Out-of-body experience: Master of illusion

Source: nature.com

It is not every day that you are separated from your body and then stabbed in the chest with a kitchen knife.

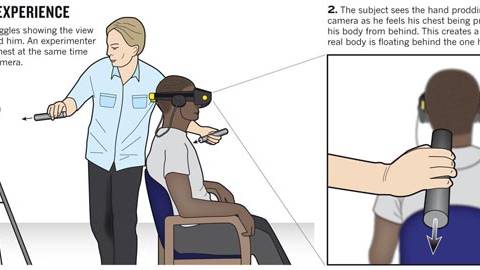

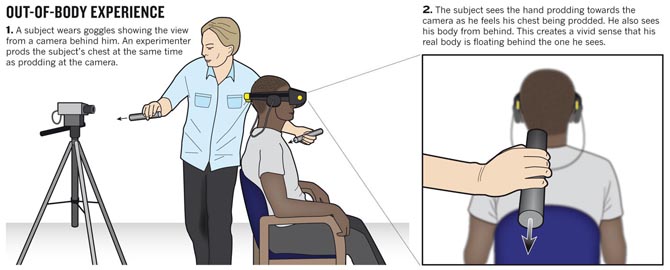

But such experiences are routine in the lab of Henrik Ehrsson, a neuroscientist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, who uses illusions to probe, stretch and displace people’s sense of self. Today, using little more than a video camera, goggles and two sticks, he has convinced me that I am floating a few metres behind my own body. As I see a knife plunging towards my virtual chest, I flinch. Two electrodes on my fingers record the sweat that automatically erupts on my skin, and a nearby laptop plots my spiking fear on a graph.

Out-of-body experiences are just part of Ehrsson’s repertoire. He has convinced people that they have swapped bodies with another person1, gained a third arm2, shrunk to the size of a doll or grown to giant proportions3. The storeroom in his lab is stuffed with mannequins of various sizes, disembodied dolls’ heads, fake hands, cameras, knives and hammers. It looks like a serial killer’s basement. “The other neuroscientists think we’re a little crazy,” Ehrsson admits.

But Ehrsson’s unorthodox apparatus amount to more than cheap trickery. They are part of his quest to understand how people come to experience a sense of self, located within their own bodies. The feeling of body ownership is so ingrained that few people ever think about it — and those scientists and philosophers who do have assumed that it was unassailable.

“Descartes said that if there’s something you can be certain of in this world, it’s that your hand is your hand,” says Ehrsson. Yet Ehrsson’s illusions have shown that such certainties, built on a lifetime of experience, can be disrupted with just ten seconds of visual and tactile deception. This surprising malleability suggests that the brain continuously constructs its feeling of body ownership using information from the senses — a finding that has earned Ehrsson publications in Science and other top journals, along with the attention of other neuroscientists.

“A lot of people thought the sense of self was hard-wired, but it’s not at all. It can be changed very quickly, and that’s very intriguing,” says Miguel Nicolelis, a neurobiologist at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina.

Ehrsson’s work also intrigues neuroscientists and philosophers because it turns a slippery, metaphysical construct — the self — into something that scientists can dissect. “We can say if we wobble the signals this way, our conscious experience wobbles in this way,” says David Eagleman, a neuroscientist who studies perception at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “That’s a lever we didn’t have before.”

“There are things like selfhood that people think cannot be touched by the hard sciences,” says Thomas Metzinger, director of the Theoretical Philosophy Group at Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany. “They are now demonstrably tractable. That’s what I think is valuable about Henrik’s contribution.”

Daydream Believer

Ehrsson was born in 1972 in a suburb of Stockholm. His father was a chemist, his grandfather a dentist, and both stoked an interest in science and the human body that led him to study medicine at the Karolinska Institute. But in long anatomy classes, Ehrsson often found himself bored. “During lectures, I kept on thinking that if my eyes were floating over there and I was looking at myself from that perspective, where would my consciousness be?” After a pause: “I was not an A student.”

After graduating, Ehrsson left medicine to start a PhD at the Karolinska, using brain scanners to study how people grasp objects. At the same time, he was becoming deeply fascinated by physical illusions. Some of these are well established: Aristotle discovered that crossing the index and middle fingers and touching the nose can — in some people — create a feeling of having two noses. Ehrsson also heard about the rubber-hand illusion, a trick devised in the late 1990s by researchers in the United States. They could convince people that a fake hand was their own by hiding their real hand under a table, placing a rubber one in front of them, and stroking both in the same way4. “It really worked on me,” Ehrsson says. “It was fantastic and surreal.”

Ehrsson started investigating illusions on the side. By the time he completed his postdoc at University College London and returned to the Karolinska Institute to start his own lab, illusions had become his main focus. He knew that many scientists use visual illusions to glean the basics of perception. “There are conferences on visual illusions, and yearly contests to create the best new ones,” he says. “But there aren’t many body illusions. The body has never been a main focus of psychology.” It was these tricks, such as the rubber-hand illusion, that Ehrsson was keen to explore. He wanted to test how easily the sense of body ownership could be distorted.

Ehrsson set about creating more illusions based on the same principles as the rubber hand one. Headsets, cameras or fake body parts fooled the eyes, and synchronous strokes and prods added a tactile clincher. In 2007, he reported that he had used such props to convince subjects that they had left their own bodies5 — a stunt that attracted headlines around the world.

The third arm illusion. Stroking my real arm in time with the middle (rubber) one, convinced me that the rubber one was mine. Ed Yong

At the time, some scientists and members of the public were openly sceptical that the illusion really worked. But on a trip to Ehrsson’s lab this September, I was convinced. The goggles I wore displayed the view from a camera pointing at my back. Ehrsson tapped my chest with one plastic rod while using a second one to synchronously prod at the camera. I saw and felt my chest being prodded at the same time as I saw a picture of myself from behind. Within ten seconds, I felt as if I was being pulled out of my real body and was floating several feet behind it.

A year after removing his subjects from their own bodies, Ehrsson learned how to trick them into acquiring new ones. This time, the volunteers’ goggles showed them the view from a camera on the head of a mannequin looking at its own plastic torso. Simultaneously poking the arm or stomach of the mannequin and the volunteer a few times was enough to convince the subjects that they were the dummy. They could even stare at their old bodies from their new ones and shake hands with their old self, all without breaking the spell. “It really is very intense and incredibly fast,” says Mark Hallett, a neurologist from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, who experienced it first hand.

In his latest trick, published in May3, Ehrsson convinced people that they had jumped into a tiny Barbie doll. When he prodded the doll’s legs, the volunteers thought they were being prodded by giant objects. And when Ehrsson tested the illusion on himself and a colleague touched his cheek, he says, he looked up and “felt as if I was back in my childhood and looking at my mother”.

Not everyone succumbs. Ehrsson suspects that people who can expertly localize their limbs without sight, such as dancers or musicians, would be less susceptible than the students with whom he normally works. But typically, the illusions work for around four out of five people. Ehrsson confirms the effects by asking his volunteers about their experiences and by threatening their disembodied, shrunken or plastic forms with a knife. If the illusion has worked, then volunteers show a reflexive burst of nervous sweating (as I did). Even knowing the knife is coming is no defence: as Ehrsson puts it, the illusions are “cognitively impregnable”.

Earlier this year, Ehrsson even tweaked the rubber-hand illusion and convinced people they owned a third hand2. “He has taken those basic ideas and investigated how far you can push them,” says neuroscientist Matthew Botvinick, one of the creators of the rubber-hand illusion, at Princeton University in New Jersey. “He’s shown how extreme and how malleable the body representation can be.”

Self delusion

Ehrsson’s next challenge is to work out what these illusions reveal about the brain. According to textbook wisdom, people build up a perception of their bodies using ’proprioception’ — signals from the skin, muscles and joints that indicate the relative position of body parts. But Ehrsson’s illusions show that vision and touch are also a crucial part of the mix, and that the brain builds a sense of self by constantly compiling information from all these senses. Proprioception may be telling the brain that the body is seated in a chair, but the carefully timed vision and touch signals in Ehrsson’s illusion convince the brain that it is somewhere else entirely.

[...]

Read the full article at: nature.com

This cookie’s taste is all in your head (Video)

Red Ice Radio:

George Kavassilas - Hour 1 - The Pending Global Mind Control Event

Lindy Cowling - Hour 1 - Heart Energy & Changes in Mass Consciousness

Penney Peirce - Frequency, Intuition, Time & Dreams

Anthony Peake & Tom Campbell - Consciousness Creates Reality

Anthony Peake - Mystery of the Brain, Precognition, Time Dilation & Déjà vu

Marcel Kuijsten - Julian Jaynes, the Bicameral Mind & The Origin of Consciousness

Jim Elvidge - Are we Living in a Simulation, a Programmed Reality?