The First Eden - Part One

Source: thevesselofgod.com

The Face of the Deep

It is remarkable how many creation myths have nearly identical beginnings. They begin with tales of a primordial chaos, and that chaos is usually symbolized by the element of water. For the Babylonians, the goddess Tiamat (“the bitter ocean”) represented the chaos which spawned all things. She took as her husband Apsu, the god of the fresh waters. This union of bitter ocean and fresh waters is certainly suggestive of a flood, and this idea is borne out by the fact that their son Ea equates with the Sumerian King Ia, who was known to history as “the Lord of the Flood.”

The Egyptian story of creation also begins with water and chaos. Before the gods there was only a dark, watery abyss called Nun. Within its chaos, Nun contained the potentiality of all things and the latent divinity of the creator. At the dawn of the world a primeval mound arose from the waters, providing the first deity with a place to come into being. Finding himself alone, he created the world and peopled it with gods and men patterned on his image. This first deity became the Sun God who brought light and order to where darkness and chaos once reigned.

These are but a few examples out of many. Most are not incredibly dissimilar to what is found in Genesis, where it says: “And the earth was without form and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face o the waters.” (Emphasis ours.) Like the Egyptian deity, Jehovah also created order out of chaos, brought light into the darkness, and created man in his own image. Virtually identical stories are told by cultures existing in parts of the world far distant from these. The striking similarities between so many creation myths cannot be explained as mere coincidence. They have to represent a shared primordial memory of some sort. We think they do. We think the symbolism of chaos and a vast watery abyss is related to another of man’s most widespread myths - that of the Flood.

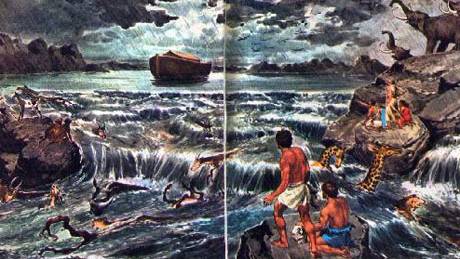

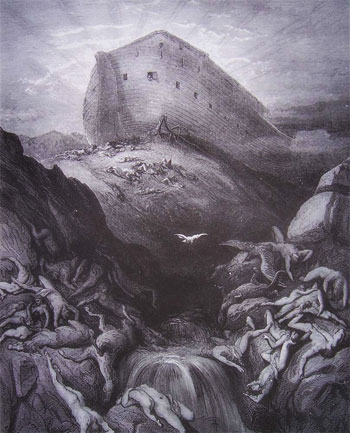

Nearly every culture recounts the tale of a global flood. Nearly every culture has a Flood hero who survives the Deluge, along with a remnant of humanity, to repopulate the Earth. We believe that the Flood represents the true starting point of our current historical epoch, and that it represents the end of the previous epoch - one referred to by many cultures as “the First Time.” Plato records that the Egyptian priests told Solon the Earth was far older than the Greeks thought, and that it had been ravaged by fire and floods repeatedly. Each time there was enough of a remnant left living to start anew. Could this be the reason why, in the first chapter of Genesis, God says to Adam, “...be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth”? The commandment is fairly unambiguous. Though contrary to the storyline, God is clearly telling Adam to be fruitful, multiply, and repopulate the earth.

The story of Eden is a highly symbolic account, containing elements of both truth and fiction. Those aspects that reflect the most historical accuracy are the various names involved, which can be shown to relate to very real figures in the Sumerian king lists. “King Ia” is Adam, his son “Kin” is Cain, the third king “Enu” is Enoch, and so on. But the king lists may also contain clues which shed light on the fictional aspects of the Eden story. The Sumerians also had an antediluvian king list, which is generally regarded as a work of fiction. It purports to document a glorious pre-history of Sumer - one that stretched back 241,000 years into the past. Some of the kings included on the list were said to have lived exceedingly long lives, a few to the age of 30,000. Sumeriologist L.A. Waddell was able to demonstrate that this antediluvian king list could be patterned upon names and alternate titles of figures in the post-Flood king lists, and that the fabrication had probably been an attempt on the part of the Sumerians to reconstruct that part of their history which had been lost or forgotten. Authors of the Old Testament, using the Sumerian prototype as a guide, started their tale with the post-Flood figures, later inserting the story of the Flood out of sequence. We find support for our thesis, yet again, in the strange figure of Enoch.

Central to the lore of Enoch is the notion that he preserved the lost wisdom of the antediluvian world. The question such an idea naturally raises is this: How could a figure who vanishes from biblical texts before the Flood (not to reappear thereafter) be expected to have accomplished such a task? Even in The Book of Enoch, he dispatches his “antediluvian” wisdom well before any suggestion of a coming deluge. Enoch’s story only makes sense if Noah’s story didn’t happen in the way it is presented. And evidence exists to suggest that this is precisely the case.

As unorthodox as such as idea may seem, there is evidence indicating that Enoch and Noah were really the same figure. In some ancient texts the name “Noah” is rendered as “Noach”, while elsewhere Enoch is presented as “Noach.” Joseph Riess, author of Language, Myth and Man, believes that Noah, Noach and Enoch are all alternate names for the same figure. L.A. Waddell, citing different evidence, also believes Noah and Enoch to be one and the same. According to Waddell, Enoch was sometimes called “Hanuk”, and in certain translations of Genesis Noah is called “Hanuk” as well. Also, a tradition exists among the Chaldeans specifically linking the third Sumerian king Enu (Enoch) to the legend of the Flood. Enu’s son bore the royal title of Ia-patesi (“Priest-King of God Ia”), which Waddell believes is preserved in the name of Noah’s son, Iapeth, or Japeth. Waddell even states that, “Enoch... is regarded by Biblical authorities as being identical with Noah of the Flood myth.”1 If such an idea was in currency with the Biblical scholars of Waddell’s time (the 1920s), it doesn’t seem to have taken hold. And yet it is immanently logical. If Enoch piloted the Ark, it would explain how it was he who was credited with preserving the secrets of the antediluvian world. In The Book of the Cave of Treasures, it is said that one of the most sacred things taken aboard the Ark was a text containing “the most ancient secrets of the church” - the very secrets synonymous with the legend of Enoch.

Presuming that Enoch piloted the Ark necessitates a complete rethinking of the chronology contained in Genesis, and would require viewing the events described as history told in highly symbolic terms. It is altogether possible that this may in fact have been the intent of the original authors, and that they have left enough clues for us to read between the lines. Comparing the details of Genesis with the traditions from which it was derived provides further clues still.

Presuming that Enoch piloted the Ark necessitates a complete rethinking of the chronology contained in Genesis, and would require viewing the events described as history told in highly symbolic terms. It is altogether possible that this may in fact have been the intent of the original authors, and that they have left enough clues for us to read between the lines. Comparing the details of Genesis with the traditions from which it was derived provides further clues still.Let us start with a simple hypothesis: Could the story of Adam’s expulsion from Eden be emblematic of a previous Golden Age empire coming to an end? And could the ensuing banishment to a wasteland symbolize the condition of a planet left devastated by a flood? Virtually every culture had a legend of a “Golden Age” sometimes in the mythical past. Perhaps the most well-known of these is that of Atlantis. Like the stories of Genesis, Atlantis is intimately connected with ideas of a fall from grace, divine retribution, and a flood. The history of Sumer begins with a flood; the story of Atlantis ends with one. Many mainstream scientists and experts now concur that such a flood did in fact occur. Is it a tale rooted in history, and not myth? Could it be possible that Atlantis was the first Eden?

Let us take a closer look at the most pertinent details of both stories. Both take place in a primordial paradise of perfection, a place whose “soil produced a wealth of roots, wood, gums, flowers and fruits, the sweet juice of the grape, and corn, all desirous... vegetables... shady trees sheltered it’s happy people, and diverse fruits appeased their hunger and thirst... in a word, there was to be found ... everything which could satisfy the body, the spirit, and engender piety towards the gods.” The foregoing description, so evocative of the Biblical Eden, is in fact Plato’s description of Atlantis. It wholly reflects the popular conception of Eden, though in The Book of Genesis Eden is never described with such a vivid wealth of detail.

In both stories, the end of the idyllic paradise is precipitated by a rebellion against the gods (or “God”, as the case may be). Divine punishment ensues, and the Golden Age comes to an end. Perhaps the oddest theme to be shared by both stories is that of giants. In both stories, giants are the result of miscegenation between gods and mortals - or more precisely, between gods and mortal women. Could such startling similarities be pure coincidence, or do the stories of Eden and Atlantis have a shared origin? Are the Watchers of The Book of Enoch synonymous with the antediluvian gods, perhaps the survivors of the island’s destruction?

The White Gods

The stories of the Watchers, of Dagon and Oannes are, as we know, not unique. Nearly identical tales are told in virtually every corner of the globe. The only explanation that seems to make sense of such stories is surprisingly simple and straight-forward: they represent the interaction of peoples from radically different cultures. Imagine for a moment that people fleeing the destruction of a high civilization turned up in a society incredibly less advanced than their own? What might the local inhabitants make of them? How might the natives perceive a group of strangers possessing technology wholly unknown to them, possibly a people who looked, dressed and spoke differently than themselves - a people of perhaps far greater stature than any with whom they’d ever come into contact? Very possibly, they might be looked upon as gods.

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America, the indigenous population though they were witnessing the return of the white gods who had visited their people in antiquity, promising one day to return. There were in for an unpleasant shock. In our own time, we have the phenomenon of the “cargo cult.” During WWII, pilots used a sparsely populated island in the Pacific to set down their cargo planes. To ensure the peaceful cooperation of the native populace, they gave them food and gifts. The locals assumed these people were gods, and when the visitors had left, ritualistic runways were constructed in their honor, and wooden fetishes shaped like planes became objects of worship. The example of the cargo cult is probably not altogether different from the sort of interactions that spawned the mythologies of so many tutelary deities: the wise teachers (or ancestor gods) who appeared to so many peoples “at the dawn of time” to bequeath their wisdom. We can choose to believe one of two things about these figures: either that they were really gods who enjoyed sharing the secrets of geometry, astronomy, agriculture and architecture; or that there was in fact a race of men at that time who had this knowledge. We can at least assume that that tales told of them constitute some form of truth, because any people fabricating their own history would surely concoct something far more self-aggrandizing.

If these cultures had developed geometry, astronomy, etc. on their own, they would surely take pride in that fact, and take credit for it in their own history. If they hadn’t developed it themselves, yet produced artifacts that clearly demonstrate a knowledge of it, then it stands to reason that they must have learned it from someone else. Not only are the stories of tutelary deities nearly identical, often even the names of the figures are incredibly similar.

In short, it seems highly unlikely that such stories are mere myths or fabrications. Orthodox historians would dismiss these tales, because they fall outside the parameters of our conventional view of history. At the same time, historians seem to be at a loss to satisfactorily explain away the stunning similarities found in such myths as the following, from virtually every corner of the globe:

Some of the names of these gods reveal specifically Atlantean connotations, while a full two-thirds of them contain root words relating to water or the sea. The name “Tule”, for instance, is all but identical to the Northern European designation for Atlantis, “Thule.”2 In some ancient cultures the word for the sea was phonetically pronounced “tl”, which serves as the root for “Atl.” And “Atl”, in turn, can be found in both “Atlas” and “Atlantis.” Over half of the names on this list contain the root words “Mer”, “Mar”, or “Mur”, all of which relate to the sea in numerous languages both ancient and modern. A connection also seems evident between these figures and the story of the tutelary god already discussed, Muru, or Maru3 (Dagon). He is identified as the second Sumerian deified king, Kan, the biblical Cain. His “Maru” title is of special interest, because it ties into our thesis relating the legend of Atlantis to the place remembered as Eden.

According to L.A. Waddell, the Sanskrit word “Maru” has the same meaning as the Sumerian word “Etin”, or “Eden.” Plato has made evident in his Criteas and Timeaus that the name of Atlantis (and those of its gods) had been rendered into Greek, so as to be more comprehensible to readers of his native land. But other traditions relating the story of Atlantis give it the name of “Merou.” So if Atlantis is synonymous with Merou, and Maru is synonymous with Eden, might it be possible that Atlantis (Merou) and Eden (Maru) actually refer to the same place? We believe so. We have already presented evidence supportive of the fact that the figures of Enoch and Noah can both be traced to the third Sumerian king Enu, and that in the Chaldean flood legend it was he who piloted the Ark. Further support for this is found in the Sumerian king lists compiled by the Erech dynasty, in which his title is given as “Shepherd of the Vessel.” Might not such a title easily be interpreted to mean “pilot of the Ark?”

If Eden was Atlantis, and Enoch piloted the Ark that preserved the remnant of its populace, it is very probable that two of the passengers on that vessel would have been his father and grandfather; that is to say: the first two kings of Sumer - the biblical Adam and Cain. As we explore the myths of the tutelary deities from the new world, the foregoing thesis will begin to seem less and less like some wild fantasy, and increasingly like a credible possibility. We will demonstrate what appear to be tangible links between the figures in these tales, and those central to both Genesis and early Sumer. Though these myths are virtually identical to those already discussed, there is a fundamental difference: the indigenous peoples assert that these gods arrived following the destruction by flood of their sacred homeland - an island.

Foam of the Sea

In the highest peaks of the Andean mountains lie the ruins of Cuzco, a cyclopean city built of massive stones weighing many tons each. In the region, it is said that a “white god” who was “very tall” had built this city in ancient times. He had come from across the sea, and thus was given the name “Viracocha”, meaning “foam of the sea.” These peaks are widely separated from the sea, and so seem to support the idea that in ancient times a flood had occurred which had made them more accessible. Other ancient cities on the continent remained undiscovered until the 1980s, because they rested on peaks so high that they were shrouded in clouds. There is a good possibility that other such cities exist in South America, atop great mountains surrounded in fog.

In the highest peaks of the Andean mountains lie the ruins of Cuzco, a cyclopean city built of massive stones weighing many tons each. In the region, it is said that a “white god” who was “very tall” had built this city in ancient times. He had come from across the sea, and thus was given the name “Viracocha”, meaning “foam of the sea.” These peaks are widely separated from the sea, and so seem to support the idea that in ancient times a flood had occurred which had made them more accessible. Other ancient cities on the continent remained undiscovered until the 1980s, because they rested on peaks so high that they were shrouded in clouds. There is a good possibility that other such cities exist in South America, atop great mountains surrounded in fog.In The Royal Commentaries of the Incas by Garcilaso de la Vega, it is clear that the beginning of their history coincides with the Flood: “After the waters of the Deluge had subsided, a certain man appeared in the country of Tiahuanaco... .” That man was known as Viracocha, Manco Capac, Illa, and to the Aztecs, as Quetzalcoatl. The author continues:

“In the life on Manco Capac, who was the first Inca, and from whom they began to boast themselves children of the Sun... they had an ample account of the Deluge. They say that in it perished all races of men and created things insomuch as the waters rose above the highest mountain peaks in the world. No living thing survived except a man and a woman who remained in a box and, when the waters subsided, the wind carried them... to Tiahuanaco, where the creator began to raise up the people and nations that are in the region... .”

This, of course, tends to reinforce our theory that the Flood represented the true genesis of our current epoch. But there are even more intriguing correspondences. The name of Manco Capac’s descendants, the “Inca”, has more than a passing resemblance to Cain’s Mesopotamian title, “Enki“. The story being told is very much the same, and so too are many of the names involved. Viracocha is the Andean name for this figure. In the Yucatan he was called “Noach Yum Chac.” He was also known as “Illa”, which equates with the Chaldean “Ila”, and the Mesopotamian “Ellu” - “The Shining One.” Even the name “Andes” seems to allude to the Mesopotamian god-name of “An.”

It was said that Viracocha could call down “fire from the heavens.” If he caused this fire to consume a huge rock, that rock would become “light as a cork”, and could be easily be used for such constructions as can still be seen at Cuzco. In Andean legends, it is asserted that this Cyclopean city was built in a single night.

Like Dagon and Oannes, Viracocha taught the people to read and write, how to plant crops and till the field, and various magical arts. But there is an even more tangible link between the figure of Viracocha and the Sumerian fish gods. A statue of Viracocha exists which depicts him as a white man with a long beard. From the waist up he is normal in appearance, but from the waist down he is covered in fish scales.

“... The people of our nation were much terrified at seeing a strange creature much resembling a man riding on the waves. He had upon his head long green hair, [and] a beard of the same color... from his breast down he was actually a fish, or rather two fishes, for each of his legs was a whole and distinct fish. And he would sit for hours singing to the wondering ears of the Indians of the beautiful things he saw in the depths of the ocean, always closing his strange stories with these words: ‘Follow me, and see what I will show you.’ For a great many suns, they dared not venture upon the water; but when they grew hungry, they at last put to sea, and following the fish-man, who kept close to the boat, reached the American coast.”

A related tale is told by the same author of Mexico’s “Huchucton-acateao-cateao-upatle, or Fish-god-of-our-flesh... [who] somewhat resembled the Noah of sacred writ; for... in a time of great flood, when the Earth was covered with water, he rescued himself in a cypress trunk, and peopled the world with wise and intelligent beings.” This figure may or may not be the same as Quetzalcoatl, the “white god” who came to the Aztecs and erected a series of massive ziggurats. Though often depicted symbolically as a feathered white serpent, Quetzalcoatl was said to have been a bearded white man who “was very tall.”

Could it be possible that all of these stories are describing various people’s encounters with the same person? Perhaps a more appropriate question would be, “What is the likelihood that they are not? The details of the stories, though mythic and seemingly improbable, all seem to correspond to one another. What are the chances that people so geographically remote from one another (the Middle East, North America, and South America) would all contrive the same tale, unless it really happened to them?

What elevates such tales from the realm of mere comparative mythology is the fact that that they are connected to physical evidence which attests to their truth. The cities said to have been built by these “mythical” figures still exist, and defy all explanation. On the shore of Lake Titicaca there is a dock carved of solid stone which weighs 440 tons. In Mexico there is a ziggurat dedicated to Quetzalcoatl that has a base of forty-five square acres - larger than the pyramid of Khufu. In Sacsayhuanan, North of Cuzco, there are gigantic walls made of stones weighing between 100 and 361 tons. Whoever created such works had powers and abilities which modern man, with all of his technology, is at a loss to replicate. It is easy to see why the so-called “primitive” peoples of these regions may have viewed the creators of these monuments as gods.

Stay Tuned for Part Two

Article from: http://www.thevesselofgod.com/thefirsteden.html