The CIA’s Most Highly-Trained Spies Weren’t Even Human

Source: smithsonianmag.com

As a former trainer reveals, the U.S. government deployed nonhuman operatives—ravens, pigeons, even cats—to spy on cold war adversaries

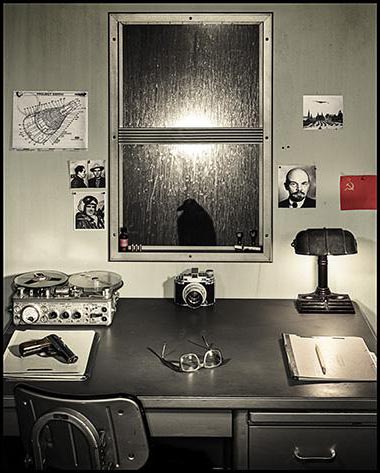

There would be a rustle of oily black feathers as a raven settled on the window ledge of a once-grand apartment building in some Eastern European capital. The bird would pace across the ledge a few times but quickly depart. In an apartment on the other side of the window, no one would shift his attention from the briefing papers or the chilled vodka set out on a table. Nor would anything seem amiss in the jagged piece of gray slate resting on the ledge, seemingly jetsam from the roof of an old and unloved building. Those in the apartment might be dismayed to learn, however, that the slate had come not from the roof but from a technical laboratory at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. In a small cavity at the slate’s center was an electronic transmitter powerful enough to pick up their conversation. The raven that transported it to the ledge was no random city bird, but a U.S.-trained intelligence asset.

Half a world away from the murk of the cold war, it would be a typical day at the I.Q. Zoo, one of the touristic palaces that dotted the streets of Hot Springs, Arkansas, in the 1960s. With their vacationing parents inca tow, children would squeal as they watched chickens play baseball, macaws ride bicycles, ducks drumming and pigs pawing at pianos. You would find much the same in any number of mom-and-pop theme parks or on television variety shows of the era. But chances are that if an animal had been trained to do something whimsically human, the animal—or the technique—came from Hot Springs.

Two scenes, seemingly disjointed: the John le Carré shadows against the bright midway lights of county-fair Americana. But wars make strange bedfellows, and in one of the most curious, if little-known, stories of the cold war, the people involved in making poultry dance or getting cows to play bingo were also involved in training animals, under government contract, for defense and intelligence work. The same methods that lay behind Priscilla the Fastidious Pig or the Educated Hen informed projects such as training ravens to deposit and retrieve objects, pigeons to warn of enemy ambushes, or even cats to eavesdrop on human conversations. At the center of this Venn diagram were two acolytes of the psychologist B.F. Skinner, plus Bob Bailey, the first director of training for the Navy’s pioneering dolphin program. The use of animals in military intelligence dates back to ancient Greece, but the work that this trio undertook in the 1960s promised an entirely new level of sophistication, as if James Bond’s Q had met Marlin Perkins.

“We never found an animal we could not train,” says Bailey, 76, who in his career has done everything from teaching dolphins to detect submarines to inventing the Bird Brain, an apparatus that enabled a person to play tick-tack-toe against a chicken. (One is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.) “Never,” he repeats, as we sit in the book-cluttered living room of his modest lakefront house in Hot Springs. “Never.”

As I try to summon particularly challenging creatures—Alligators? Moles? Crustaceans?—he asks, “Do you know who Susan Garrett is?” I do not. Garrett, it turns out, is a world champion trainer in the sport of dog agility. A few years ago, Bailey was teaching a course on stimulus control for her students. His stimulus was a laser pointer. One day, he was in the bathroom and saw a spider. “I looked down at this spider and said, hmmm.” He took out his laser, turned it on, and gently blew on the spider. “Spiders don’t like wind—it blows their web down,” he says. “They pull themselves down into the smallest size they can get and hunker down.”

Turn on laser. Blow. Turn on laser. Blow. Bailey did this at several intervals during the day. “By the time I finished all I had to do is turn that light on,” he says, and the spider would go defensive. He returned to the classroom where Garrett was lecturing and announced: “You’ve got a trained spider in your bathroom.”

[...]

Read the full article at: smithsonianmag.com