What’s next for NASA’s LCROSS moon-crashing mission

Source: usatoday.com

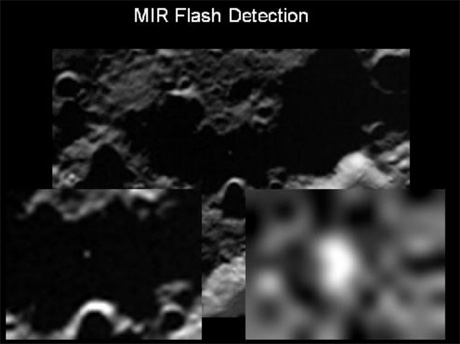

This mid-infrared image was taken in the last minutes of the LCROSS flight mission to the Moon. The small white spot (enlarged in the insets) seen within the dark shadow of lunar crater walls is the initial flash created by the impact of a spent Centaur upper stage rocket.

Traveling at 1.5 miles per second, the Centaur rocket hit the lunar surface yesterday at 4:31am UT, followed a few minutes later by the shepherding LCROSS spacecraft. Earthbound observatories have reported capturing both impacts. But before crashing into the lunar surface itself, the LCROSS spacecraft’s instrumentation successfully recorded close-up the details of the rocket stage impact, the resulting crater, and debris cloud. In the coming weeks, data from the challenging mission will be used to search for signs of water in the lunar material blasted from the surface.

Image from: spacefellowship.com

Once you’ve dug yourself into a hole, stop digging. Or if you’re NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) team, take a nap.

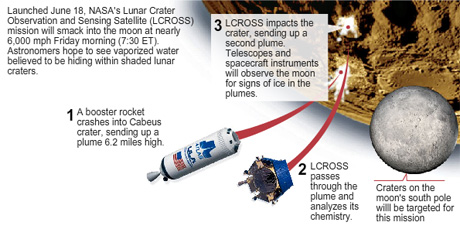

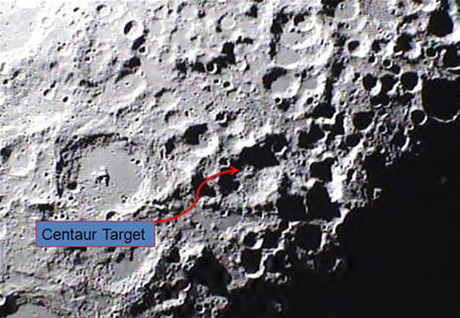

Friday morning’s excitement — blasting a lunar crater with twin 6,000 mile-per-hour impacts — left the LCROSS controller team dead on its feet, says NASA’s Grey Hautaluoma. Meanwhile, the science team is frantically looking into observations flowing from telescopes, spacecraft and the LCROSS "shepherd" vehicle, which caught sight of its booster’s 7:31 a.m. ET impact crater, before plowing into the Cabeus crater on the moon’s South Pole itself, four minutes later.

"We just slammed something the size of a school bus into the moon going really fast. It was a lunar encounter of the hardest kind," says LCROSS team scientist Peter Schultz of Brown University, an expert on crater impacts. "Everyone’s happy, but it’s hard to be excited after you’ve been up 36 hours straight, (so) a lot of the mission team is grabbing some rest."

In a post-impact briefing Friday morning at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., questioners expressed disappointment that the impacts hadn’t thrown up a dramatic cloud over the moon’s South Pole, noting the $79 million mission’s goal was to create plumes of moon dust, hopefully filled with ice, for analysis.

"I think that’s reporters just getting over-excited after writing about us ’bombing the moon,’ the last few days," Schultz says. (I plead guilty.) "What we saw actually looks like one of the options we discussed and saw in lab experiments."

At the briefing, LCROSS project scientist Anthony Colaprete outlined several reasons why the impacts may not have thrown up plumes immediately visible after the impacts, including the booster and spacecraft hitting the inner walls of the crater at an angle that ejected the impact pit dust sideways instead of straight up. "Luck plays a part in this," he said, adding. "We have the data we need to address the questions we have and that’s the bottom line."

Most important, the shepherd spacecraft caught sight of a flash from the crater made by its booster, Colaprete noted, estimating that pit’s width at about 60 feet across, based on that glimpse.

"That flash was very important," Schultz says. "That means we have heat." Heat means whatever dust was tossed up by the impact was baked, which should reveal its chemistry to the spectroscopes observing the event. Readings from a photometer (which records the brightness and duration of the impact flash) aboard the shepherd spacecraft, which Schultz hinted looked promising, should enable the team to tell whether LCROSS hit solid rock or powdery lunar soil.

The whole point of the mission is to see whether ice, perhaps left over from comet impacts billions of years ago, lingers in the shaded craters on the moon’s poles. Lunar explorers might drink that water, or extract hydrogen from water for use as rocket fuel, someday, if it’s there in meaningful amounts.

"Of course, we’d like to see buckets of watery ice," Schultz says. But the science team, "has to be very careful," because any signatures of water reported by instruments has to be measured against carefully calibrated standards. "We’re comparing one thing against another, not measuring it directly, so we have to be certain all the calibrations are absolutely right, so we don’t get a false positive."

The LCROSS impact comes as planetary scientists are re-evaluating the moon’s watery potential. NASA’s Lunar Prospector mission in 1999 showed signs of unexpected water deposits in the lunar polar craters. And last month, Science magazine reported evidence that solar wind’s particles are releasing tiny amounts of water from the moon’s soil all the time, a big change from the era of the 1970’s moon landings.

"The general feeling after Apollo was that the moon is very dry," says William Hartmann of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson.

Hartmann and a colleague proposed the idea three decades ago, now generally accepted in planetary science, that the moon started after a Mars-sized proto-planet struck the early Earth’s northern hemisphere around 4.5 billion years ago. The debris from the blast swirled around the Earth in a ring for hundreds of thousands of years — baking away any water it was thought — before balling up into the moon, an idea inspired by the moon rock findings.

"As soon as the lunar rocks arrived on Earth, researchers found the moon is basically very dry. The rocks don’t have large amounts of hydrated minerals, clays, or other minerals that indicate exposure to water," Hartmann says. "That finding seems to be still basically true, of rocks at depth on the moon, beneath the surface layers."

Instead, the LCROSS results should show whether any comets, essentially oversized dirty snowballs, left any water behind when they hit the moon after its formation.

"The LCROSS impact produced a crater five times smaller than a football field and threw dust hundreds of feet into space," Schultz says. "A big billowing cloud, that’s just science fiction. This is reality, where what we are looking for is water molecules."

So, just like the mission controllers, you might want to sleep on instant results from the mission. Colaprete suggested definitive word won’t come until a December science meeting. "It’s now time to go to sleep and get ready to dig into the data, now that we’ve dug into the Moon," Schultz says.

Red Ice Radio

Alfred Webre - Exopolitics, NASA Bombing of the Moon, Outer Space Treaty & E.T.

Mike Bara - Dark Mission, The Occult NASA Moon Mission

Jim Marrs - The Secret Society Agenda, Alien or Human?