The Unsolved Mystery of the Tunnels at Baiae

Source: blogs.smithsonianmag.com

There is nothing remotely Elysian about the Phlegræan Fields, which lie on the north shore of the Bay of Naples; nothing sylvan, nothing green. The Fields are part of the caldera of a volcano that is the twin of Mount Vesuvius, a few miles to the east, the destroyer of Pompeii. The volcano is still active–it last erupted in 1538, and once possessed a crater that measured eight miles across–but most of it is underwater now. The portion that is still accessible on land consists of a barren, rubble-strewn plateau. Fire bursts from the rocks in places, and clouds of sulfurous gas snake out of vents leading up from deep underground. Baiae and the Bay of Naples, painted by J.M.W. Turner in 1823, well before modernization of the area obliterated most traces of its Roman past. |

The Fields, in short, are hellish, and it is no surprise that in Greek and Roman myth they were associated with all manner of strange tales. Most interesting, perhaps, is the legend of the Cumæan sibyl, who took her name from the nearby town of Cumæ, a Greek colony dating to about 500 B.C.– a time when the Etruscans still held sway much of central Italy and Rome was nothing but a city-state ruled over by a line of tyrannical kings.

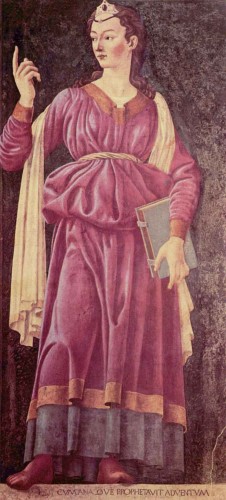

A Renaissance-era depiction of a young Cumæan sibyl by Andrea del Catagno. The painting can be seen in the Uffizi Gallery. |

The sibyl, so the story goes, was a woman named Amalthaea who lurked in a cave on the Phlegræan Fields. She had once been young and beautiful–beautiful enough to attract the attentions of the sun god, Apollo, who offered her one wish in exchange for her virginity. Pointing to a heap of dust, Amalthaea asked for a year of life for each particle in the pile, but (as is usually the way in such old tales) failed to allow for the vindictiveness of the gods. Ovid, in Metamorphoses, has her lament that “like a fool, I did not ask that all those years should come with ageless youth, as well.” Instead, she aged but could not die. Virgil depicts her scribbling the future on oak leaves that lay scattered about the entrance to her cave, and states that the cave itself concealed an entrance to the underworld.

The best-known–and from our perspective the most interesting–of all the tales associated with the sibyl is supposed to date to the reign of Tarquinius Superbus–Tarquin the Proud. He was the last of the mythic kings of Rome, and some historians, at least, concede that he really did live and rule in the sixth century B.C. According to legend, the sibyl traveled to Tarquin’s palace bearing nine books of prophecy that set out the whole of the future of Rome. She offered the set to the king for a price so enormous that he summarily declined–at which the prophetess went away, burned the first three of the books, and returned, offering the remaining six to Tarquin at the same price. Once again, the king refused, though less arrogantly this time, and the sibyl burned three more of the precious volumes. The third time she approached the king, he thought it wise to accede to her demands. Rome purchased the three remaining books of prophecy at the original steep price.

What makes this story of interest to historians as well as folklorists is that there is good evidence that three Greek scrolls, known collectively as the Sibylline Books, really were kept, closely guarded, for hundreds of years after the time of Tarquin the Proud. Secreted in a stone chest in a vault beneath the Temple of Jupiter, the scrolls were brought out at times of crisis and used, not as a detailed guide to the future of Rome, but as a manual that set out the rituals required to avert looming disasters. They served the Republic well until the temple burned down in 83 B.C., and so vital were they thought to be that huge efforts were made to reassemble the lost prophecies by sending envoys to all the great towns of the known world to look for fragments that might have come from the same source. These reassembled prophecies were pressed back into service and not finally destroyed until 405, when they are thought to have been burned by a noted general by the name of Flavius Stilicho.

The existence of the Sibylline Books certainly suggests that Rome took the legend of the Cumæan sibyl seriously, and indeed the geographer Strabo, writing at about the time of Christ, clearly states that there actually was “an Oracle of the Dead” somewhere in the Phlegræan Fields. So it is scarcely surprising that archaeologists and scholars of romantic bent have from time to time gone in search of a cave or tunnel that might be identified as the real home of a real sibyl–nor that some have hoped that they would discover an entrance, if not to Hades, then at least to some spectacular subterranean caverns.

Sulfur drifts from a vent on the barren volcanic plateau known as the Phlegraean Fields, a harsh moonscape associated with legends of prophecy.

Over the years several spots, the best known of which lies close to Lake Avernus, have been identified as the antro della sibilla–the cave of the sibyl. None, though, leads to anywhere that might reasonably be confused with an entrance to the underworld. Because of this, the quest continued, and gradually the remaining searchers focused their attentions on the old Roman resort of Baiæ (Baia), which lies on Bay of Naples at a spot where the Phlegræan Fields vanish beneath the Tyrrhenian Sea. Two thousand years ago, Baiæ was a flourishing spa, noted both for its mineral cures and for the scandalous immorality that flourished there. Today, it is little more than a collection of picturesque ruins–but it was there, in the 1950s, that the entrance to a hitherto unknown antrum was discovered by the Italian archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri. It had been concealed for years beneath a vineyard; Maiuri’s workers had to clear a 15-foot-thick accumulation of earth and vines.

The antrum at Baiæ proved difficult to explore. A sliver of tunnel, obviously ancient and manmade, disappeared into a hillside close to the ruins of a temple. The first curious onlookers who pressed their heads into its cramped entrance discovered a pitch-black passageway that was uncomfortably hot and wreathed in fumes; they penetrated only a few feet into the interior before beating a hasty retreat. There the mystery rested, and it was not revived until the site came to the attention of Robert Paget in the early 1960s.

Paget was not a professional archaeologist. He was a Briton who worked at a nearby NATO airbase, lived in Baiæ, and excavated mostly as a hobby. As such, his theories need to be viewed with caution, and it is worth noting that when the academic Papers of the British School at Rome agreed to publish the results of the decade or more that he and an American colleague named Keith Jones spent digging in the tunnel, a firm distinction was drawn between the School’s endorsement of a straightforward description of the findings and its refusal to pass comment on the theories Paget had come up with to explain his perplexing discoveries. These theories eventually made their appearance in book form but attracted little attention–surprisingly, because the pair claimed to have stumbled across nothing less than a real-life “entrance to the underworld.”

Paget was one of the handful of men who still hoped to locate the “cave of the sibyl” described by Virgil, and it was this obsession that made him willing to risk the inhospitable interior. He and Jones pressed their way though the narrow opening and found themselves inside a high but narrow tunnel, eight feet tall but just 21 inches wide. The temperature inside was uncomfortable but bearable, and although the airless interior was still tinged with volcanic fumes, the two men pressed on into a passage that, they claimed, had probably not been entered for 2,000 years.

[...]

Read the full article at: smithsonianmag.com