The Tasmanian Tiger: Is the strange creature extinct or hiding from humans?

Tasmanian TigerFrom: Department of Environment. au

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is one of the most fabled animals in the world. Yet, despite its fame, it is one of the least understood of Tasmania’s native animals. European settlers were puzzled by it, feared it and killed it when they could. After only a century of white settlement the animal had been pushed to the brink of extinction.

Source

The thylacine looked like a large, long dog, with stripes, a heavy stiff tail and a big head. Its scientific name, Thylacinus cynocephalus, means pouched dog with a wolf’s head. Fully grown, it measured about 180 cm (6 ft) from nose to tail tip, stood about 58 cm (2 ft) high at the shoulder and weighed up to 30 kg. The short, soft fur was brown except for 13 - 20 dark brown-black stripes that extended from the base of the tail to almost the shoulders. The stiff tail became thicker towards the base and appeared to merge with the body.

Thylacines were usually mute, but when anxious or excited made a series of husky, coughing barks. When hunting, they gave a distinctive terrier-like, double yap, repeated every few seconds. Unfortunately there are no recordings.

The thylacine was shy and secretive and always avoided contact with humans. Despite its common name, ’tiger’ it had a quiet, nervous temperament compared to its little cousin, the Tasmanian devil. Captured animals generally gave up without a struggle, and many died suddenly, apparently from shock. When hunting, the thylacine relied on a good sense of smell, and stamina. It was said to pursue its prey relentlessly, until the prey was exhausted. The thylacine was rarely seen to move fast, but when it did, it appeared awkward. It trotted stiffly, and when pursued, broke into a kind of shambling canter.

Actual archival footage of the Tasmanian Tiger:

Video from: YouTube.com

Breeding

Breeding is believed to have occurred during winter and spring. A thylacine, like all marsupials, was tiny and hairless when born. It crawled into the mother’s rear-opening pouch, and attached itself to one of four teats. Four young could be carried at a time, but the usual litter size was probably three. As the pouch-young grew, the pouch expanded, and became so big that it reached almost to the ground. Large pouch-young had fur with stripes. When old enough to leave the pouch, the young stayed in a lair such as a deep rocky cave, well-hidden nest or hollow log, whilst the mother hunted.

Thylacine family at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, 1910.

Thylacines lived in zoos for up to 9 years, but never bred in captivity. Their life expectancy in the wild was probably 5-7 years.

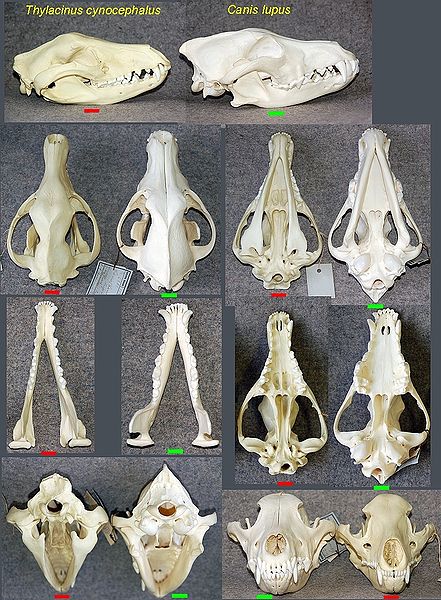

The skulls of the Thylacine (left) and the Timber Wolf, Canis lupus, are almost identical although the species are unrelated. Studies show the skull shape of the Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes, is even closer to that of the Thylacine.

Diet

The thylacine was a meat-eater - in fact, the world’s largest marsupial carnivore since the extinction of Thylacoleo,the marsupial ’lion’. Its diet is believed to have consisted largely of wallabies, but included various small animals and birds. Since European settlement, the thylacine also preyed upon sheep and poultry, although the extent of this was much exaggerated. Occasionally, the thylacine scavenged. In captivity, thylacines were fed on dead rabbits and wallabies, which they devoured entirely, as well as beef and mutton.

Distribution and Habitat

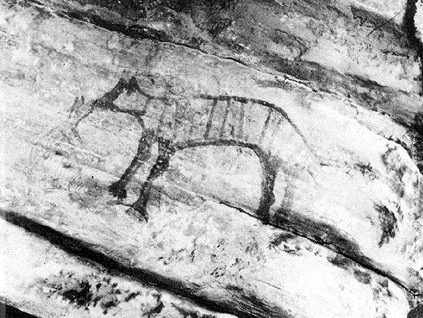

Possible Aboriginal cave painting of a thylacine and its cub in the Pilbara region of West Australia.

6000 years old.

Fossils and Aboriginal rock paintings show that the thylacine once lived throughout Australia and New Guinea. The most recent thylacine remains have been dated as being about 2,200 years old. Predation and competition from the dingo may have contributed to the thylacine’s disappearance from mainland Australia and New Guinea.

Bass Strait protected a relict population of thylacines in Tasmania. When Europeans arrived in 1803, thylacines were widespread in Tasmania. Their preferred habitat was a mosaic of dry eucalypt forest, wetlands and grasslands. They emerged to hunt on grassy plains and open woodlands during the evening, night and early morning.

Why are they extinct?

The arrival of European settlers marked the start of a tragic period of conflict that led to the thylacine’s extinction. The introduction of sheep in 1824 led to conflict between the settlers and thylacines.

1830 Van Diemens Land Co. introduced a thylacine bounties.

1888 Tasmanian Parliament placed a price of £1 on thylacine’s head.

1909 Government bounty scheme terminated. 2184 bounties paid.

1910 Thylacines rare -- sought by zoos around the world.

1926 London Zoo bought its last thylacine for £150.

1933 Last thylacine captured, Florentine Valley, sold Hobart Zoo.

1936 World’s last captive thylacine died in Hobart Zoo, ( 07/09/1936).

1936 Tasmanian tiger added to the list of protected Wildlife.

1986 Thylacine declared extinct by international standards.

Do they still exist?

In 1863, John Gould, a famous naturalist, predicted that the Tasmanian tiger was doomed to extinction:

In 1863, John Gould, a famous naturalist, predicted that the Tasmanian tiger was doomed to extinction:’When the comparatively small island of Tasmania becomes more densely populated, and its primitive forests are intersected with roads from the eastern to the western coast, the numbers of this singular animal will speedily diminish, extermination will have its full sway, and it will then, like the Wolf in England and Scotland, be recorded as an animal of the past...’

Every effort was made, by snaring, trapping, poisoning and shooting, to fulfil his prophecy. Bounty records indicate that a sudden decline in thylacine numbers occurred early in the 20th century. Hunting and habitat destruction leading to population fragmentation, are believed to have been the main causes of extinction. The remnant population was further weakened by a distemper-like disease.

The last known thylacine died in Hobart Zoo on 7th September, 1936.

Sightings and Searches

Since 1936, no conclusive evidence of a thylacine has been found. However, the incidence of reported thylacine sightings has continued. Most sightings occur at night, in the north of the State, in or near areas where suitable habitat is still available. Although the species is now considered to be ’probably extinct’, these sightings provide some hope that the thylacine may still exist.

There have been hundreds of sightings since 1936, many of which may have been clear cases of mis-identification. However, in a detailed study of sightings between 1934 and 1980, Steven Smith concluded that of a total of 320 sightings, just under half could be considered good sightings. Nonetheless, all sightings have remained inconclusive.

Interestingly, just as many sightings of equally good quality are reported from mainland Australia - perhaps a comment on the poor evidence that sightings alone represent.

There have been a number of searches for the animal. None of these searches have been successful in proving the continued existence of the animal. The results of a few of these searches are given below:

1937 - Sergeant Summers leads a search in the north-west of he state, recording many recent sightings by other persons in a large area between the Arthur and Pieman Rivers, although the party itself did not see any thylacines. He recommends a sanctuary in that area.

1945 - Well-known naturalist David Fleay searches the Jane River to Lake St Clair area, finding possible thylacine footprints.

1959 - Eric Guiler leads a search in the far north-west, an area which produced many bounties and finds what appeared to be thylacine footprints.

1963 - Eric Guiler leads a search in the Sandy Cape area but finds no evidence.

1968 - Jeremy Griffiths, James Malley and Bob Brown embark on a major search. Although they collect reports of sightings, they find no evidence of the thylacine.

1980 - Parks and Wildlife Officers, Steven Smith and Adrian Pyrke, search a wide area of the State using three automatic cameras. No evidence of thylacines is found.

1982-83 - Parks and Wildlife Officer, Nick Mooney, undertakes an extensive but unsuccessful search to confirm the 1982 sighting reported by Hans Naarding near the Arthur River in the State’s north-west.

1984 - A search in Tasmania’s highlands by Tasmanian Wildlife Park owner, Peter Wright, fails to turn up conclusive evidence.

1988-93 - Separate photographic searches by wildlife photographer, Dave Watts and Ned Terry fail to record a thylacine.

Hope for the Future?

The thylacine is the only mammal to have (possibly) become extinct in Tasmania since European settlement. This is in vivid contrast to mainland Australia, which has the worst record of mammalian extinctions of any country on Earth, with nearly 50% of its native mammals becoming extinct in the past 200 years. Tasmania is unique in that our fauna is abundant, and that the State acts as a refuge - a final hope - for many species that have recently become extinct on mainland Australia.

Despite our wishes to have a perfect record, the lack of any hard evidence of the thylacine’s continued existence supports the increasingly-held notion that the species is extinct. Nonetheless, the incidence of sightings introduces a reluctance among some authorities to make emphatic statements on the status of the species. Even if there did exist a few remaining individuals, it is unlikely that such a tiny population would be able to maintain a sufficient genetic diversity to allow for the viable perpetuation of the species in the long-term.

Recent attention has been given to the possibility of cloning the species. However, it is very unlikely to be achievable from a single individual preserved in alcohol. Even if cloning were possible, it should be asked whether such effort and expense is justifiable when many other species are currently threatened with extinction, and when we allow the same processes that threaten habitats and wildlife to continue.

Perhaps the lesson to be learned from the loss of the thylacine is to ensure that the rich natural heritage of our island State is no longer jeopardised.

Article from: DPIW.tas.gov.au

Debated Tasmanian Tiger Sighting 2009:

Murray McAllister has exclussive footage of a recent sighting of the Tasmanian Tiger (April 2009). This is 8 seconds from almost 9 minutes of footage.

Murray has been searching for evidence of the Tasmanian Tiger, long thought extinct, for several years. His web site http://www.tassietiger.org has more information.

Video from: YouTube.com

Wikipedia notes:

Unconfirmed sightings

The Australian Rare Fauna Research Association reports having 3,800 sightings on file from mainland Australia since the 1936 extinction date,[67] while the Mystery Animal Research Centre of Australia recorded 138 up to 1998, and the Department of Conservation and Land Management recorded 65 in Western Australia over the same period.[33] Independent thylacine researchers Buck and Joan Emburg of Tasmania report 360 Tasmanian and 269 mainland post-extinction 20th century sightings, figures compiled from a number of sources.[68] On the mainland, sightings are most frequently reported in Southern Victoria.[69]

Some sightings have generated a large amount of publicity. In 1973, Gary and Liz Doyle shot ten seconds of 8mm film showing an unidentified animal running across a South Australian road. However, attempts to positively identify the creature as a thylacine have been impossible due to the poor quality of the film.[70]

In 1982 a researcher with the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service, Hans Naarding, observed what he believed to be a Thylacine for three minutes during the night at a site near Arthur River in northwestern Tasmania. The sighting led to an extensive year-long government-funded search.[71]

In January 1995, a Parks and Wildlife officer reported observing a thylacine in the Pyengana region of northeastern Tasmania in the early hours of the morning. Later searches revealed no trace of the animal.[72]

In 1997, it was reported that locals and missionaries near Mount Carstensz in Western New Guinea[73][74] had sighted thylacines. The locals had apparently known about them for many years but had not made an official report.[75]

In February 2005 Klaus Emmerichs, a German tourist, claimed to have taken digital photographs of a Thylacine he saw near the Lake St Clair National Park, but the authenticity of the photographs has not been established.[76] The photos were not published until April 2006, fourteen months after the sighting. The photographs, which showed only the back of the animal, were said by those who studied them to be inconclusive as evidence of the Thylacine’s continued existence.[77]

Rewards

In 1983, Ted Turner offered a $100,000 reward for proof of the continued existence of the Thylacine.[78] However, a letter sent in response to an inquiry by a thylacine-searcher, Murray McAllister, in 2000 indicated that the reward had been withdrawn.[79]

In March 2005, Australian news magazine The Bulletin, as part of its 125th anniversary celebrations, offered a $1.25 million reward for the safe capture of a live thylacine. When the offer closed at the end of June 2005 no one had produced any evidence of the animal’s existence. An offer of $1.75 million has subsequently been offered by a Tasmanian tour operator, Stewart Malcolm.[77]

Trapping is illegal under the terms of the thylacine’s protection, so any reward made for its capture is invalid, since a trapping licence would not be issued.

Modern research and projects

Records of all specimens, many of which are in European collections, are now held in the International Thylacine Specimen Database. The Australian Museum in Sydney began a cloning project in 1999.[80] The goal was to use genetic material from specimens taken and preserved in the early 20th century to clone new individuals and restore the species from extinction. Several microbiologists have dismissed the project as a public relations stunt and its chief proponent, Professor Mike Archer, received a 2002 nomination for the Australian Skeptics Bent Spoon Award for "the perpetrator of the most preposterous piece of paranormal or pseudo-scientific piffle".[81]

In late 2002 the researchers had some success as they were able to extract replicable DNA from the specimens.[82] On 15 February 2005, the museum announced that it was stopping the project after tests showed the DNA retrieved from the specimens had been too badly degraded to be usable.[83][84]

In May 2005, Professor Michael Archer, the University of New South Wales Dean of Science, former director of the Australian Museum and evolutionary biologist, announced that the project was being restarted by a group of interested universities and a research institute.[77][85]

The International Thylacine Specimen Database was completed in April 2005 and is the culmination of a four-year research project to catalog and digitally photograph, if possible, all known[57][86] surviving Thylacine specimen material held within museum, university and private collections. The master records are held by the Zoological Society of London.[2]

In 2008 researchers Andrew J. Pask and Marilyn B. Renfree from the University of Melbourne and Richard R. Behringer from the University of Texas reported that they managed to restore functionality of a gene Col2A1 enhancer obtained from 100 year-old ethanol-fixed thylacine tissues from museum collections. The genetic material was found working in transgenic mice. The research enhanced hopes of eventually restoring the population of thylacines.[87][88]

That same year, another group of researchers successfully sequenced the complete thylacine mitochondrial genome from two museum specimens. Their success suggests that it may be feasible to sequence the complete thylacine nuclear genome from museum specimens. Their results were published in the journal Genome Research in 2009.