The Underdevelopment of European Pride

Source: eurocanadian.ca

The most powerful moral assault on European pride and identity is the idea that Western civilization achieved its greatness, industrial economic take-off in the eighteenth century, and subsequent mass affluence in the twentieth century, by exploiting and under-developing the rest of the world. This is one of the biggest lies inflicted on millions of European students in the last half century. The truth is that the diffusion of European technology has been the ultimate factor responsible for development outside the West.

Stolen Land and the Atlantic Slave Trade

The claim that whites built modern America, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia by "stealing" the land from the original inhabitants, dehumanizing them and sequestering them into reservations, has exacted an enormous moral price upon Europeans. Europeans are a high trust people who believe it is important to treat others fairly as individuals regardless of in-group vs out-group distinctions — unlike other races, which tend to care only about their extended family members within the moral boundaries set by their in-groups. Our hostile elites have exploited this sense of fairness to make Europeans feel guilty about everything their ancestors did in the past. Not a month goes by without a headline that whites "should return stolen lands to Indian tribes."

Another claim intended to inflict guilt is that Europeans "deliberately" introduced slavery into Africa, rather than making use of a millennial practice, disrupting the "normal" economic activities of Africans and trapping them into vicious inter-tribal wars over slaves to be sold to rapacious whites. This story has been recounted in hundreds of books and journals singularly focused on slavery.

Not only blamed for the poverty of others, but others have been morally elevated as the ones responsible for the achievements of Europeans. One of the most influential books in this respect was Eric Williams's Capitalism and Slavery (1944), which argued that an inequitable "triangular trade" pattern, based on the slave trade and the production of "colonial goods in American plantations, played a "critical role" in British industrialization. The British would not have been able to pay for new industrial technologies were it not for the huge profits they obtained from the selling of slave-produced "tropical goods" such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton to European consumers.

How about the Arab Sex Slave Trade in White Women?

It does not matter that economic calculations would demonstrate that the total sums of money invested by slave traders in the process of industrialization amounted to less than 1% of the total capital invested during the key period of industrialization between 1760 and 1810, as was argued by Roger Anstey in his extensive 456 page book, The Atlantic slave trade and British abolition, 1760-1810 (1975). This book is now a blanc space in the internet, whereas Williams's 1944 thesis remains sacrosanct in academia, elaborated, celebrated, and imitated a thousand fold.

The role that millions of British farmers and workers played, together with British institutions, with their greater protection of property rights, openness to merit, including the unsurpassed presence in Britain of numerous schools and societies dedicated to the application of scientific ideas, were somehow not "crucial" but parasitic on the hard work of Africans in the Americas. How could so many academics believe that a transformation, the industrial revolution, so uniquely dependent on scientific knowledge, favourable institutions, and a population with aptitudes, foresight, frugality, and devotion to hard work — components never found before in unison — was made possible by slavery, a typical feature found in numerous societies throughout history, none of which industrialized?

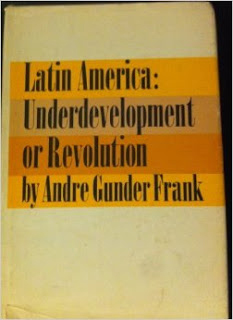

Andre Gunder Frank

But the effort to inflict moral culpability on Europeans would not be restricted to their past historical actions. It was argued with increasing intensity from the 1960s on that the current prosperity Europeans and North Americans were enjoying was being made possible through their control of a capitalist world economic order systematically engaged in the exploitation of "peripheral" non-white nations. The most important advocate of this idea was the Jewish émigré Andre Gunder Frank (1929-2005), starting with his two books, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America (1967), and Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution (1969). These books spearheaded Frank into international fame only a rare few academics ever attain, with countless visiting professorships and seminars at dozens of universities around the world, active involvement in leftist politics in Latin America, and numerous honours, most recently "the Andre Gunder Frank Memorial Library" at the Art Nouveau building of the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga.

The backwardness of Latin America, Frank insisted, was not due to to a supposedly feudal subsistence economy; on the contrary, Latin America was capitalist from the moment it was incorporated into a European dominated world market in the sixteenth century. This world market entailed a situation in which Latin Americans suffered a balance of payments deficit, resulting in the continuous transfer of a "surplus" from "satellite" nations to "metropolitan" European nations. This surplus transfer provided the capital necessary for the development of European nations at the cost of the "underdevelopment" of Latin America. Whites were still benefiting from this system of exploitation in the twentieth century. The slave plantations, the mineral mines of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the "free trade" deals of the nineteenth century, and the multinationals of the current era, were all equally exploitative, employing different mechanisms of surplus extraction through the same process of capitalistic exploitation.

Frank would come up with a very effective phrase to inflict guilt on prosperous nations: "the development of underdevelopment". Western nations only developed, and continued to be wealthy, because they dominated a world economy characterized by the extraction of surplus from peripheral nations. The nations outside European lands were not "undeveloped", less developed than European nations, they were "under-developed" in the course of the last centuries. The nations of Europe were not really more advanced than non-European nations in the sixteenth century; rather, they became more advanced through the underdevelopment of the rest of the world. This process of "development of underdevelopment" was still going on in the twentieth century, and the only way for Third World peoples to ever achieve development was to bring about communist revolutions in their lands and "de-link" their economies from the Western capitalist order.

The white working classes could no longer be counted on to make Marxist revolutions; as it was, Lenin was already arguing in the early 1900s that the British, French, and German working classes were more interested in reforming capitalism than overthrowing it, because they were benefiting from the imperialist exploitation of non-European lands, becoming a "labour aristocracy". Frank and others would push this idea further to argue that Third World peoples would be the true revolutionary agents. There were complaints from "classical" Marxists who believed that true communist revolutions could only succeed in advanced capitalist nations facing the "contradictions" of "over production" and "falling rates of profit" Marx had written about. But there was no stopping those who were anchoring their ideas in actual movements of "national liberation" and "communist development" across the Third World during the 1960s and 1970s.

It did not matter that the British Marxist Bill Warren published an article in 1973, "Imperialism and Capitalist Industrialization," persuasively demonstrating, through detailed empirical data, that capitalist development was rapidly taking place in at least some Third World countries. Warren explained that even if remitted profits exceeded foreign investment, development was possible (and real) since economic change was generated "in between" the inward flow of investment and the outward flow of repatriated profits. This was plain economics, but Warren was immediately chastised for his inability to understand the nature of capitalism as an imperialistic system inherently exploitative and hierarchical; the "development" of the Third World was a mirage bedeviled by huge debts, authoritarian governments, and "disarticulated growth". Warren tried to elaborate his ideas into a book, only to die in 1978 with an unfinished manuscript, forgotten as a old white male with no business writing about Marxism.

...

Read the rest: eurocanadian.ca