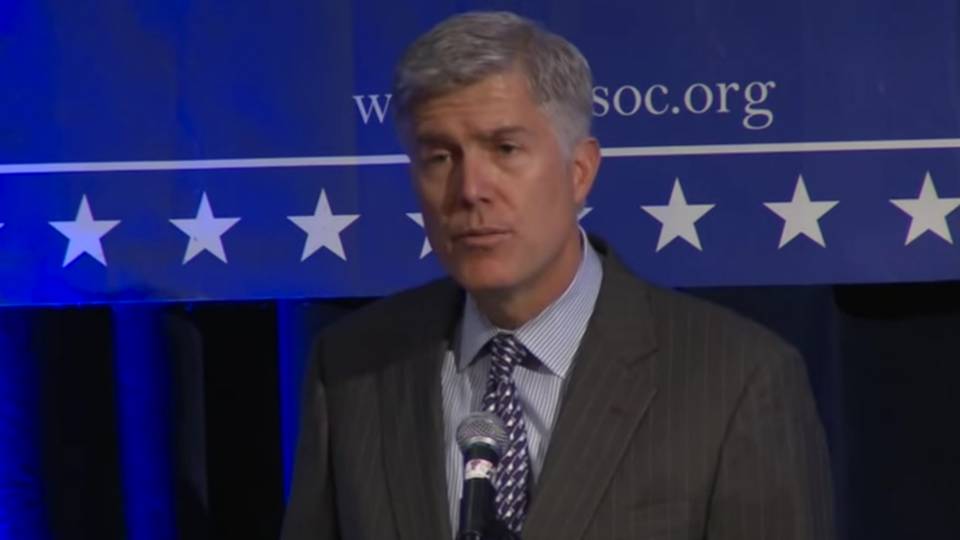

Neil Gorsuch, Donald Trump's Supreme Court Nominee, Explained

Donald Trump has selected Neil Gorsuch, a 49-year-old federal appeals court judge on the 10th Circuit, as his choice to fill the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat on the Supreme Court.

Gorsuch is a widely acclaimed jurist, a favorite of conservatives and libertarians but also very respected by liberal colleagues. He’s exactly the kind of elite, educated figure who's traditionally made it onto the Court. His mother, Anne Gorsuch Burford, was Ronald Reagan's director of the Environmental Protection Agency from 1981 to 1983. A graduate of Columbia (where he was a Truman scholar), Oxford (where he got a doctorate under the acclaimed Catholic legal philosopher John Finnis as a Marshall scholar), and Harvard Law (which five other members of the Court attended), Gorsuch clerked on the DC Circuit and then for both Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy before working at a boutique litigation firm in Washington, DC, for 10 years and doing a brief stint in the George W. Bush Justice Department.

So it’s perhaps not surprising that when Bush appointed to him to the 10th Circuit — which covers much of the Mountain West, including Gorsuch's home state of Colorado — at the age of 38, he was easily confirmed by voice vote.

This time should be different. Gorsuch is more outspoken and forthright in his positions than your typical Supreme Court aspirant, providing a lot of fodder for any opponents. A Democratic filibuster motivated by Republicans’ successful obstruction of President Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, for this same seat last year is a certainty for any nominee, and if Democrats conclude that Gorsuch’s views on issues like the right to life and religious liberty are outside the mainstream, the filibuster might have a chance of success.

Gorsuch is a solid conservative, but an eloquent and thoughtful one

Most of the time, the dominant portion of what we know about potential Supreme Court picks comes from their records as appellate judges. What’s less common is for a nominee to have written lengthy works of scholarship on contentious issues likely to come before the Court.

But so it is with Gorsuch, who wrote a full book on assisted suicide and euthanasia that, while fairly recapping both sides, came down decisively against legalizing the practice. In the book, Gorsuch offers a detailed critique of Peter Singer’s influential utilitarian argument for allowing euthanasia and of a similar one from fellow Circuit Court Judge Richard Posner, as well as critiques of autonomy-based arguments from philosophers like Ronald Dworkin.

Gorsuch argues for the position that "human life is fundamentally and inherently valuable, and that the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong." He insists this is a secular principle that one need not be religious to embrace. It's not hard to infer what this implies for Gorsuch's attitudes on abortion, despite his never stating clearly his views on Roe v. Wade and the like in the book.

While not directly ruling on abortion or right-to-life issues as a judge, Gorsuch’s jurisprudence has touched on a few other hot-button areas, as SCOTUSblog’s Eric Citron notes in a good rundown of his notable rulings. Overall, Citron depicts Gorsuch as a jurist very much in line with Scalia, including on some areas where Scalia departed from other conservatives. A former law clerk describes Gorsuch as having a "deep commitment to the original understanding of the constitution and the rule of law." Gorsuch delivered a speech after Scalia's death (an event which he stated moved him to tears) praising his possible predecessor for understanding the distinction between judge and legislator, and for striving not to use the Court to make law.

Gorsuch takes a very broad view of religious freedom, and in two separate cases (one of which was the famous Hobby Lobby case) backed religious challenges to the Affordable Care Act. “No one before us disputes that the mandate compels Hobby Lobby and Mardel to underwrite payments for drugs or devices that can have the effect of destroying a fertilized human egg,” he wrote in a concurrence. “No one disputes that the Greens’ religion teaches them that the use of such drugs or devices is gravely wrong.” Under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, Gorsuch argued, the government must give broad deference to religious groups’ explanations of what their beliefs entail, even if those explanations seem inconsistent or unscientific.

Given how controversial Hobby Lobby remains among reproductive rights activists, expect Democratic senators to raise that issue repeatedly during Gorsuch’s confirmation hearings. In fairness to Gorsuch, he also ruled in favor of a Native American prisoner in another religious liberty case, indicating his views on this aren’t limited to Christians.

In a trio of cases, Gorsuch has argued for the constitutionality of religious expression in public spaces, including in cases where only one religious tradition is represented (as in the display of a donated Ten Commandments monument). He has argued against the “reasonable observer” test for determining if religious displays are unconstitutional, writing that the test too often results in the rejection of religious displays that were not intended to signal that the government is endorsing one religion or another. This, again, should resonate with religious conservatives concerned about courts restricting Christian religious displays by local governments.

Like Scalia, he has shown a willingness to occasionally side with defendants on criminal law matters. He sided with a Albuquerque middle schooler who was strip-searched by his school, dissenting while his colleagues ruled that the school police officer and other employees are immune from lawsuits. In one 2012 dissent, he argued against applying the federal law banning felons from owning firearms to a defendant who had no idea he was a felon. And he's expressed concern with overcriminalization, saying that states and the federal government have enacted too many statutes forbidding too much activity. But on other matters, he has been, like his would-be predecessor, harsher. He has taken a limited view of a defendant's right to competent representation, and tends not to view death penalty challenges favorably.

Citron notes that Gorsuch, like Scalia, has shown support for federalism by arguing against the idea of a "dormant commerce clause," or the idea that the Constitution's Commerce Clause not only allows Congress to regulate interstate commerce but bans states from doing so. For example, he wrote an opinion upholding a Colorado state clean energy program against a challenge alleging it would hurt coal producers from out of state.

The biggest difference between Gorsuch and Scalia is on matters of administrative law. Gorsuch has suggested that he thinks Chevron v. NRDC, a foundational decision that gives regulatory agencies broad deference in determining rules, was wrongly decided. That could give plaintiffs — whether they’re businesses wanting laxer rules or advocacy groups wanting tougher ones — more say in the rulemaking process.

But more than his individual decisions, what sets Gorsuch apart from other Supreme Court hopefuls is the high intellectual esteem in which he’s held by fellow judges and legal academics. That raises hopes among conservatives that whatever his jurisprudential overlap with Scalia, he would bring the same literary flair and intellectual firepower to the Court that Scalia’s admirers believe he did. And for liberals, that will likely provoke fears that he could wield similar influence to Scalia on the right bloc of the Court, and on conservatives in lower courts.

His overall philosophy is similar to Scalia’s, but he’s personally close to Kennedy

The overlaps between Gorsuch and Scalia become clear when you read the speech Gorsuch delivered after Scalia’s passing. Beyond its personal encomia devoted to Scalia, the speech lays out Gorsuch’s fundamental approach to interpreting law and the Constitution, which is very similar to the late justice’s. Both are textualists, concerned primarily in the literal text of laws and less in their legislative history or social context of passage.

Gorsuch also speaks admiringly of the approach taken by Supreme Court Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan’s opinion and dissent, respectively, in last year's case of Lockhart v. US, a criminal appeal concerning whether a mandatory minimum sentence applied to a defendant convicted of a sex offense. The justices disagreed sharply, but their disagreement was solely over how to interpret a vague antecedent in the text of the statute establishing the mandatory minimum.

“Neither [the opinion nor the dissent] appealed to its views of optimal social policy or what the statute ‘should be,’” Gorsuch said. “Their dispute focused instead on grammar, language, and statutory structure and on what a reasonable reader in the past would have taken the statute to mean — on what ‘the words on the paper say.’”

Of course, many cases before the Supreme Court do not reduce to such issues. Many legal scholars would argue that interpreting the law often involves invoking controversial moral or political principles or “filling in the gaps” in places where the textual and common law is unclear or incomplete, and skeptics of strict textualism in particular argue that this approach is incapable of dealing with such “hard cases.” This dispute becomes especially heated around constitutional interpretation, given that provisions like the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses arguably invoke moral concepts whose meaning changes and evolves along with society.

Gorsuch presents a forceful argument that cases of indeterminacy are, in practice, quite rare. Supreme Court cases that don’t result in a unanimous decision account for only 0.014 percent of all federal court cases. This suggests, he argues, that 99.986 percent of cases do have a determinate, uncontroversial answer. This isn't an airtight argument — some of this is due to the Supreme Court's only being able to handle a finite workload, and also due to some parties to cases not having the resources to appeal — but it’s a good reminder that a large portion of the work of appellate and Supreme Court judges is on matters that don’t arouse public controversy.

He continues, “Even accepting some hard cases remain — maybe something like that 0.014 percent — it just doesn’t follow that we must or should resort to our own political convictions, consequentialist calculi, or any other extra-legal rule of decision to resolve them.” When simple textual interpretation of the laws and evidence at hand does not point in the direction of one obvious result, that process will still come closer to accuracy, he argues, than importing the moral or political values of the judge handling the case.

By contrast, he argues that judging cases based on the social benefits of each possible outcome creates even more problems with indeterminacy. "In hard cases don’t both sides usually have a pretty persuasive story about how deciding in their favor would advance the social good?” he asks. “In criminal cases, for example, we often hear arguments from the government that its view would promote public security or finality. Meanwhile, the defense often tells us that its view would promote personal liberty or procedural fairness. How is a judge supposed to weigh or rank these radically different social goods?”

This echoes an influential argument by the legal philosopher Joseph Raz for the proposition that some values are simply incommensurable, and can’t be weighed against each other — which, if true, Gorsuch argues has major implications for the law. Of course, the counterargument here is that in claiming to not consider the social consequences of a ruling, textualists like Gorsuch tend in practice to arrive at decisions that produce conservative outcomes, suggesting the approach isn’t as neutral and non-ideological as its proponents present it as being.

Gorsuch’s speech doesn’t stake out clear positions on hot-button topics. But it is worth a read to get a sense of his overall philosophical standpoint on the role of judges.

Beyond his overall jurisprudence, however, he would be the first justice ever to serve alongside a justice for whom he clerked, namely Anthony Kennedy (John Roberts, a former William Rehnquist clerk, came close, but Rehnquist died shortly after Roberts’s initial nomination and Roberts was re-nominated to replace him). That gives conservatives some hope that Gorsuch will be able to sway Kennedy on crucial cases, solidifying the conservative bloc and ensuring a 5-4 conservative majority on key issues.