Abraham Lincoln Created The Secret Service The Day He Was Shot

Source: nowiknow.com

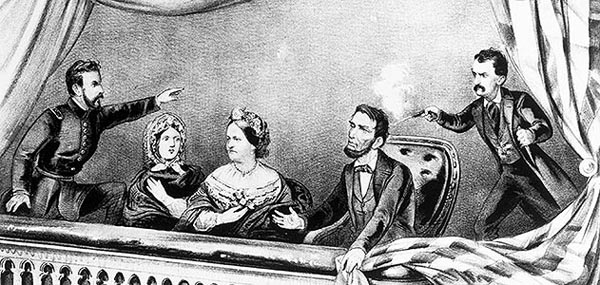

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. He’d die the next morning.

But also on April 14, 1865, Lincoln signed into law a piece of legislation which created the Secret Service — the law enforcement agency charged with defending the President from, among other things, assassination attempts such as the one that befell Lincoln that evening. Was Lincoln also a victim of bad timing? Perhaps he had ESP? Not really — rather, it’s a strange historical coincidence. While we currently think of the Secret Service as primarily existing to protect the President, that was not its original intent.

During the early to mid-1800s, roughly a third of American money was counterfeit. The solution was something similar to today’s approach to large scale problems — form a commission. On the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch, Lincoln did exactly that. The conclusion was to form a federal law enforcement division (at the time, there was no FBI), the “Secret Service of Division of the Department of the Treasury.” That Division was born just hours before John Wilkes Booth fatally shot the President.

The Secret Service carried out their Treasury duties, primarily, for the next 35 years. While Lincoln’s assassination sparked a discussion about the need for a permanent security detail for the President, this need went unfulfilled for decades. In the interim period, both James A. Garfield (1881) and William McKinley (1901) were assassinated. The latter caused Congress to work toward a solution, and, informally, Presidential security became a duty of the Service starting with McKinley’s successor, Theodore Roosevelt.

[...]

Read the full article at: nowiknow.com

Lincoln’s Missing Bodyguard

By Paul Martin| Smithsonian

When a celebrity-seeking couple crashed a White House state dinner last November, the issue of presidential security dominated the news. The Secret Service responded by putting three of its officers on administrative leave and scrambled to reassure the public that it takes the job of guarding the president very seriously. “We put forth the maximum effort all the time,” said Secret Service spokesman Edwin Donovan.

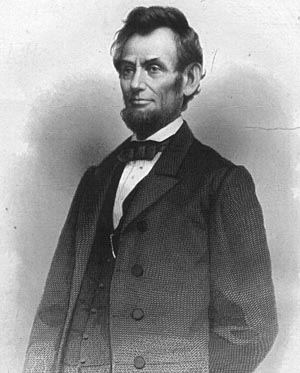

That kind of dedication to safeguarding the president didn’t always exist. It wasn’t until 1902 that the Secret Service, created in 1865 to eradicate counterfeit currency, assumed official full-time responsibility for protecting the president. Before that, security for the president could be unbelievably lax. The most astounding example was the scant protection afforded Abraham Lincoln on the night he was assassinated. Only one man, an unreliable Washington cop named John Frederick Parker, was assigned to guard the president at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865.

Today it’s hard to believe that a single policeman was Lincoln’s only protection, but 145 years ago the situation wasn’t that unusual. Lincoln was cavalier about his personal safety, despite the frequent threats he received and a near-miss attempt on his life in August 1864, as he rode a horse unescorted. He’d often take in a play or go to church without guards, and he hated being encumbered by the military escort assigned to him. Sometimes he walked alone at night between the White House and the War Department, a distance of about a quarter of a mile.

John Parker was an unlikely candidate to guard a president—or anyone for that matter. Born in Frederick County, Virginia, in 1830, Parker moved to Washington as a young man, originally earning his living as a carpenter. He became one of the capital’s first officers when the Metropolitan Police Force was organized in 1861. Parker’s record as a cop fell somewhere between pathetic and comical. He was hauled before the police board numerous times, facing a smorgasbord of charges that should have gotten him fired. But he received nothing more than an occasional reprimand. His infractions included conduct unbecoming an officer, using intemperate language and being drunk on duty. Charged with sleeping on a streetcar when he was supposed to be walking his beat, Parker declared that he’d heard ducks quacking on the tram and had climbed aboard to investigate. The charge was dismissed. When he was brought before the board for frequenting a whorehouse, Parker argued that the proprietress had sent for him.

In November 1864, the Washington police force created the first permanent detail to protect the president, made up of four officers. Somehow, John Parker was named to the detail. Parker was the only one of the officers with a spotty record, so it was a tragic coincidence that he drew the assignment to guard the president that evening. As usual, Parker got off to a lousy start that fateful Friday. He was supposed to relieve Lincoln’s previous bodyguard at 4 p.m. but was three hours late.

Lincoln’s party arrived at the theater at around 9 p.m. The play, Our American Cousin, had already started when the president entered his box directly above the right side of the stage. The actors paused while the orchestra struck up “Hail to the Chief.” Lincoln bowed to the applauding audience and took his seat.

Parker was seated outside the president’s box, in the passageway beside the door. From where he sat, Parker couldn’t see the stage, so after Lincoln and his guests settled in, he moved to the first gallery to enjoy the play. Later, Parker committed an even greater folly: At intermission, he joined the footman and coachman of Lincoln’s carriage for drinks in the Star Saloon next door to Ford’s Theatre.

John Wilkes Booth entered the theater around 10 p.m. Ironically, he’d also been in the Star Saloon, working up some liquid courage.

[...]

Read the full article at: smithsonianmag.com