The Neverending Hunt for Utopia

Source: blogs.smithsonianmag.com

What is it that makes us human? The question is as old as man, and has had many answers. For quite a while, we were told that our uniqueness lay in using tools; today, some seek to define humanity in terms of an innate spirituality, or a creativity that cannot (yet) be aped by a computer. For the historian, however, another possible response suggests itself. That’s because our history can be defined, surprisingly helpfully, as the study of a struggle against fear and want—and where these conditions exist, it seems to me, there is always that most human of responses to them: hope.

The ancient Greeks knew it; that’s what the legend of Pandora’s box is all about. And Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians speaks of the enduring power of faith, hope and charity, a trio whose appearance in the skies over Malta during the darkest days of World War II is worthy of telling of some other day. But it is also possible to trace a history of hope. It emerges time and again as a response to the intolerable burdens of existence, beginning when (in Thomas Hobbes’s famous words) life in the “state of nature” before government was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short,” and running like a thread on through the ancient and medieval periods until the present day.

I want to look at one unusually enduring manifestation of this hope: the idea that somewhere far beyond the toil and pain of mere survival there lies an earthly paradise, which, if reached, will grant the traveler an easy life. This utopia is not to be confused with the political or economic Shangri-las that have also been believed to exist somewhere “out there” in a world that was not yet fully explored (the kingdom of Prester John, for instance–a Christian realm waiting to intervene in the war between crusaders and Muslims in the Middle East–or the golden city of El Dorado, concealing its treasure deep amidst South American jungle). It is a place that’s altogether earthier—the paradise of peasants, for whom heaven was simply not having to do physical labor all day, every day.

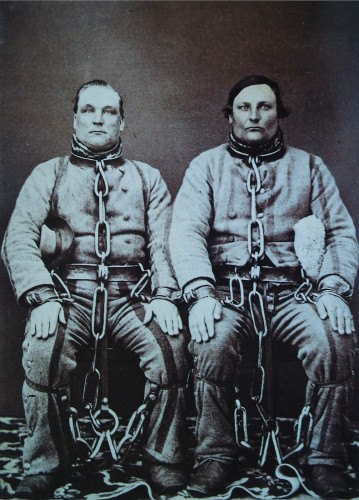

A photograph supposed to show a pair of Australian convicts photographed in Victoria c.1860; this identification of the two men is inaccurate–see comments below. Between 1788 and 1868, Britain shipped a total of 165,000 such men to the penal colonies it established on the continents’ east and the west coasts. During the colonies’ first quarter-century, several hundred of these men escaped, believing that a walk of as little as 150 miles would take them to freedom in China.

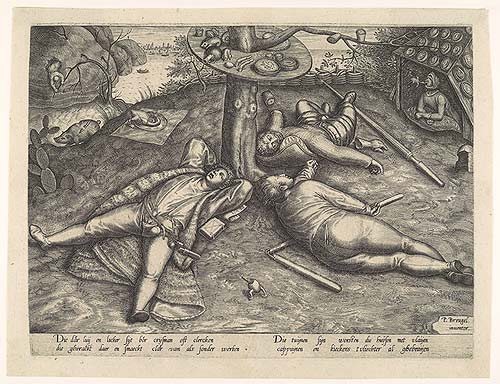

The Land of Cockaigne, in an engraving after a 1567 painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Cockaigne was a peasant’s vision of paradise that tells us much about life in the medieval and early modern periods. A sure supply of rich food and plenty of rest were the chief aspirations of those who sang the praises of this idyllic land. |

It is far from clear, from the fragmentary surviving sources, just how real the Land of Cockaigne was to the people who told tales of it. Pleij suggests that “by the Middle Ages no one any longer believed in such a place,” hypothesizing that it was nonetheless “vitally important to be able to fantasize about a place where everyday worries did not exist.” Certainly, tales of Cockaigne became increasingly surreal. It was, in some tellings, filled with living roasted pigs that walked around with knives in their backs to make it all the easier to devour them, and ready-cooked fish that leaped out of the water to land at one’s feet. But Pleij admits it is not possible to trace the legend back to its conception, and his account leaves open the possibility that belief in a physically real paradise did flourish in some earlier period, before the age of exploration.

Finnish peasants from the Arctic Circle, illustrated here after a photograph of 1871, told tales of the Chuds; in some legends they were dwellers underground, in others invaders who hunted down and killed native Finns even when they concealed themselves in pits. It is far from clear how these 17th-century troglodytic legends morphed into tales of the paradisiacal underground “Land of Chud” reported by Orlando Figes. |

[...]

Read the full article at: smithsonianmag.com

Cockaigne or Cockayne is a medieval mythical land of plenty, an imaginary place of extreme luxury and ease where physical comforts and pleasures are always immediately at hand and where the harshness of medieval peasant life does not exist. Specifically, in poems like The Land of Cockaigne, Cockaigne is a land of contraries, where all the restrictions of society are defied (abbots beaten by their monks), sexual liberty is open (nuns flipped over to show their bottoms), and food is plentiful (skies that rain cheeses). Writing about Cockaigne was a commonplace of Goliard verse. It represented both wish fulfillment and resentment at the strictures of asceticism and dearth.Wikipedia

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s "Luilekkerland" ("The Land of Cockaigne"), 1567. (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymus Bosch. Oil-on-wood panels, 220 x 389 cm, Museo del Prado

Tune into Red Ice Radio:

Jacque Fresco & Roxanne Meadows - The Venus Project, The Philosophy, The System & The Transition

Alex Newman - Hour 1 - Sweden’s Big Government ’Utopia’ Unmasked

Mike Cross - Hour 1 - Philosophy of a Psychopathic Society

Kevin Annett - The Crimes Against Humanity by Church and State

Christer Johansson - Hour 1 & 2 - Abduction of Domenic Johansson by Swedish Social Services

Alan Watt - Future Studies & Collectivism