The internet: is it changing the way we think?

Source: guardian.co.uk

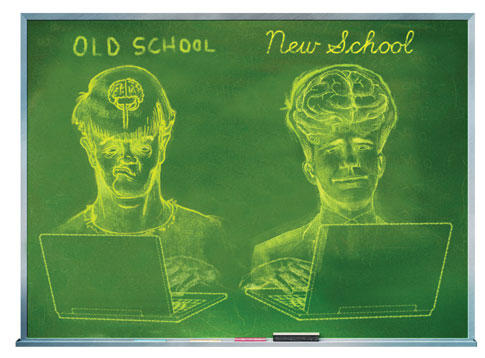

Are our minds being altered due to our increasing reliance on search engines, social networking sites and other digital technologies?

Every 50 years or so, American magazine the Atlantic lobs an intellectual grenade into our culture. In the summer of 1945, for example, it published an essay by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) engineer Vannevar Bush entitled "As We May Think". It turned out to be the blueprint for what eventually emerged as the world wide web. Two summers ago, the Atlantic published an essay by Nicholas Carr, one of the blogosphere’s most prominent (and thoughtful) contrarians, under the headline "Is Google Making Us Stupid?".

"Over the past few years," Carr wrote, "I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going – so far as I can tell – but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle."

The title of the essay is misleading, because Carr’s target was not really the world’s leading search engine, but the impact that ubiquitous, always-on networking is having on our cognitive processes. His argument was that our deepening dependence on networking technology is indeed changing not only the way we think, but also the structure of our brains.

Carr’s article touched a nerve and has provoked a lively, ongoing debate on the net and in print (he has now expanded it into a book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains). This is partly because he’s an engaging writer who has vividly articulated the unease that many adults feel about the way their modi operandi have changed in response to ubiquitous networking. Who bothers to write down or memorise detailed information any more, for example, when they know that Google will always retrieve it if it’s needed again? The web has become, in a way, a global prosthesis for our collective memory.

It’s easy to dismiss Carr’s concern as just the latest episode of the moral panic that always accompanies the arrival of a new communications technology. People fretted about printing, photography, the telephone and television in analogous ways. It even bothered Plato, who argued that the technology of writing would destroy the art of remembering.

But just because fears recur doesn’t mean that they aren’t valid. There’s no doubt that communications technologies shape and reshape society – just look at the impact that printing and the broadcast media have had on our world. The question that we couldn’t answer before now was whether these technologies could also reshape us. Carr argues that modern neuroscience, which has revealed the "plasticity" of the human brain, shows that our habitual practices can actually change our neuronal structures. The brains of illiterate people, for example, are structurally different from those of people who can read. So if the technology of printing – and its concomitant requirement to learn to read – could shape human brains, then surely it’s logical to assume that our addiction to networking technology will do something similar?

Not all neuroscientists agree with Carr and some psychologists are sceptical. Harvard’s Steven Pinker, for example, is openly dismissive. But many commentators who accept the thrust of his argument seem not only untroubled by its far-reaching implications but are positively enthusiastic about them. When the Pew Research Centre’s Internet & American Life project asked its panel of more than 370 internet experts for their reaction, 81% of them agreed with the proposition that "people’s use of the internet has enhanced human intelligence".

Others argue that the increasing complexity of our environment means that we need the net as "power steering for the mind". We may be losing some of the capacity for contemplative concentration that was fostered by a print culture, they say, but we’re gaining new and essential ways of working. "The trouble isn’t that we have too much information at our fingertips," says the futurologist Jamais Cascio, "but that our tools for managing it are still in their infancy. Worries about ’information overload’ predate the rise of the web... and many of the technologies that Carr worries about were developed precisely to help us get some control over a flood of data and ideas. Google isn’t the problem – it’s the beginning of a solution."

Sarah Churchwell, academic and critic

Is the internet changing our brains? It seems unlikely to me, but I’ll leave that question to evolutionary biologists. As a writer, thinker, researcher and teacher, what I can attest to is that the internet is changing our habits of thinking, which isn’t the same thing as changing our brains. The brain is like any other muscle – if you don’t stretch it, it gets both stiff and flabby. But if you exercise it regularly, and cross-train, your brain will be flexible, quick, strong and versatile.

In one sense, the internet is analogous to a weight-training machine for the brain, as compared with the free weights provided by libraries and books. Each method has its advantage, but used properly one works you harder. Weight machines are directive and enabling: they encourage you to think you’ve worked hard without necessarily challenging yourself. The internet can be the same: it often tells us what we think we know, spreading misinformation and nonsense while it’s at it. It can substitute surface for depth, imitation for originality, and its passion for recycling would surpass the most committed environmentalist.

In 10 years, I’ve seen students’ thinking habits change dramatically: if information is not immediately available via a Google search, students are often stymied. But of course what a Google search provides is not the best, wisest or most accurate answer, but the most popular one.

But knowledge is not the same thing as information, and there is no question to my mind that the access to raw information provided by the internet is unparalleled and democratising. Admittance to elite private university libraries and archives is no longer required, as they increasingly digitise their archives. We’ve all read the jeremiads that the internet sounds the death knell of reading, but people read online constantly – we just call it surfing now. What they are reading is changing, often for the worse; but it is also true that the internet increasingly provides a treasure trove of rare books, documents and images, and as long as we have free access to it, then the internet can certainly be a force for education and wisdom, and not just for lies, damned lies, and false statistics.

In the end, the medium is not the message, and the internet is just a medium, a repository and an archive. Its greatest virtue is also its greatest weakness: it is unselective. This means that it is undiscriminating, in both senses of the word. It is indiscriminate in its principles of inclusion: anything at all can get into it. But it also – at least so far – doesn’t discriminate against anyone with access to it. This is changing rapidly, of course, as corporations and governments seek to exert control over it. Knowledge may not be the same thing as power, but it is unquestionably a means to power. The question is, will we use the internet’s power for good, or for evil? The jury is very much out. The internet itself is disinterested: but what we use it for is not.

Sarah Churchwell is a senior lecturer in American literature and culture at the University of East Anglia

Naomi Alderman, novelist

If I were a cow, nothing much would change my brain. I might learn new locations for feeding, but I wouldn’t be able to read an essay and decide to change the way I lived my life. But I’m not a cow, I’m a person, and therefore pretty much everything I come into contact with can change my brain.

It’s both a strength and a weakness. We can choose to seek out brilliant thinking and be challenged and inspired by it. Or we can find our energy sapped by an evening with a "poor me" friend, or become faintly disgusted by our own thinking if we’ve read too many romance novels in one go. As our bodies are shaped by the food we eat, our brains are shaped by what we put into them.

So of course the internet is changing our brains. How could it not? It’s not surprising that we’re now more accustomed to reading short-form pieces, to accepting a Wikipedia summary, rather than reading a whole book. The claim that we’re now thinking less well is much more suspect. If we’ve lost something by not reading 10 books on one subject, we’ve probably gained as much by being able to link together ideas easily from 10 different disciplines.

But since we’re not going to dismantle the world wide web any time soon, the more important question is: how should we respond? I suspect the answer is as simple as making time for reading. No single medium will ever give our brains all possible forms of nourishment. We may be dazzled by the flashing lights of the web, but we can still just step away. Read a book. Sink into the world of a single person’s concentrated thoughts.

Time was when we didn’t need to be reminded to read. Well, time was when we didn’t need to be encouraged to cook. That time’s gone. None the less, cook. And read. We can decide to change our own brains – that’s the most astonishing thing of all.

Ed Bullmore, psychiatrist

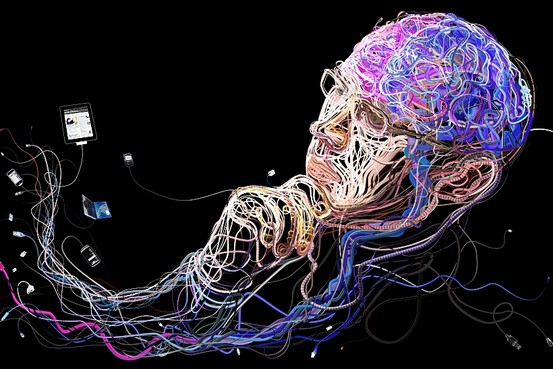

Whether or not the internet has made a difference to how we use our brains, it has certainly begun to make a difference to how we think about our brains. The internet is a vast and complex network of interconnected computers, hosting an equally complex network – the web – of images, documents and data. The rapid growth of this huge, manmade, information-processing system has been a major factor stimulating scientists to take a fresh look at the organisation of biological information-processing systems like the brain.

It turns out that the human brain and the internet have quite a lot in common. They are both highly non-random networks with a "small world" architecture, meaning that there is both dense clustering of connections between neighbouring nodes and enough long-range short cuts to facilitate communication between distant nodes. Both the internet and the brain have a wiring diagram dominated by a relatively few, very highly connected nodes or hubs; and both can be subdivided into a number of functionally specialised families or modules of nodes. It may seem remarkable, given the obvious differences between the internet and the brain in many ways, that they should share so many high-level design features. Why should this be?

One possibility is that the brain and the internet have evolved to satisfy the same general fitness criteria. They may both have been selected for high efficiency of information transfer, economical wiring cost, rapid adaptivity or evolvability of function and robustness to physical damage.Networks that grow or evolve to satisfy some or all of these conditions tend to end up looking the same.

Although there is much still to understand about the brain, the impact of the internet has helped us to learn new ways of measuring its organisation as a network. It has also begun to show us that the human brain probably does not represent some unique pinnacle of complexity but may have more in common than we might have guessed with many other information-processing networks.

...

Read the full article at: guardian.co.uk

Top Image: Source Credit: Charis Tsevis

New Evidence Suggests That Using the Internet Might Make You Smarter, Not Rot Your Brain

Also tune into:

Peter Russell - The Primacy of Consciousness

Peter Russell - Awareness, Presence & The Global Brain

Lynne McTaggart - The Intention Experiment

Bruce Lipton - The Biology of Belief

Dominick Ohrbeck - The HeartBrain Model

Joe Slate - Psychic Vampires, Energy Predators & Energy of the Soul

Jim Elvidge - The Singularity Will Not Occur, Programmed Reality & Infomania

William Henry - Stargate Technology & Transhumanism

Aaron Franz - TransAlchemy, Save the Humans!

Aaron Franz - The Age of Transitions

Michael Tsarion - The Post Human World