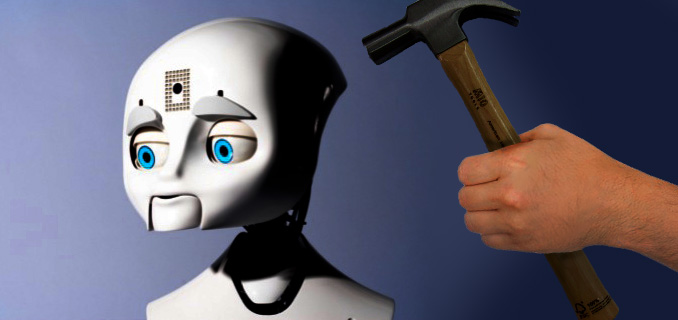

Robot Rights: Is it OK to torture or murder a robot?

Scientists are talking rights for robots when human rights are still something we frequently struggle for. Are rights for intimate objects necessary or prudent? Could you eventually face punishment for trashing your toaster?

In her talk, MIT researcher Kate Darling illustrates how difficult it is for people to torture or kill inanimate objects, such as cute robots. These findings are hardly surprising, as we know that humans readily anthropomorphize objects, especially if the object possesses the qualities of a living being - familiar physical features, communicative feedback like expression or reaction.

Could the findings suggest nothing about robots, but everything about humans - that most people, by their very nature, simply aren’t inherently prone to violence? (A nice thought.)

With the knowledge that humans empathize with robots, might robots be used to effectively guide and control our behavior?

Technology is creating the possibility for humans to become more and more robot-like with implantable robotics, high tech prosthetics, and advanced medical technologies. A future where humans are bionic may blur the lines between man and machine. Will we require new rights for those that become ’new humans’?

More on robot rights and how we relate to machines from BBC...

---

Is it OK to torture or murder a robot?

By Richard Fisher | BBC

We form such strong emotional bonds with machines that people can’t be cruel to them even though they know they are not alive. So should robots have rights?

Kate Darling likes to ask you to do terrible things to cute robots. At a workshop she organised this year, Darling asked people to play with a Pleo robot, a child’s toy dinosaur. The soft green Pleo has trusting eyes and affectionate movements. When you take one out of the box, it acts like a helpless newborn puppy – it can’t walk and you have to teach it about the world.

Yet after an hour allowing people to tickle and cuddle these loveable dinosaurs, Darling turned executioner. She gave the participants knives, hatchets and other weapons, and ordered them to torture and dismember their toys. What happened next “was much more dramatic than we ever anticipated,” she says.

For Darling, a researcher at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, our reaction to robot cruelty is important because a new wave of machines is forcing us to reconsider our relationship with them. When Darling described her Pleo experiment in a talk in Boston this month, she made the case that mistreating certain kinds of robots could soon become unacceptable in the eyes of society. She even believes that we may need a set of “robot rights”. If so, in what circumstance would it be OK to torture or murder a robot? And what would it take to make you think twice before being cruel to a machine?

Until recently, the idea of robot rights had been left to the realms of science fiction. Perhaps that’s because the real machines surrounding us have been relatively unsophisticated. Nobody feels bad about chucking away a toaster or a remote-control toy car. Yet the arrival of social robots changes that. They display autonomous behaviour, show intent and embody familiar forms like pets or humanoids, says Darling. In other words, they act as if they are alive. It triggers our emotions, and often we can’t help it.

For example, in a small experiment conducted for the radio show Radiolab in 2011, Freedom Baird of MIT asked children to hold upside down a Barbie doll, a hamster and a Furby robot for as long as they felt comfortable. While the children held the doll upside down until their arms got tired, they soon stopped torturing the wriggling hamster, and after a little while, the Furby too. They were old enough to know the Furby was a toy, but couldn’t stand the way it was programmed to cry and say “Me scared”.

It’s not just kids that form surprising bonds with these bundles of wires and circuits. Some people give names to their Roomba vacuum cleaners, says Darling. And soldiers honour their robots with “medals” or hold funerals for them. She cites one particularly striking example of a military robot that was designed to defuse landmines by stepping on them. In a test, the explosions ripped off most of the robot’s legs, and yet the crippled machine continued to limp along. Watching the robot struggle, the colonel in charge called off the test because it was “inhumane”, according to the Washington Post.

Killer instinct

Some researchers are converging on the idea that if a robot looks like it is alive, with its own mind, the tiniest of simulated cues forces us to feel empathy with machines, even though we know they are artificial.

Earlier this year, researchers from the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany used an fMRI scanner and devices that measure skin conductance to track people’s reactions to a video of somebody torturing a Pleo dinosaur – choking it, putting it inside a plastic bag or striking it. The physiological and emotional responses they measured were much stronger than expected, despite being aware they were watching a robot.

Darling discovered the same when she asked people to torture the Pleo dinosaur at the Lift conference in Geneva in February. The workshop took a more uncomfortable turn than expected.

After an hour of play, the people refused to hurt their Pleo with the weapons they had been given. So then Darling started playing mind games, telling them they could save their own dinosaur by killing somebody else’s. Even then, they wouldn’t do it.

Finally, she told the group that unless one person stepped forward and killed just one Pleo, all the robots would be slaughtered. After much hand-wringing, one reluctant man stepped forward with his hatchet, and delivered a blow to a toy.

After this brutal act, the room fell silent for a few seconds, Darling recalls. The strength of people’s emotional reaction seemed to have surprised them.

Given the possibility of such strong emotional reactions, a few years ago roboticists in Europe argued that we need new set of ethical rules for building robots. The idea was to adapt author Isaac Asimov’s famous “laws of robotics” for the modern age. One of their five rules was that robots “should not be designed in a deceptive way... their machine nature must be transparent”. In other words, there needs to be a way to break the illusion of emotion and intent, and see a robot for what it is: wires, actuators and software.

Darling, however, believes that we could go further than a few ethical guidelines. We may need to protect “robot rights” in our legal systems, she says.

If this sounds sound absurd, Darling points out that there are precedents from animal cruelty laws. Why exactly do we have legal protection for animals? Is it simply because they can suffer? If that’s true, then Darling questions why we have strong laws to protect some animals, but not others. Many people are happy to eat animals kept in awful conditions on industrial farms or to crush an insect under their foot, yet would be aghast at mistreatment of their next-door neighbour’s cat, or seeing a whale harvested for meat.

The reason, says Darling, could be that we create laws when we recognize their suffering as similar to our own. Perhaps the main reason we created many of these laws is because we don’t like to see the act of cruelty. It’s less about the animal’s experience and more about our own emotional pain. So, even though robots are machines, Darling argues that there may be a point beyond which the performance of cruelty – rather than its consequences – is too uncomfortable to tolerate.

[...]

Read the full article at: bbc.com

Tune into Red Ice Radio:

Kevin Warwick - I, Cyborg, Implants, Cybernetics, AI & The Rise of the Machines in 2020

Aaron Franz - TransAlchemy, Save the Humans! & Transhuman Fundamentalism