Sisterhood of the Skulls

Source: forteantimes.com

The Neapolitan caves where a cult of old women "adopt" human skulls and commune with the dead

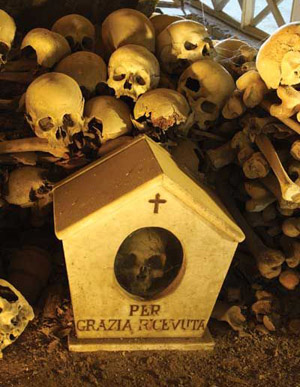

A row of skulls at Fontanelle, including several in shrines provided by women who had "adopted" them.

Naples has a reputation for being Italy’s city of greatest extremes. The gap between rich and poor is nowhere more visible; despite being devoutly pious, the city is also more crime-ridden and mob-controlled than any in the country; and in all respects Neapolitans seem to pursue life with a visible – even maniacal – passion.

The occult side of Naples is equally extreme, and the city is one Italy’s most mysterious and superstitious. One of its greatest enigmas was a strange cult, composed almost exclusively of elderly women who communed with the dead, lavishing their attention on, and even making offerings to, human skulls.

The cult was centred on a cemetery known as the Fontan elle.

The “cemetery” is in fact a huge (5,000 sq m / 54,000 sq ft) ossuary in a man-made cave and series of adjoining grott oes. Malle able tufa, deposited by local volcanoes, was easily manipulated by ancient Greek colonists, who began a system of tunnels that the Romans and then early Christians extended. The high walls within the main cavern of the Fontanelle marked the northern boundary of the old Greek city. This area – just outside the city – had always been used as a place to deposit bodies, and the Romans and Christians each constructed burial catacombs nearby.

An enshrined skull – "Per grazia recevuta" thanks the deceased for services rendered.

By 1500, a large quantity of bones had already accumulated in the cave, and over the next century and a half this mass was greatly augmented as the spacious site became the standard depository for victims of plague and other epidemics.

This store of bones and cadavers remained out of sight and out of mind until the end of the 17th century, when a series of floods washed great quantities of it down the hill and into the heart of the city. Seeing downtown Naples sudd enly inundated by a river of the anonym ous dead, the city fathers decided the cave would have to be organised into a more formal ossuary complex, giving birth to the Fontanelle Cemetery, as it is now known.

The deposits were further added to as the cave became increasingly recognised as an official cemetery – in partic ular the de facto paupers’ cemetery and final resting place for the city’s indigent poor.

The piles of bones were not the only things growing in the cave, however.

A curious cult dedicated to the remains began to evolve around the site, especially after 1872. In that year, Father Gaetano Barbati had large deposits of bones exhumed, and the skulls were cleaned and placed on racks or in troughs, where they took on the role of devotional items for this death-obsessed group.

There was no formal organisation to this cult, but it rapidly grew popular with older women, especially widows or those with little or no family. They claimed to receive messages from the deceased in their dreams, and would then “adopt” whichever skull they believed had belonged to the spirit that had contacted them, becoming in effect a kind of caretaker of not just the remains but also the soul of the dead person.

They would clean and care for their skulls, even constructing engraved marble shrines for them. These boxes might enclose a single skull, or multiples if the same person adopted more than one.

Cult devotees would bring flowers and gifts as offerings for their chosen crania, and address them by name. The dead at the Fontanelle were of course anonymous, but this army of old ladies claimed the skulls would reveal their true names to their benefactors.

In return for this doting care, the deceased would grant favours to their devotees, who would petition the skulls for assistance in a variety of forms – through dreams, direct conversation, various forms of telepathy, or by writing their requests on small slips of paper, which would be rolled up and inserted into the skulls’ eye sockets.

The shrines in which adherents housed their adopted charges were frequently inscribed with messages thanking the skulls for various favours or services; usually the inscriptions were simple, something along the lines of “Per Grazie Recev uta” (thanks for what was given). But they could be more elaborate, even containing names.

The inscribed names were not those of the deceased, however, but rather those of the skulls’ benefactors. The devotees were highly possessive of their skulls, and the shrines were not intended solely to show gratitude to the deceased, but also to mark a specimen as having been adopted, a sign to potential rivals that they should find their own skull and not commune with remains which were already spoken for.

Some of the boxes even included doors with locks and chains, as some people didn’t want anyone else to be able even to look upon their skulls.

Since the cult had no formal structure, records of the number of adherents were not kept, but by the end of the 19th cent ury the group had by all accounts reached a high point. Enough people frequented the site to warrant building a church in front of it, as well as a subterranean, dirt-floored chapel space at the entrance to the actual cemetery.

Other additions occurred especially under Father Gaetano, including a kind of Greek temple façade made from wood and bones, with Christ standing in a doorway in the centre as if He were emerging from His tomb, and a mock-up of Calvary at one end of the cave with empty crosses placed above mounds of skulls.

The members of the “necrophiliac” group based on the Fontanelle were not so interested in these more orthodox types of religious sentiment, however.

Their dev–otions were primarily inspired by a different and surprising mechanism: lottery numbers.

One might beseech the dead for any number of favours, but the typical requests made of the skulls at the Fontanelle, on which all this devotion was lavished, centred on an obsessive desire for precognition of winning lottery numbers.

The city’s lottery was held on Saturday, and Friday saw the largest crowds descend into the cave as devoted old ladies tended to their skulls, bringing offerings and beseeching communion in the hopes of receiving the winning combination for a big score. The skulls of monks in particular were believed to have exceptional powers to predict the lottery; given the anonymity imposed by the bone pile, of course, it was impossible to ascertain who had in fact been a monk, but the skulls could reveal this information to their devotees in dreams, and in any event a skull which consistently provided correct numbers would be assumed to have been a member of a religious order.

Such a motivation – lottery numbers – seems mundane for a cult of the dead, and on a deeper level there was indeed more to it than that.

Mario Alamaro, who is involved in caring for the site on behalf of the city, points out the unique psychology that would come with the cult’s key demographic of older women who had little or no family. He believes that adopting and caring for a skull provided the devotee an attachment and outlet for affection that they might not have otherwise had. “I consider it to have been a coping mechan ism,” he says, “a kind of substitute for the people they might have lost.” And indeed, the cult’s second great flourish came in the period immediately after World War II, when many Neapolitan women had in fact lost their husbands or other family members.

While lottery numbers were considered among the skulls’ greatest gifts, the requests made of the deceased were not always so mercenary. The aid of the bones would also be beseeched when family and friends were ill, or to help with various dom estic problems. One skull, considered to be “public property,” was understood to aid infertile women.

Young women who could not bear children were encouraged to come to the cemetery and caress it – with the consequence that it became the most smoothly polished skull in the ossuary, as generat ions of women rubbing it over in the hopes of getting pregnant left it, even today, with an almost supernatural sheen.

Another skull is enshrined in a box inscribed with the owner’s thanks, and the date “6 September, 1943”. In fact, that was the date of the heaviest allied bombing of Naples in the war.

During air raids, the Fontanelle became a makeshift bomb shelter, especially for devotees of the site who found strength and hope in the presence of their adopted skulls. As the bombs fell on 6 September, someone apparently begged a particular skull for protection, and attributed her own survival to its powers, rewarding it with a shrine.

Not surprisingly, the skulls at the Fontanelle figure prominently in the city’s occult lore.

The most famous story involves a skull known as “The Captain” – he is the centre skull at the base of the middle of the three Calvary crosses. “The Captain” was considered the most active entity in the cave and there were numerous stories about him, but the most famous involved a young couple. Unlikely as it may seem, the Fontanelle also served as a kind of “Lover’s Lane”, as amorous couples with nowhere else to go would sometimes come to the cave late at night for their liaisons.

In the late 19th century, a devout young girl was convinced by her less than pious boyfriend to accompany him to the Fontanelle and give up her virginity. Immediately afterward, meditating on her act, the girl spoke to “The Captain”; she asked the skull for a blessing so that the relationship would turn into a happy marriage. Overhearing this, her boyfriend mocked her super stition. He stuck a rod into “The Captain’s” eye socket and dared him, if any of the stories be true, to show up at the wedding. Eventually the couple did marry. At the banquet, they noticed an unknown man enter wearing an anachronistic officer’s uniform. When the stranger got up to leave, the groom followed him out, cornered him, and demanded to know who had invited him. The officer turned and smiled, answering: “You did, at the Fontanelle,” and “The Captain” opened his coat to reveal a full skeleton.

As far as the Roman Catholic Church was concerned, the cult based on the Fontanelle was wholly unacceptable. If this was all just superstition, it had degenerated into a form of heathen fetishism, and if any of the stories about mysterious occult happenings were true then it was something even worse. The Church became convinced that the place would have to be shut down; the only surprise is that, perhaps fearing a local backlash, it took them until 1969 to actually do it, when Card inal Corrado Ursi ordered the premises perm anently closed. The Fontanelle languished after its closure, and by now most of the devotees of the site have passed on and become what they once adored. For brief periods, it has been open for tourism, but even that is no longer permitted, and it now receives few visitors – mostly just scholars and VIPs.

“But we do get some Satanists who break in and hold Black Masses down here, and we have to chase them out,” Alamaro acknowledges.

By the year 2000, the Fontanelle had degenerated into a dirty and chaotic bone heap. Not wanting to lose this unique piece of local history entirely, the city of Naples began a series of efforts at restoration and reconstruction. Alamaro describes an incident that occurred when the work began, which recalls not only the heyday of the cult, but the unanswered question of whether there was, in fact, something more at work at the Fontanelle than just super stition.

When renovation work first began, an old woman showed up at the gates and demanded to be let in. The crew refused, but she proved persistent and eventually they relented. She told them she needed to speak with Pasquale, and asked where he could be found. The workers informed her that there was no one working there named Pasquale. But he was not part of the crew, she explained – Pasquale was the skull that had once been hers. The site had been closed for 31 years, and the crew explained that it would be impossible to locate a single skull; there were many thousands of them, and the original arrangements had all been disturbed, with things falling over and moved, and bones being pushed into giant piles. The lady determ ined to find Pasquale herself, and the puzzled workers watched her walk through the cave, calling for him. Event ually, she claimed, she heard him respond, and digging through a pile she emerged with a skull that she said had once been her Pasquale. She sat down and had a long conversation with him.

The restoration crew mostly just found the incid ent amusing – until later, when they were cleaning out the deposits under the area where she had retrieved the skull and found fragments of a broken wooden plaque with the letters “–quale” on it. It seemed as if the old lady had in fact been right. Pasquale’s skull and the remains of his nameplate are today kept in a glass case inside a shrine provided by his benefactor. Standing near the entrance of the cemetery, he serves as a reminder that even though nowadays most people consider the story of the cult of death that was once based here to be simply a local curiosity, the connection between the living and dead at the Fontanelle, at least in this case, may have been something much deeper.

The shrine containing "Pasquale". To the right of the glass case is the broken name plate with a name ending in "-squale", which was buried near where the skull was found.

Author: Paul Koudounaris lives in Los Angeles, where he teaches Baroque Art History. He has spent the last year preparing material for a book about surviving charnel houses and bone-decorated chapels in Europe and South America. He hopes to publish this material within the next year.

Article from: ForteanTimes.com