The Dark Roots of the EU

Source: brusselsjournal.com

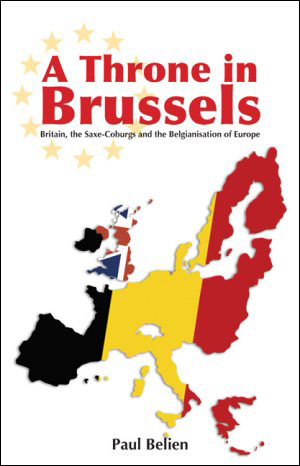

Belgium was founded exactly 175 years ago, in 1830. The cover of A Throne in Brussels, the book I wrote for its anniversary, depicts the map of the European Union in the Belgian colours. This is no coincidence. As Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt recently said: “Belgium is the laboratory of European unification. Foreign politicians watch our country with particular interest because it can teach them something about the feasibility of the European project.”

Belgium was founded exactly 175 years ago, in 1830. The cover of A Throne in Brussels, the book I wrote for its anniversary, depicts the map of the European Union in the Belgian colours. This is no coincidence. As Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt recently said: “Belgium is the laboratory of European unification. Foreign politicians watch our country with particular interest because it can teach them something about the feasibility of the European project.”Two peoples live within the Belgian state: Dutch-speaking Flemings and French-speaking Walloons. In 1830 the country was part of the Dutch-speaking Netherlands. The Belgian revolution was the work of French-speaking rebels who wanted to have it annexed to France. The international powers stepped in and, by way of compromise, decided to make Belgium an independent kingdom with at its helm a German prince, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, who was a member of the British royal family.

Leopold I of Belgium |

In 1865, the year of his death, Leopold I, the prince who had been given the crown of Belgium, told his son that “nothing holds the country together” and that “it cannot continue to exist.” To his secretary, Jules Van Praet, he said “Belgium has no nationality and […] it can never have one. Basically, Belgium has no political reason to exist.”

Belgium’s history is the dramatic search of its leaders for unifying elements which would be able to compensate for the lack of nationhood and the absence of genuine and generous patriotic feelings in their country. By the late 19th century the Belgian political elite developed the ideology of “Belgicism.” This “Belgicism” bears a striking similarity to contemporary “Europeanism.” Just listen to what the Belgicist ideologue Léon Hennebicq, a Brussels lawyer, wrote in 1904:

“Have we not been called the laboratory of Europe? Indeed, we are a nation under construction. The problem of economic expansion is duplicated perfectly here by the problem of constructing a nationality. Two different languages, different classes without cohesion, a parochial mentality, an adherence to local communities that borders on the most harmful egotism, these are all elements of disunion. Luckily they can be reconciled. The solution is economic expansion, which can make us stronger by uniting us.”His words foreshadow the Europeanist project of the 1950s which aimed for political unification through economic integration. Apart from a Belgicist, however, Hennebicq was also a socialist. He did not attach importance to economic growth for its own sake – the creation of wealth which would benefit the people – but because Belgium needed economic expansion in order to be able to literally buy the adherence of the Flemings and the Walloons to their artificial state. The Belgicists were aware that Belgium could only become a viable country, if it was turned into a huge redistribution mechanism, a welfare state.

After the first World War the Belgicists imposed a social-corporatist system on Belgium. Since 1919, economic and social policies are no longer decided in parliament, but in consensus between the so-called “Social Partners.” These Social Partners include the Federation of Belgian Employers, which is the official representative of the employers versus the state. In addition it includes three specific trade unions (a Christian-Democrat, a Socialist and a Liberal one), which are recognised by the state as the only official representatives of the employees. The social partners are by nature Belgicist institutions: they operate in both Flanders and Wallonia and have huge financial and political interests in both parts of the country.

Henri Pirenne |

Paul-Henri Spaak |

De Man knew that Belgium, as an artificial construct, did not really exist as a nation. The Belgian state was no more than the corporatist welfare system run by the “social partners.” All that being a Belgian nationalist meant was that one was attached to the Belgian welfare state. In a february 1937 interview De Man said: “What Spaak and I mean by national socialism is a socialism that attempts to achieve all that can be achieved within the national framework.” He went on to state that the Belgian welfare system could – and should – eventually be replaced by a pan-European or even a global welfare system. “I insist on being a good European, a good world citizen, as much as on being a good Belgian,” de Man said. He reckoned that if one had to live in an artificial welfare state, it would be better to live in one on as large a scale as possible. The Belgian model had to be applied at a European level.

Henri De Man |

De Man’s deputy, Paul-Henri Spaak, who had fled to France in May 1940, tried to return to Belgium during the Summer, but was not allowed in by the Germans. Hence, against his wishes he ended up in Britain. At the time he deplored this. Later it would turn out to have been his good fortune. Otherwise, like De Man, he would have ended up as a Nazi collaborator. Instead, Spaak survived the war on the winning side.

Though Henri De Man is now forgotten by history, his political legacy is very much alive. Spaak remained loyal to De Man’s vision of Belgium as a multi-national social-corporatist welfare state that was to be elevated to the European level. Spaak became one of the Founding Fathers of the European Union. Though he was an arch-opportunist, with few loyalties, he did not betray De Man’s dream of one single European welfare state. According to Spaak’s 1969 memoirs, De Man was “one of those rare men who on some occasions have given me the sensation of a genius.”

In 1956, Spaak authored the so-called Spaak Report which laid the foundation of the Treaty of Rome the following year. It recommended the creation of a European Common Market as a step towards political unification. From the beginning the views of the people about all this was deemed unimportant. In his memoirs, Spaak admits that “political opinion was indifferent. The work was done by a minority who knew what they wanted.”

Given the roots of Europeanism in Belgicism, there is a lot to be learned from Belgium’s characteristics as an artificial non-national state. Verhofstadt is right when he says that foreign politicians watch his country with particular interest because it can teach them something about the feasibility of the European project. The European superstate shares more than just its capital with Belgium. If the so-called Europeanists have their way, it is also going to be a Greater-Belgium.

In my book I describe three characteristics of Belgium that have already infected Europe. Firstly, as there is no genuine patriotism, the state has had to buy the adherence of the people by literally corrupting them. The absence of the virtue of generous patriotism forces the political leaders to make hard-headed calculated self-interest the foundation of the state. It is not a coincidence that Belgium is plagued by corruption to a degree that is higher than in neighbouring countries. It is not a coincidence that corruption is plaguing the European institutions also.

A second characteristic of Belgium throughout its history has been the absence of the rule of law. If the existence of the state is at stake, laws and even the constitution will be ignored in order to secure the continued existence of Belgium. As the state is an artificial construct that is unloved by the people, this happens quite regularly. Many examples are to be found in Belgium’s 175 years of existence. In fact there never was a majority in the Belgian parliament to introduce the social-corporatist model of the Belgicists in 1919. About this episode the historian Luc Schepens wrote: “It is not inappropriate to state that the worst war casualties in Belgium were the Constitution and the parliamentary democracy – albeit out of necessity and in the name of the continuity of the State.” Today, out of necessity and in the name of the continuity of the European project, Europeanists want to ignore the rejection of the European Constitutional Treaty by the peoples of Europe.

The third characteristic of an artificially constructed state is its unreliability in international relations. A state that is not committed to the rule of law, is not committed to its friends and allies either.

Article from: The Dark Roots of the EU

More on the roots and Monarchy of Belgium of and King Leopold II: White King, Red Rubber, Black Death (Video)