The I Ching is an uncertainty machine

Source: aeonmagazine.com

Forget prophecy and wisdom. Using the I Ching is a weirdly useful way to open your mind to life’s unexpected twists

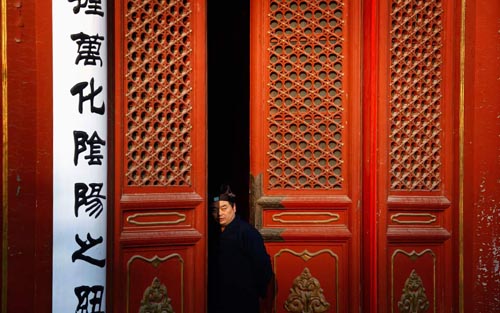

I stepped into the dark of the ramshackle hillside temple. It was a hot day, and the climb had been steep. There were no other tourists around. The only people I passed on my way up the mountainside steps were two pious old ladies, pausing to catch their breath as they struggled through the afternoon heat.

Inside it was cool, the air fragrant with incense. To one side of the door was a table, and behind the table sat a small, neat man in the robes of a Daoist priest. A handwritten sign in front of him announced that temple entrance was two yuan (20p). I paid my fee and he smiled. ‘Welcome,’ he said. I peered into the dark, where deities and mythological beasts clamoured for attention on the painted walls.

I had visited other temples elsewhere in China, in larger cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou and Wuhan; but there I had blended in among the hopeful devotees and noisy tourists. Here, on the other hand, I was on my own, and felt somehow out of place, unsure how to conduct myself. The priest, however, was in a chatty mood. ‘Where do you come from?’ he asked me in Chinese.

‘England,’ I told him.

He smiled. One of his front teeth was missing. ‘What are you doing in China?’

I told him I was writing a book.

‘A book about China?’ he asked.

I hesitated. I had heard the old joke several times now. When foreigners come to China for a month or two, they go home and write a book. When they have been there for several months more, they write an article. If they have lived in China for more than a year, they end up writing nothing. I was in China for only a couple of months. I hesitated about what to say, then I decided I might as well tell him. ‘It is about the I Ching,’ I said. ‘I am writing a book about the I Ching.’

I was in China in pursuit of an obsession that, among certain of my more sober-minded and rational friends, was the cause of some alarm. For the previous few years, I had been increasingly preoccupied by that strangest of books, the Chinese Book of Changes or I Ching. In the West, the I Ching is mainly known as a divination manual, found on shelves alongside books about tarot cards, crystal healing, reiki, and contacting your angels, a part of the wild carnival of spurious notions that is New Age spirituality, that great tide of unreason against which the prophets of scientific rationality protest in vain. I knew the arguments against the I Ching: divination doesn’t work, it belongs to the realm of prescientific superstition, it is a primitive attempt to tame the uncertainty of the future. I had heard these arguments many times, and they made sense to me; and yet there was something about the I Ching that continued to fascinate me, something that — the more I studied it — could not allow me to dismiss this book so lightly.

My interest in the I Ching had begun several years before, neither as a fascination with Chinese culture, nor as a mystical concern with divinatory practices, but instead in the course of a rambling and idle conversation with a friend. It was 2006, and I was casting around for a fresh writing project. My first novel was due out in the following year. I wanted something new and substantial to work on, but I had no clear sense of direction. At some point during our conversation, we found ourselves talking about the taste for astrology, tarot cards and other forms of prognostication. I was happily pouring scorn on these practices, protesting at their unreason, when my friend interrupted me. ‘Perhaps,’ he said, ‘it is not about predicting the future.’

‘What is it about, then?’ I asked.

My friend shrugged. ‘Perhaps it is about imagining new possibilities.’

I was momentarily silenced. ‘Perhaps,’ I said. Then the conversation moved on, but the thought stuck with me. I was in need of new possibilities. And, after all, hadn’t Italo Calvino, a writer I loved, played with tarot cards in his book The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973)? So, a few days later, I went to the bookshop, made my way to the Mind, Body and Spirit section, and tentatively picked up a copy of the I Ching: Or Book of Changes, first published in 1951 in a handsome red-and-black jacket, and now in a Penguin edition, with Richard Wilhelm’s German text translated by Cary F Baynes and the rather flaky foreword by Carl Jung.

I had come across the I Ching numerous times before on the bookshelves of friends, and had even tried to read it on occasion, but always given up, frustrated by the thickets of obscurity it presented. As I stood in the bookshop flicking through the I Ching, my knowledge of the book was fairly rudimentary. I knew that it was a divinatory text, divided into 64 chapters, with each of these chapters headed by a six-lined symbol, referred to in English as a ‘hexagram’ and in Chinese as guaxiang. I knew that each of the hexagrams was associated with a number of prognostications, and that the book was often put to use by tossing coins or sorting yarrow stalks, to randomly derive a hexagram made up of broken and unbroken lines.

[...]

Read the full article at: aeonmagazine.com