Mr Faber’s Amazing Talking Head

Source: laputanlogic.com

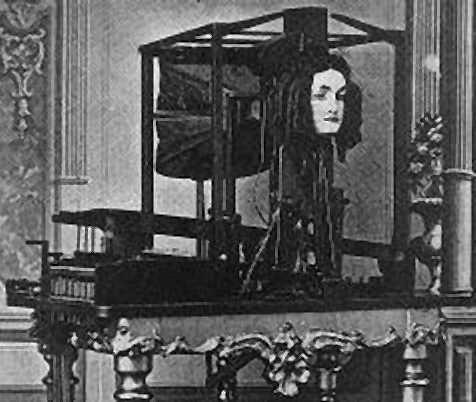

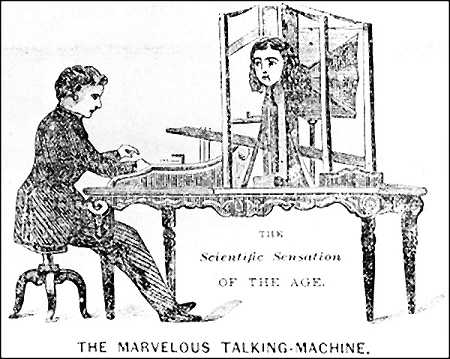

In December 1845, Joseph Faber exhibited his "Wonderful Talking Machine" at the Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia. This machine, as recently described by writer David Lindsay, consisted of a bizarre-looking talking head that spoke in a "weird, ghostly monotone" as Faber manipulated it with foot pedals and a keyboard.

Just prior to this public exhibition, Joseph Henry, [left], visited Faber’s workshop to witness a private demonstration. Henry’s friend and fellow scientist, Robert M. Patterson, had tried to drum up financial support for Faber, a beleaguered German immigrant struggling to earn a living and learn how to speak English. Henry, who was often asked to distinguish fraudulent from genuine inventions, agreed to go with Patterson to look at the machine. If an act of ventriloquism was at work, he was sure to detect it.

Just prior to this public exhibition, Joseph Henry, [left], visited Faber’s workshop to witness a private demonstration. Henry’s friend and fellow scientist, Robert M. Patterson, had tried to drum up financial support for Faber, a beleaguered German immigrant struggling to earn a living and learn how to speak English. Henry, who was often asked to distinguish fraudulent from genuine inventions, agreed to go with Patterson to look at the machine. If an act of ventriloquism was at work, he was sure to detect it.Instead of a hoax, which he had suspected, Henry found a "wonderful invention" with a variety of potential applications. "I have seen the speaking figure of Mr. Wheatstone of London," Henry wrote in a letter to a former student, "but it cannot be compared with this which instead of uttering a few words is capable of speaking whole sentences composed of any words what ever."

Henry observed that sixteen levers or keys "like those of a piano" projected sixteen elementary sounds by which "every word in all European languages can be distinctly produced." A seventeenth key opened and closed the equivalent of the glottis, an aperture between the vocal cords. "The plan of the machine is the same as that of the human organs of speech, the several parts being worked by strings and levers instead of tendons and muscles."

Henry, who in 1831 had invented a demonstration telegraph while pursuing his electromagnetic investigations, believed that many applications of Faber’s machine "could be immagined [sic]" in connection with the telegraph. "The keys could be worked by means of electro-magnetic magnets and with a little contrivance not difficult to execute words might be spoken at one end of the telegraphic line which have their origin at the other." A devout Presbyterian, Henry immediately seized upon the possibility of having a sermon delivered over the wires to several churches simultaneously.

Joseph Faber’s "Euphonia", as shown in London in 1846.

The machine produced not only ordinary and whispered speech, but it also sang the anthem

"God Save the Queen".

"In December 1845, Joseph Faber exhibited his "Wonderful Talking Machine" at the Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia. This machine, as recently described by writer David Lindsay, consisted of a bizarre-looking talking head that spoke in a "weird, ghostly monotone" as Faber manipulated it with foot pedals and a keyboard.

"... a speech synthesizer variously known as the Euphonia and the Amazing Talking Machine. By pumping air with the bellows ... and manipulating a series of plates, chambers, and other apparatus (including an artificial tongue ... ), the operator could make it speak any European language. A German immigrant named Joseph Faber spent seventeen years perfecting the Euphonia, only to find when he was finished that few people cared."

The earliest speaking machines were perceived as the heretical works of magicians and thus as attempts to defy god. In the thirteenth century the philosopher Albertus Magnus is said to have created a head that could talk, only to see if destroyed by St. Thomas Aquinas, a former student of his, as an abomination. The English scientist-monk Roger Bacon seems to have produced one as well. That fakes were appearing in Europe in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries is shown by Miguel de Cervantes’s description of a head that spoke to Don Quixote -- with the help of a tube that led to the floor below. Like Magnus, this fictitious inventor also feared the judgement of religious authorities, though in his case he took it upon himslef to destroy the heresy. By the eighteenth century science had started to shed its connection to magic, and the problem of artificial speech was taken up by inventors of a more mechanical bent."

David Lindsay, "Talking Head", Invention & Technology, Summer 1997, 57-63.

...Faber, who had destroyed an earlier version of his talking machine out of frustration over an unappreciative public, apparently felt encouraged by the response of Henry and Patterson to his new machine. In 1846, he accompanied P. T. Barnum to London, where the "Euphonia," as it was now called, was put on display at London’s Egyptian Hall. The exhibit drew an endorsement from the Duke of Wellington and remained a part of Barnum’s repertoire for the next several decades. The financial returns for Faber, however, were meager. He would die in the 1860s without achieving the fame or fortune he sought.

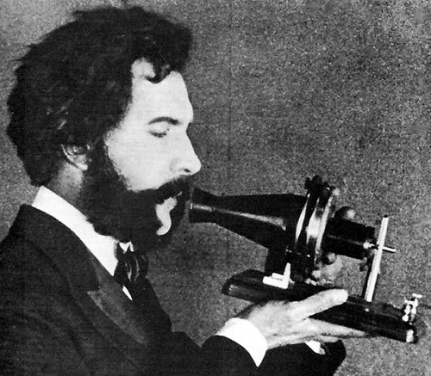

Faber would thus not live to witness the most important outcome of his invention. By a curious twist of fate, one person who happened to see the Euphonia in London in 1846 and come away deeply impressed was Melville Bell, the father of Alexander Graham Bell...

--- Joseph Henry and the Telephone

It was Bell’s own efforts to simulate speech, initially through constructing mechanisms similar to Faber’s, that eventually led him to try the modulation electric current. Joseph Henry, himself a pioneer of the field of electromagnetism and by that time (1874) the first director of the Smithsonian Institute, immediately grasped the importance of Bell’s invention. He became Alexander Graham Bell’s first and most influential supporter.

Once again Mark over at Language Log provides links to additional information about Faber’s contraption and its predecessors and successors, most notably the one created by the brilliant inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen (which formed the basis of Wheatstone’s mentiond above).

Article from: laputanlogic.com

Alexander Graham Bell with an early model of the telephone, an invention that owes much to Faber’s advances.

"Faber’s story is almost archetypical. He artfully played the role, whether aware of it or not, of the disheveled monomaniac who produced work that was shockingly advanced for its time, but which was not valued during his life. His inglorious death, followed many years later by posthumous respect, further cements this identity. An immigrant, an isolated genius, a professional failure, and a victim of suicide, Faber was a casualty on the battlefield of technological progress, only given his due respect decades after his bones were as cold and dead as the spectral face of the Euphonia itself."

Source