How do we stop UK publishing being so posh and white?

Nikesh Shukla, writer

Latest work: Meatspace (Friday Project)

I’m writing this hoping it’ll be my last piece on diversity in publishing. I am tired. Tired of fighting for representation for writers of colour, pushing for more black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) people to be in positions of management in the industry. I am tired of sitting on panels about diversity, writing pieces about diversity, and tweeting about prizes, review coverage and lists that ignore diversity. Which is why I lost my patience at the end of November when the titles announced for the 2016 World Book Night – when free books are distributed to encourage reading – failed to include a single BAME author. It might seem heartless to criticise a brilliant charity for wanting to put books in the hands of non-readers, and, in response, World Book Night expressed frustration that no publishers had put forward any BAME writers.

It is important that we all take collective responsibility for increasing inclusion across books. It’s hard speaking out about these things. Writers worry that it will make us look bitter or “difficult”, rendering us unpublishable. This year’s diverse Man Booker shortlist should show that BAME writers are world-beating, but according to the recent Spread the Word’s Writing the Future report BAME writers are worse-off now than they were 10 years ago. It also revealed that there were shockingly few BAME writers appearing at all the literary festivals in the country (and there’s one running pretty much every week).

Bookmarks is our new weekly email from the books team with our pick of the latest news, views and reviews, delivered to your inbox every Thursday

Talking with my friend, the poet and broadcaster Musa Okwonga, I said I’d love to see a collection of essays by BAME writers. I joked that it would increase diversity in publishing by 20%. Musa reminded me of the Chinua Achebe quote: “If you don’t like the story, write your own.” So I did. I spoke to the crowdfunding publisher Unbound about putting together such a collection and they were excited. We gathered an initial list of names, purposefully opting for up-and-coming and emerging voices rather than established ones, and hit the go button. The response was astonishing. We were one-third funded by the end of the first day. And at the end of day two, when we were already quietly confident about being fully funded within the month, something amazing happened: JK Rowling pledged to be a patron, and bumped us up to two-thirds funded. We were fully funded by the middle of the following day. Even without Rowling’s kind patronage, the support showed us that there is a hunger for this book, for these voices.

Then there are the bloggers Naomi Frisby and Dan Lipscombe, who have launched #diversedecember, “a celebration of books by BAME writers”, doing what they do best, campaigning through word of mouth. Publishers such as Nosy Crow and Influx issued a call for BAME authors, and agents are asking me to send any I know of their way.

I’m glad that the noise online has contributed to the industry taking a long, hard look at itself. If we need to be back here again in five or 10 years’ time, hopefully many other BAME authors will feel empowered to speak up and keep pushing for change.

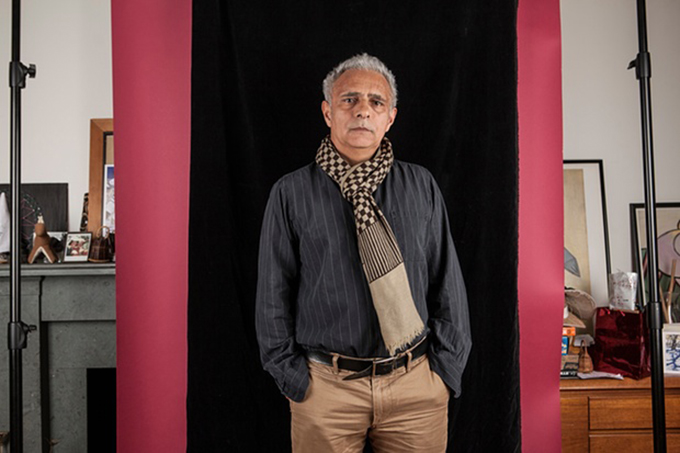

Hanif Kureishi, novelist and screenwriter

Latest work: The Last Word (Faber)

Photograph: Antonio Zazueta Olmos

The publication in the mid-1980s of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, my The Buddha of Suburbia in 1990 and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth in 2000 changed the notion of what a successful book could be. In terms of content, publishers, and obviously audiences, are very happy to read books by and about so-called ethnic minorities. Marlon James winning the Booker this year with A Brief History of Seven Killings proves that remains the case. Readers are always fascinated to hear from new and innovative writers. As with sports, or even entertainment, the problem is not the artists but the structure of the industry. There are many black footballers, but there are far fewer black managers or agents. And it is the same in publishing: the social makeup of the industry (the editors, agents and so on) is almost always narrower than that of the artists. Therefore what the decision-makers think an audience will like is often quite limited. This is also the case, certainly in my experience, in film and TV, where, as a younger man, I was often told: “These are really good, but why can’t you make the characters white?” The industry must change, but it will only do so if it is aware that, to survive, it has to have new voices; that any culture can only be kept alive by the new. Publishers will have to hear people who haven’t spoken before.

Kamila Shamsie, novelist

Latest novel: A God in Every Stone (Bloomsbury)

Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

Words such as “representation” and “diversity” make the whole matter seem so worthy. I prefer to put it this way: there are stories out there we aren’t hearing, stories that could better help us understand the complexity of this nation in which we’re living, stories that could make the worlds of strangers feel intimate. Surely that’s a loss? There’s no point falling for the divide-and-rule tactic that sets writers up against readers (I’m looking at you, Marlon James, for arguing that publishers too often seek fiction that “panders to that archetype of the older white woman”). People who love fiction are those prepared to make imaginative leaps into worlds not their own – some more than others, it is true, given all the studies and anecdotal evidence that tell us that women read more widely than men. It is not readers who need to be reconditioned, but the machinery that gets books on people’s radars and into their hands that needs to be reconditioned: publishers and booksellers are central to that machinery. A vital part of the reconditioning is to make the people in those businesses more “representative” of Britain – not only in terms of ethnicity, but also class. Specifically, a more successful version of the Arts Council’s Decibel programme, which showcases artists and companies with diverse practice, needs to be put in place to recruit employees from a wide range of backgrounds, and not just as a short-term project. The days when you walk into a publishing party and correctly assume that the handful of people who aren’t white are authors rather than publishers need to be quickly consigned to the past. And please don’t call me BAME, an acronym that’s just one Latino away from BLAME.

Margaret Busby

First black female publisher in the UK, co-founder of Allison & Busby

I don’t deny it’s a bore to have to address the same topic for 30 years. Longer, if you count from when, as a new graduate, I applied for a job with a big publisher and was granted an interview – only to turn up and have the doorkeeper call upstairs: “There’s a black girl here who says she has an appointment.” Ah, well. I persevered with co-founding Allison & Busby, while attracting newspaper headlines betraying as much astonishment as Dr Johnson might have expressed at seeing a dog preaching: “The girl from Ghana goes into publishing.”

At one job interview the doorkeeper called upstairs: 'There’s a black girl here who says she has an appointment.'

In the 1980s I helped found Greater Access to Publishing (GAP), a group (including Jessica Huntley of Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications and Lennie Goodings of Virago) that campaigned to diversify the industry. An article Lennie and I wrote for the trade press in 1988 began with a Toni Morrison quote – “It’s not patronage, not affirmative action we’re talking about here, we’re talking about the life of a country’s literature” – and went on to pose such questions as: “What are publishers doing to make their companies more accurate reflections of their lists, readers and society?”

Following GAP, the early 90s brought an Arts Council initiative of publishing traineeships for black and Asian candidates, whom I helped mentor. In 2004, the Bookseller report In Full Colour concluded that publishing was “largely a white, middle-class industry” that made black, Asian and minority-ethnic publishing professionals and writers feel marginalised. Then another Arts Council training scheme was developed to try to address representation in the publishing workforce. The Diversity in Publishing Network, founded in 2005, for several years did its best to make a difference. Then came Equip, with a publishing equalities charter in 2012. But try playing “Spot the brown face” in the 2015 Bookseller list of the 100 most influential people in UK publishing.

Why does the mainstream publishing industry seem content to remain so undiverse? What comes to mind is the reply given by Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Britain’s first black Oscar nominee, on being asked why she hadn’t been getting parts in Britain: “I can’t tell you why I’ve not been invited to a party. You need to go to the host and say, Why didn’t you invite her?”

Danuta Kean

Editor of Writing the Future

Spread the Word’s Writing the Future was the second report I edited in 10 years that looked at diversity among novelists and publishers. Both reports found that everyone from agents to publishers was enthusiastic about diversity. So why is the publishing world still so white? Time and again, agents, publishers, festivals and creative writing courses have been blind to the lack of black and Asian faces. They just don’t notice it until it is pointed out.

Senior managers have to commit to systemic and sustainable change. This isn’t about making the industry feel good. Monocultures are bad for business. Based on a year’s research and in-depth interviews, Writing the Future made the business case for diversity and listed 14 recommendations that will bring change. If the book trade doesn’t change, it will be in trouble: within 20 years the UK BAME population will be 25%. If books don’t reflect that, they will become increasingly irrelevant and unprofitable.

Simon Prosser

Publishing director, Hamish Hamilton

Photograph: Eamonn McCabe for the Guardian

The publishing industry has a real problem with diversity in terms of staffing. I’d like our industry to reflect the diversity I see as I walk down my street. There is a strong ethical reason to want this, but also a business reason: that street is a reflection of our market, and we need editors, designers, publicists and salespeople who reflect it too.

So what is to be done? There are deep socioeconomic and class issues that create barriers to education and job prospects, beginning at pre-school, compounded by the fact that most British publishing companies are located in one of the world’s most expensive cities. But there are practical steps that the industry can take.

The first and simplest step is to provide access – an entry point for more diverse recruitment. The charity Creative Access has worked with a range of publishers and literary agents to provide paid internships for young people from BAME backgrounds. And there are company-specific initiatives too: for the past six years, Hamish Hamilton has hosted the annual Helen Fraser fellowship, providing a paid six-month traineeship to BAME candidates. So far, two have found jobs at major publishing houses, two are working in related fields, one wanted to stay within publishing but had visa issues, and one is sitting at the next desk to me as I type.

As for the issue of representation of BAME authors on publishers’ lists, we need – again – to improve access, and also to find ways to reach people outside what the Writing the Future report terms the “old monoculture”. Luckily, there are partners we can work with. The Caine prize for African writing, the Muslim writers awards and the DSC prize for south Asian literature, for example, do a great job in showcasing diverse writers, as do magazines such as Wasafiri and SABLE LitMag.

Arts Council England has a strong interest in representation too. Hamish Hamilton collaborated for three years with the Decibel initiative, running an annual competition for unpublished BAME writers, judging them and publishing the best in a series of three annual anthologies. The most promising of these found agents for their work and the monoculture became a little more diverse.

There is a long way to go, but it is a challenge to be relished. There is an ethical imperative for publishers to reflect diversity because we are part of a culture industry that speaks for and determines what “culture” is, and that isn’t solely concerned with profit.

Daljit Nagra, poet

Latest work: Ramayana: A Retelling (Faber)

Here are 10 random, patronising considerations for the judges of British literary prizes:

- Taste is subjective and is established by personal factors such as your upbringing.

- If you think you’re liberal-minded and, therefore, fair- and open-minded, you’re probably the most dangerous person for minority writers; you probably think your taste is broadly representative and takes the middle ground.

- Would you ever start any judging meeting by considering whether you’ve circumvented your own taste and liberal paradox (as in 2) with an unembarrassed articulation of all possible constituencies you might seek to address?

- Is at least one of you not a white male?

- Is the (token?) non-white, non-male judge genuinely representative of a different constituency or someone who seems media-friendly rather than passionate about the issue he/she appears to represent?

- Is the judging process also a chance for the panel to learn about their own process as a team and to articulate this, instead of simply saying what a good list this is or what a good year it has been?

- Are nearly all the judges from cosy middle-class backgrounds or are we serious about appealing to a wider audience of readers?

- As an aside. To even enter the game, how many of the major poetry publishing houses would ever dare to publish a black/Asian poet’s first book? Especially given that such poets have been publishing poetry in Britain for more than 50 years. I notice Picador published the wonderful Kate Tempest’s first collection, but would they ever consider publishing other performance poets, particularly from the long tradition of non-white performers?

- hould all publishers be held statistically accountable for their white shame?- Minority writers, such as myself, need a language to help us address our own prejudices.

Sarfraz Manzoor, writer and broadcaster

The world is run by posh white people, so if you want to get on, it helps to know how to deal with, speak and appeal to them. In that sense, publishing is no different from other parts of the media, politics or anything else. I would welcome diversity in publishing, but would be wary of an excessive focus on race and religion – where are the stories of white working-class kids who do not grow up to be journalists, footballers or criminals? With respect to ethnic diversity, publishing possibly fetishes extreme tales – the Asian woman fleeing honour killing, the Muslim man who flirted with extremism – so I would welcome writers from minority backgrounds being given the space to write beyond those confines and to show that one can be brown without being sad, mad or dangerous.

Jackie Kay, writer and poet

Latest collection of short stories: Reality Reality (Macmillan)

In the year of Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, the narrow and undiverse World Book Night list is somewhat staggering. An irony too much surely that World Book Night should morph into something ungenerous and garish: White Book Night. I’m a huge fan of WBN, and found it thrilling when my book Red Dust Road was on the list a few years back. But surely after last year’s concerns about the lack of translations and this year’s monocultured selection, it is time for the process of selection to be reassessed.

It seems as if life is in many ways harder for BAME writers now than it was in the 70s and 80s, as if things that appeared to have moved forward are turning back.

But then Diverse December lifts the Christmas spirits. It would be too sad for us all to end up in some kind of Dickensian hell. Carol Ann Duffy, whose Love Poems is on the shortlist, said: “I’m a huge supporter of WBN and grateful to be included, but more than happy to give up my place to support diversity, which is the lifeblood of all culture.” I’m wondering whether the WBN panel should either make another list – a #diversedecember list – or make some serious decisions on how the books will get chosen next year.

Neil Morrison

Group HR director, UK and international, at Penguin Random House

Publishing is often misunderstood: what it is, what it does and, therefore, the sort of people it attracts. For a variety of reasons, some intentional and others cultural, it has been pretty much a closed system for years. “The Scheme” at Penguin Random House was designed to change external perceptions, but also to challenge internal assumptions about talent and what is “required” to work in publishing. It is a 13-month marketing trainee programme, with a proper salary, training, mentoring and a good chance of a full-time job at the end. What sets it apart is the approach taken to recruit and select the participants.

The Scheme was launched on Tumblr and supported by a diverse social media campaign. There were just two criteria: to have finished full-time education by September 2015, and to have the right to work in the UK. There were no CVs, no application forms, no demographic or personal details – just an email address. We posed seven questions designed around the qualities of modern marketeers. More than 800 candidates answered the questions and 50 went through to pitch a creative marketing campaign for the 150th anniversary of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland via a digital interview-on-demand platform.

Finalists completed four creative challenges designed to assess the seven qualities and mimic the everyday tasks new recruits would carry out. The final four are: a 27-year-old cake-business owner; a Toronto-born history graduate; a sixth-form student; and a former software sales executive. What they have in common is that none of them would have applied through the traditional CV route. We now want to take this further and roll out a similar programme for editorial roles.

Bernardine Evaristo, writer

Latest novel: Mr Loverman (Hamish Hamilton)

In the 1980s and 1990s the Arts Council initiated publishing apprenticeships to increase diversity. In the long term these projects failed and, if anything, the publishing industry is even less diverse than it was 10 years ago when Ellah Allfrey and Elise Dillsworth were commissioning fiction editors at large publishing houses. Unfortunately, the huge success of one or two writers gives the impression that there isn’t a problem. And while the industry finally opened its doors to African fiction a decade ago, black British writers have all but disappeared. I know that, as a literary writer who isn’t a bestseller but who continues to be published, I am a rare exception. The long-term solution is to appoint editors from within the underrepresented communities and to provide the resources for them to find, develop and market the brilliant authors out there who are writing the untold stories.

In 2005 I initiated an Arts Council report that revealed that less than 1% of poetry books in the UK were written by black or Asian poets. In 2007 I initiated the Complete Works mentoring scheme (campus.poetryschool.com), with Nathalie Teitler as director and Carol Ann Duffy as patron. So far, 20 poets have been mentored by Britain’s leading poets, including Sean O’Brien, Michael Schmidt, Pascale Petit, Mimi Khalvati, Daljit Nagra, Patience Agbabi and Paul Farley. The 20 mentored poets, including Warsan Shire, Sarah Howe, Karen McCarthy Woolf, Roger Robinson, Mona Arshi, Malika Booker, Jay Bernard and Inua Ellams, have gone on to win or be nominated for more than 40 awards. They have enriched and changed the face of British poetry. Applications are now open for a new set of 10 poets to be mentored from next year.

Nick Barley

Director, Edinburgh international book festival

Ten attempts to make a difference:

- I will buy another copy of The Fishermen by Chigozie Obioma and give it to someone as a Christmas present.

- I will invite Yewande Omotoso to visit Edinburgh from South Africa to talk about her novels.

- I will passionately recommend César Aira’s peerless novellas in a piece for the Guardian.

- I will pledge to increase the number of people from a variety of ethnicities and backgrounds moderating book festival events in future.

- I will invite Jackie Kay to talk to Syrian refugees in Scotland and share their stories at the book festival.

- I will do whatever it takes to get people to read Raja Shehadeh’s books.

- I will try to persuade Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to visit the UK with a group of emerging African writers.

- I will promise Jacques Testard at Fitzcarraldo that if he publishes any more of the Nocilla novels by Agustín Fernández Mallo, I’ll buy five copies of each.

- I will buy my mother a gift subscription to And Other Stories.

- I will ask Kamila Shamsie and Mohammed Hanif to recommend Pakistani writers not yet known here, and invite them to Edinburgh in memory of the literary events organiser Sabeen Mahmud, who was assassinated in Karachi earlier this year.

Juliet Mabey

Publisher, Oneworld

The lack of diversity in the UK book industry might well be to do with the lack of diversity in both publishing and bookselling staff. However, more needs to be done, and in many cases it is up to editors to spearhead this change. When setting up its fiction list six years ago, Oneworld took this mission very much to heart, intending to publish books by writers from all over the world, primarily for the obvious reason that people from different cultures, races and genders tell stories that are loaded with a richly diverse range of meanings. It is this diversity that enriches our readers. The first novelist I signed up was Marlon James in 2009, and since then we have published British Asian, British African and mixed-race British novelists. Our relatively small fiction list now boasts writers from 32 countries, from India to Somalia, Jamaica to Iceland.

The climate is right for greater diversity in publishing, and the market is ready to be challenged more, but perhaps, in the short term, it requires more affirmative action. Prizes can go a long way to identify and promote excellence in a particular field, as we have seen with the wonderful Baileys women’s prize for fiction, and something like this for BAME authors could be effective. An annual survey of review coverage, and perhaps a dedicated bay in bookshops, could also help. Certainly, more could be done.

Ellah Wakatama Allfrey

Critic, editor and Booker judge 2015

I found it interesting that so many reviews and comments on this year’s Booker prize longlist and shortlist highlighted the “diversity” of the books included. Why should this be something unusual? Surely, if we are seeking excellence – as judges, publishers, readers – the only way to find it is to read widely, fearlessly. To my mind, any list that comes up with the same kinds of writers, the same kinds of stories, just hasn’t tried hard enough. The problem is never the writers. There is creative excellence in abundance, even when we find ourselves limited to the English language, or within our national borders. And the problem is not with the readers, who time and again prove that they buy books for the adventure of new discovery and that they are more than capable of dealing with experiences beyond their own. The problem lies behind the scenes, in the acquisitions meetings, in the makeup of the judging panels, in the composition of the editorial teams and the festival programming committees. If the faces around the table don’t reflect a wide range of experience and reading, it is no surprise that the names on the list will share that deficit.

The problem lies behind the scenes, in the acquisitions meetings, in the makeup of the judging panels

Every five years or so there is this ritual lament about a lack of diversity – a report on the monochrome nature of the industry, dismay at important lists that ignore the output. I am bored with the conversation. It’s simple: you cannot have excellence without diversity. As soon as the gatekeepers and opinion formers agree to take this as a central tenet, both the outrage and self-flagellation can stop and we can all get on with the hugely enjoyable task of helping talented writers find their ready and willing readers.

Andrew Franklin

Founder and publisher, Profile

There is a suspicious lack of diversity in literary fiction and non-fiction, and, perhaps most of all, in commercial fiction. And the same is true in publishing houses, where things are improving but not fast enough. The noise that #diversedecember is making is certainly helping. But here are six things that every publisher should be doing now. First, pay all interns and junior staff a living wage. If people aren’t paid, only those whose mums and dads can help out can work. Second, look hard at conscious and, even more, unconscious bias in recruitment. There are simple steps to take to make sure that unknown prejudices aren’t creeping into the selection process. There are lots of great schemes out there but let me plug much the best operation around: Rare Recruitment, a specialist recruiter who “connects exceptional people from diverse backgrounds with great jobs in top organisations”. In fact, the media should be on to this – publishers are bad, but none of the media shine either. Third, set up a mentoring scheme for BAME staff, interns and applicants. Some BAME junior employees feel abandoned, and one young Pakistani woman told me she was so bullied at one of the big conglomerates that she had to leave. Fourth, call on Creative Access, set up to place outstanding BAME candidates throughout the media. The Tories have pulled the funding for this great scheme, so supporting it is more important than ever. Fifth, help BAME writers on creative writing courses and elsewhere. And sixth, attend to class as much as race. Publishing is monstrously middle-class.

None of this is very difficult or demanding. And if people don’t do it, publishing will never change. We are what we read.

Aminatta Forna, writer

Latest novel: The Hired Man (Bloomsbury)

On the bright side, I expect I would not have been published 40 years ago, so there has been change and there are publishers who are outward-looking and internationally minded. The question is why so much of the industry has remained so parochial. I think it goes back to university and the so-called canon, which has long defined English literature as essentially white. The mindset has filtered through publishing, which is staffed by English literature grads. The teaching of literature at an American university, where I am now, is a thousand times more international. My advice to any struggling author of colour is to look for a publisher overseas; after all, there is nothing as universal as stories. On the other hand, Cassava Republic, the Nigerian-based publishing house, is setting up a UK imprint. I read a delightful novel by a British Nigerian writer whom they’ll be publishing, so if British publishers aren’t interested in local talent, somebody else is.

Isobel Dixon

Director, Blake Friedmann literary agency

As a South African literary agent working in London for the past 20 years, I’m acutely aware of the lack of diversity in both South African and British publishing as far as staffing is concerned, and I feel the anger and frustration. One problem is the tendency to draw on a shallow pool of privilege, exacerbated by the tendency to rely on an inequitable system of unpaid internship programmes (outside of approved student internships required by courses). Selection in a silo. At BFA we offer a three-month paid contract for entry-level assistants.

As for content, other European countries such as France, Holland and Sweden can be more adventurous. My Asian and African clients often receive a swifter and warmer welcome on the continent. In the UK there is a leaning towards the “foreign-known”, the “exotic-lite” – something a little bit unusual but not too different, a narrow view of immigrant lit. A writer such as Zakes Mda, hugely acclaimed in South Africa and America, is currently unpublished in the UK for his latest work Little Suns, which offers a fresh perspective on a key event in South African/Xhosa history. He is a writer who doesn’t fit into any easy categorisations – and, yet, isn’t diversity of style, narrative and subject matter part of what all of us in publishing should be looking for, beyond familiar horizons?

Stephen Page

Chief executive, Faber and Faber

Like many publishers, we’ve made steps to encourage greater diversity both in the company and the industry, especially around our internships and partnership with Creative Access. At present, as in much of the creative sector, that has yet to lead to much movement towards a representative demography. Progress might be made using the government’s drive towards apprenticeships. While this initiative needs to be adapted to be suitable for the creative sector, it can be turned to good use to encourage routes into the industry in support of greater diversity.

Akhil Sharma, novelist

Latest novel: Family Life (Faber)

I have benefited from being an ethnic writer. All fiction writers want their stories and novels to feel like something new. Because I am writing about things that are not well known, and I am writing about a community that people are curious about, I have received a great deal of attention. I am not saying that my writing is not meritorious. I am only saying that my complaining would feel churlish since I have benefited so much from being a minority.

All that aside, I have had the feeling that books by whites are considered more universal, more the general case. I am quite hopeful about the future, though. As society changes, so do readers and editors.

Source: theguardian.comComments