Putting electronics in a spin

Source: news.bbc.co.uk

Spintronics harnesses the spin of sub-atomic particles |

But this speedy number cruncher could soon look like the equivalent of a dusty abacus if scientists who have gathered in York deliver on their promises.

Nearly 150 of them have convened in the medieval town to explore the future of spintronics (spin-based electronics), an area that could have profound effects on areas as diverse as data storage, microelectronics and quantum computing.

"With quantum computing you are able to attack some problems on the time scales of seconds, which might take an almost infinite amount of time with classical computers," said Professor David Awschalom of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Endless possibility

Spintronics, also known as magnetoelectronics, is an emerging technology that harnesses the spin of particles.

Conventional electronics ignores these rotations and instead exploits the movement or accumulation of electrons to do useful calculations or store data.

Spintronics is already used in MRAM devices produced by Freescale |

But, by harnessing the twist and turns of particles - detected as a weak magnetic force - scientists hope to unlock almost infinite computing power and storage, without the heat.

"If you think about the spin of a particle, such as an electron, it can point up or down or at any superposition of the two; partially up or partially down," said Professor Awschalom.

Each of these different "superpositions" can represent an almost infinite number of combinations of ones and zeros.

"You can store an almost infinite number of bits of information in one particle space," he added.

This almost limitless number of possibilities would also pave the way for advanced computer processing, such as is needed in quantum computing.

"The spin of a particle is a very natural particle for quantum information processing," said Professor Awschalom.

Next generation

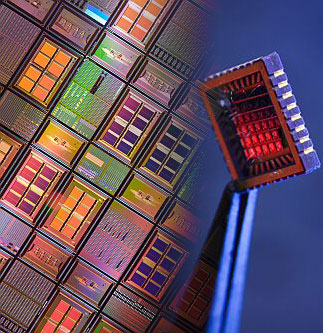

This type of advanced computation is still a long-way off, but hi-tech companies intent on packing ever-increasing power and storage into smaller and smaller areas, are already taking spintronics seriously.

"The conventional microelectronics industry and the magnetic storage industry are approaching their limits very fast. Spintronics might offer a way out," said Dr Yongbing Xu of the University of York.

Inside the hard drive |

For example, most hard drives today use a "spin valve", a device that reads information off the individual disks or platters that make up a hard drive.

"That enabled a thousand fold improvement in the storage capacity of disk drives from when we introduced it in 1998," said Dr Stuart Parkin of computer giant IBM and the inventor of the device.

He describes the spin valve as part of "the first generation" of spintronic devices, relatively simple structures built of magnetic materials.

Second generation devices, he said, have also recently hit the shelves in the form of a type of computer memory known as MRAM (Magnetoresistive Random Access Memory). In 2006, chip firm Freescale began to offer 1MB MRAM devices for example.

These devices are a hybrid of a hard disk and more up to date types of memory, such as flash memory, commonly used in digital cameras.

Like flash, MRAM has no moving parts and retains all of its data even when the power is switched off. But, like a hard drive, it stores data as magnetic charges.

But, Dr Parkin is already working on what he believes could be the third generation of spintronic memory devices.

Back and forth

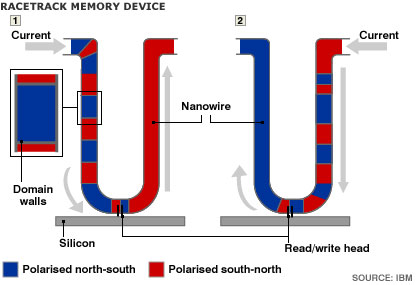

He is currently building a spintronic prototype of what he calls "racetrack memory", a device that could increase storage density by up to 100 times.

It achieves this by building "high-rise" chips.

"The racetrack is a very tall column of magnetic material; it is essentially a magnetic nanowire standing on end above the surface a silicon wafer," said Dr Parkin.

Along the nanowire would be polarised regions, magnetised to point towards the north or south pole.

"The boundary between these regions is a magnetic domain wall and that is where the information is stored."

Spintronics could render today's supercomputers obsolete. More: Blue Gene/L

The domain walls are moved up and down the U-shaped wire by applying a tiny pulse of spin-polarised current - a flow of electrons all spinning in one direction - to either end of the wire.

When the electrons make contact with a domain wall it moves it along the wire, shuffling the data like train carriages being shunted around a track.

"You're not moving any atoms you're just moving a magnetic orientation," he said.

The data would be read by a simple read/write device at the bottom of the "U".

A working device would look like a small forest of nanowires covering the surface of a chip. But, it could be some time before racetrack memory is common place.

"It will probably take another five years before we have a complete prototype."

First steps

But this maybe long before researchers are able to build one of the holy grails of spintronics, a semiconductor that integrates both computer processing and storage.

"In that case it would be faster and it would consume less energy [than today's semiconductors]," explained Dr Xu.

A key challenge of building advanced devices is controlling and manipulating the spin of atoms so that the data, in the form of different spin orientations, can be written and read accurately.

"In the last few years people have been able to read one single spin and manipulate it," said Professor Awschalom. "Now some of the challenges are to do a lot of these operations efficiently."

Material researchers also need to come up with new materials that allow these operations to be done at room temperature, rather than the impractical sub-zero temperatures used in the lab.

And when that happens, spintronics may truly have come of age.

"We could make a computer that is completely different than what we are using today," said Dr Xu.

WUN-SPIN 2007 runs from 7-10 August at St William's College, University of York.