, to reveal himself as a person who always seems to need someone or something to kick against as he ruggedly forges his way onwards and upwards. Perhaps inadvertently, he provides the perfect example of this when he describes a boat race - he's a yachting fanatic - from New York to Falmouth that he entered in 1997, as his career was moving in to top gear - he won the race in 15 days, overcoming both difficult Atlantic seas and a sniffy yacht-racing establishment. The heroic underdog comes through once again.

Meanwhile, the issues that Venter's story bring into relief loom larger than ever. According to a study that is already two years old, one-fifth of known human genes, about 4,400, have been patented, more than 60 per cent by private firms. Since the way most genes work is still uncharted, many scientists fear the rush to patent will stymie research. It also seems likely that as scientific understanding progresses, there will be more conflicts of the type that saw the EU revoke a patent on a breast-cancer gene three years ago, to cut the cost of screening.

Ultimately more worrying is that genetics may offer opportunities for easy discrimination. Venter speaks out strongly here against genetic determinism, and says it was part of the reason he put his own genome - which suggests an increased risk of Alzheimer's and heart disease - in the public domain. "You cannot define a human life or any life based on DNA alone," he writes. "Without understanding the environment in which cells or species exist, life cannot be understood." In Britain, John Sulston, acting chair of the Human Genetics Commission (and coincidentally one of Venter's old rivals) wants genetic discrimination at work and in insurance outlawed. As for actual gene manipulation, it's a distant prospect, but there are those who would relish some form of neo-eugenics. Watson himself has controversially talked about ridding society of its "stupidest" 10 per cent, and he got himself in the news again last week after suggesting that Africans were genetically inferior to white westerners. We can leave race out of it, but is there anyone confident enough to rule out the possibility that today's economically underprivileged could, in a piecemeal fashion, become tomorrow's genetic underclass?

For the moment Venter has left human DNA behind. Today's mission, now directed by the J Craig Venter Institute, is to save the world. The new life form he aims to create is an attempt to find the minimal collection of genes required for a living organism. Why? Because he wants to design one that can suck greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere, or produce an endless supply of bio fuels.

Outstanding ethical issues aside, if Venter succeeds his critics may, for once, be at a loss for words.

Watch the Longevtiy & The Grail Promo

Article from: http://living.scotsman.com/books.cfm?id=1712862007