Masonic Lodges Open Those Mysterious Doors

Source: nytimes.com

A replica of a mildewed 14th- century scroll has been unfurled and displayed at a library in New York. An eagle clutching arrows and ribbons, on a tattered flag made around 1803, has just been restored and framed for viewing at a Philadelphia museum. Near Boston a museum exhibition decodes cryptic symbols like compasses and columns embossed on metal badges and embroidered onto aprons.

That the public is now being enthusiastically shown these previously hidden-away items indicates that Freemasons in America are trying to shed their reclusive, somewhat fusty image. Tour guides at the groups’ lavishly ornamented lodges, mostly built around 1900, are explaining ceremonial rituals in newly restored rooms with murals of ancient builders polishing stones and vitrines full of gold pendants and domed velvet hats.

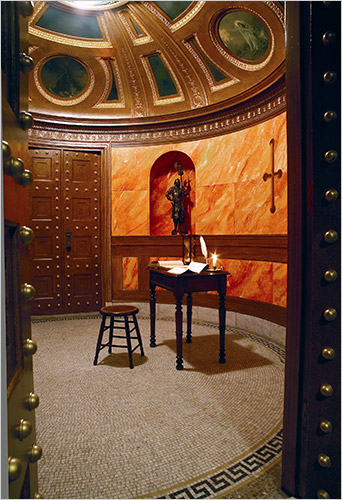

Now open to the public, the Chamber of Reflection at the Grand Lodge of Masons of Massachusetts, in Boston. Roger Appell/ Grand Lodge of Massachusetts

“We’re trying to help more people hear our story accurately,” said H. Robert Huke, the communications and development director at the Grand Lodge of Masons of Massachusetts, an 1899 state headquarters in downtown Boston covered in sunburst mosaics. When curiosity seekers get to visit Masonic rooms, he added, “they’re less inclined to think we’re trying to control the world and run the banks.”

Freemasons have been portrayed as conspirators in books like Dan Brown’s “Da Vinci Code” and “The Lost Symbol” (due on Sept. 15) and the “National Treasure” movies starring Nicolas Cage. The truth is less entertaining. Founded around 1600 by British stonemasons, the men-only clubs hold closed sessions mainly to teach ecumenical ethics codes and raise money for charity, especially medical care. On their lodge walls and ceremonial clothing, motifs like eyes, beehives and drafting tools refer to virtues like steadfastness, tolerance and industriousness.

As befits an organization set up by builders, the clubs are now spending millions of dollars repairing their architectural splendors. In the last year the Masons in Boston have restored spaces with gilded, coffered ceilings and imposing names like the Chamber of Reflection and Corinthian Hall.

Last fall the main Philadelphia lodge finished redoing its turreted roof, granite exterior, murals of woodlands and an early 1800s flag. The public now enters via the forbidding 17-foot-tall front doorway, formerly accessible to Freemasons only.

In Washington, Masons are overhauling a pyramidal building based on a Greek mausoleum while planning new galleries for videos and displays of “magnificent regalia,” said Arturo de Hoyos, the group’s archivist. He added, “We want to create a coherent presentation on the origins, development and meaning of Freemasonry.”

As curators bring dusty Masonic objects out of storage and acquire new ones, docents are explaining the symbolism to noninitiates, men and women. (Many lodges now have Web sites announcing tour times and some even offer 360-degree views of the interiors.)

At 71 West 23rd Street in Manhattan, officially called the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York, guides now point out the library’s modern copy of a 1308 transcript from papal heresy interrogations of Knights Templar and to a meeting hall’s portrait of a black man in a fur anorak; he’s Matthew Henson, a Freemason, who accompanied Robert Peary on Arctic expeditions.

The Massachusetts Masons own so many artifacts — about 12,000 at last count — that in the last few years they have lent them to the National Heritage Museum in Lexington, Mass. Through Oct. 25 highlights of the lodge treasury are on view at the museum, including a gold urn and silver ladle by Paul Revere. (In the 1790s, he was the group’s most worshipful grand master.) A show opening Sept. 26 will survey anti-Masonic screeds from the last three centuries that accuse members of plotting against royalty or propping up Communism.

“There will always be people who are suspicious” of Freemasons, Mr. de Hoyos said. “But even if we’re mentioned negatively, that gets people asking questions and coming here. It opens doors.”

GRANT WOOD RELICS

Ninety feet of cornfield murals, which Grant Wood painted at an Iowa hotel ballroom in 1927, are being reassembled. Torn out and scattered in 1970, the canvas vistas of bundled cornstalks, wooden fences and farm buildings have been found in attics and offices all over the state.

“This is like putting Humpty Dumpty back together again,” said Laural Ronk, the executive director of the Bluffs Arts Council in Council Bluffs, where the former Hotel Chieftain, now converted into apartments for the elderly, contained the pastoral ballroom. The arts council has located 29 mural segments so far; the nine that it has acquired are being sent for treatment to the Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center, a division of the Nebraska State Historical Society in Omaha. Reattaching loose paint and preparing the canvases for storage, among other repairs, will cost about $120,000.

A few mural sections are temporarily stored at Ms. Ronk’s home and her office. “One is folded and shrink-wrapped, and we’re afraid to even open it,” she said. “I’ve been collecting any flakes that fall off.”

The arts council has been contacting government officials about potential display spaces for the restored landscape. “This could be an icon for our community, and a tourism draw,” she said. “We’d like to be added to the Grant Wood trail.”

WHITE HOUSE HISTORY

Few parts of the White House interior actually date back to its early 19th century origins. Harry S. Truman’s chief architect for renovations, Lorenzo S. Winslow, gutted the place, reinforced it with concrete and then installed new crown moldings, fluted columns and carved eagles, stars and shields. The house turned into an “eerie modernized avatar” of its former self, Ulysses Grant Dietz and Sam Watters write in a history due next month, “Dream House: The White House as an American Home” (Acanthus Press).

Evidence of Winslow’s heavy-handed approach will be for sale on Thursday at James D. Julia Auctioneers in Fairfield, Me. One lot, estimated to bring $12,000 to $16,000, contains 23 drawings from Winslow’s office for new reception rooms, staircases, corridors and family gathering spaces. Owned by an unidentified consignor in Maine, the pages are three or four feet long, and their ripped edges and handwritten measurement notations suggest they were used at the construction site.

William G. Allman, the White House curator, said workmen in the 1950s probably took home many such drawings as souvenirs. “I don’t think,” he said, “there was an official policy, the kind there would be from the Secret Service today, that something like this could not leave the premises.”

Article from: NYTimes.com

Raliegh Lodge 770, Memphis, Tennessee

Item in collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts. Photograph by David Bohl.

Michael Tsarion - The Brotherhood of Death - Part One - Masonry & Judaism

Gary A. David - Masonic Phoenix & the 33rd Parallel (Subscription)

Wayne Herschel - The Forbidden Star Map & Masonic Tracing Board

Wayne Herschel - The Hidden Records

Wayne Herschel - The Hidden Records & Freemasonry (Subscription)

Jake Kotze - WTC, Freedom Tower, Octagons & Symbolism (Subscription)

Philp Willan - The Last Supper, Vatican, Masons, P2, Mafia & the Murder of Roberto Calvi

Peter Levenda - Sinister Forces

Peter Levenda - Sinister Forces Continued (Subscription)

Philip Coppens - The Stargate Conundrum & The Nine (Subscription)

Jay Weidner - Future, Freemasonry, Franklin & Films

Jay Weidner - Magic Square, Numerology, Geometry & Gematria (Subscription)

Frank Albo - Freemasonry & Western Hermeticism