Our Ancestors, the Acoustical Engineers

Source: discovermagazine.com

Ancient builders designed subterranean soundscapes as stirring as any special effect.

When priests at the temple complex of Chavín de Huántar in central Peru sounded their conch-shell trumpets 2,500 years ago, tones magnified and echoed by stone surfaces seemed to come from everywhere, yet nowhere. The effect must have seemed otherworldly, but there was nothing mysterious about its production. According to archaeologists at Stanford University, the temple’s builders created galleries, ducts, and ventilation shafts to channel sound. In short, the temple’s designers may have been not only expert architects but also skilled acoustical engineers.

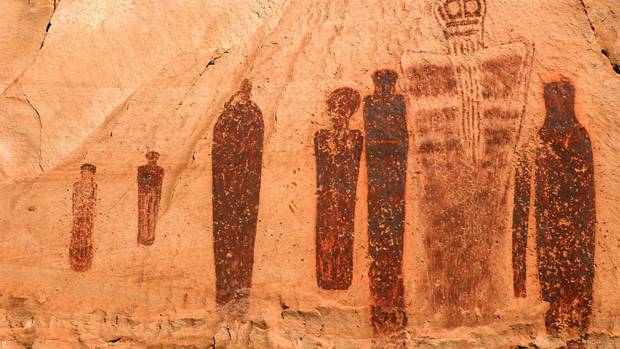

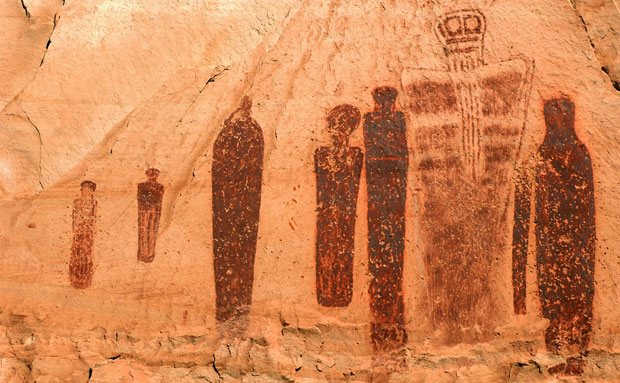

The 4,000 year-old pictographs at Horseshoe Canyon in Utah may have been inspired by the spectacular acoustics there.

The findings add to a growing body of research suggesting that sound meant more to our ancestors than archaeologists once realized. We live in a sound-saturated society, full of iPods, thunderous special effects in movies, and thousand-watt car stereos. New discoveries in the young field of acoustic archaeology hint that just as we create elaborate sonic environments with our electronics, the ancients may have sculpted their soundscapes as well. Like many artistic endeavors, their efforts may have been rooted in an attempt to reach the divine.

Portals to the Spirit Worlds

Some of the first research on the importance of acoustics to prehistoric peoples was done by Iegor Reznikoff, an anthropologist of sound at Université Paris Ouest, who in the 1980s visited cave paintings and carvings in southern France that are about 25,000 years old, among the oldest known human art. A number of them are so far underground that scientists were puzzled as to why anyone would have gone there. Reznikoff, who has a habit of humming whenever he enters a space, noticed that in parts of the caves, his voice resonated as effectively as in any cathedral. He and a colleague mapped several caves and found that areas with the greatest resonance coincided with the concentration of artworks.

Further evidence for the connection between art and sound came from Steven J. Waller, a biochemist and avocational archaeologist from California. Waller knew that echoes played a role in many ancient myths, such as Native American tales of sprites who speak through portals in rock walls. In 1994 he conducted an acoustical survey of Horseshoe Canyon, a three-mile-long chasm in southeastern Utah decorated with eerie pictographs. Waller hiked the canyon, pausing at 80 locations to snap a noisemaker fashioned from a rat trap and record the echoes. After processing the results with sound analysis software, he found that five spots displayed powerful echo effects. Four corresponded to the locations of paintings that Waller had encountered. When he asked experts about the fifth, they explained that it, too, bore artwork, though the pictographs were not visible from the path he had followed. Since then, Waller has repeated the experiment at hundreds of rock art sites around the world, almost always finding a correlation between image and echo. He speculates that ancient artists “purposely chose these places because of sound.”

Such findings suggest that ancient people created artworks in response to acoustics; others hint that they may even have built structures to control it. For example, El Castillo pyramid in Mexico, built by the Mayans some 1,100 years ago, bears four stepped sides, each vertically bisected by a staircase. If you clap your hands at the pyramid’s base, you hear a series of chirps. Locals near similar pyramids have long compared the sound to the cry of the quetzal, a bird venerated by the Mayans. In the 1990s acoustician David Lubman recorded the hand-clap echoes at El Castillo and compared them with recordings of the quetzal. He found that recordings and sonograms of several echoes really do match the bird’s cry. Lubman says the echo “is a powerfully robust phenomenon” unlikely to have resulted by accident.

Peru’s Temple of Sound Effects

The most detailed evidence of ancient acoustical design comes from the Stanford team studying Chavín de Huántar, which was constructed between 1300 and 500 B.C. Peruvian archaeologists first suspected the complex had an auditory function in the 1970s, when they found that water rushing through one of its canals mimicked the sound of roaring applause. Then, in 2001, Stanford anthropologist John Rick discovered conch-shell trumpets, called pututus, in one of the galleries. The team set out to determine what role the horns played in ancient rituals and how the temple may have heightened their effects. Archaeoacoustics researcher Miriam Kolar and her collaborators played computer-generated sounds to identify which frequencies the temple most readily transmits. Over years of experiments, they found that certain ducts enhanced the frequencies of the pututus while filtering out others, and that corridors amplified the trumpets’ sound. “It suggests the architectural forms had a special relationship to how sound is transmitted,” Kolar says. The researchers also had volunteers stand in one part of the temple while pututu recordings played in another. In some configurations, the sound seemed to come from all directions.

[...]

Read the full article at: discovermagazine.com

Mind-Altering Maze?

The Maya apparently weren’t the only ancient Americans to use architecture to manipulate sound, another research team suggests.

In the Peruvian Andes, for instance, a stony underground maze may have been designed not only to amplify sound but to disorient minds.

Beneath Chavín de Huántar, a 3,000-year old ceremonial center that predates the Inca, lies a roughly half-mile-long (one-kilometer-long) complex of underground rooms and twisty corridors, all connected by air ducts.

While excavating the so-called Gallery of the Labyrinths, researchers noticed that the galleries played strange acoustic tricks with the human voice and with sounds made by instruments discovered at Chavín, including marine-shell trumpets that create an animal-like roar when blown.

"If you walk and talk in the galleries, you hear your voice changing as you go through," said archaeologist John Rick, who also presented his team’s findings at the acoustics meeting.

"You don’t have to do a research project to know something strange is going on," said Rick, of Stanford University.

For example, some rooms and their interconnected spaces multiply echoes and bounce them back at listeners so rapidly that sounds appear to emanate from every direction at once, Rick’s team found.

"The sound reflects very rapidly from all the different surfaces of the stone, which is very irregular," said team member Miriam Kolar, a researcher at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research and Acoustics.

The effect, as well as the complicated floor plan, can be so disconcerting and disorienting that the team speculates the labyrinth was intentionally designed to confuse people inside.

Psychoactive drugs may also have been used to heighten the effect, based on evidence at Chavín. For example, stone sculptures seem to show people in the maze transforming into animal-like deities with the aid of drugs.

Source: National Geographic

Chavín de Huántar, Peru

Tune into Red Ice Radio:

Alex Putney - Messages of Resonance Change in 2012, Betelgeuse & Modern Alchemy

Alex Putney - Human Resonance, Sacred Sites, Pyramids & Standing Waves

Christopher Dunn - The Giza Power Plant & The Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt

Hugh Newman - The Olmecs & Megalithic Cultures

Hugh Newman - Earth Grids, Earth Energy, Megaliths & Sacred Sites

Daniel Tatman - The Bath Mystery’s: Architecture

Freddy Silva - Ancient Sacred Sites, Invisible Temples, Giants & Our Ancestors