An Ancient History of War and Trade, Plunder and Peace

The following articles demonstrate that just when archaeologists and anthropologists think they’ve got it sorted out, new information flips everything around. The more we learn about history the more we realize it’s a work in progress, and our (generally incorrect) assumptions about ancient societies come directly from our modern understanding and point of view.More on peace-niks and warriors in history...

---

Pre-Incan Culture Didn’t Rule by Pillage, Plunder and Conquest

By April Holloway | Ancient Origins

New research published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology has suggested that the Wari, an ancestor culture to the Incas, were able to flourish expand their territory through trade and semi-autonomous colonies rather than through conquest.

The Wari civilization flourished from about 600-1000 AD in the Andean highlands and forged a complex society widely regarded today as ancient Peru’s first empire. Their Andean capital, Huari, became one of the world’s great cities. Relatively little is known about the Wari because no written record remains, although thousands of archaeological sites reveal much about their lives. Until now it was believed the Wari established a strong centralised control – economic, political, cultural and military – like their Inca successors to govern the majority of the populations living across the central Andes. However, the latest research draws this theory into question.

The researchers examined the settlement patterns of the pre-Columbian culture using archaeological surveys and geographic mapping and found that rather than radiating out in a continuous circle from Pikillacta, a huge city with massive investment, the Wari area of rule was patchier. They started out by creating loosely administered colonies to expand trade, provide land for settlers and tap natural resources across the central Andes.

[...]

Read the full article at: ancient-origins.net

---

’Peaceful’ Minoans Surprisingly Warlike

By Stephanie Pappas | LiveScience

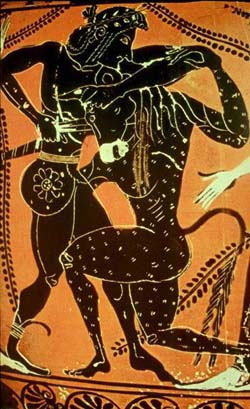

The civilization made famous by the myth of the Minotaur was as warlike as their bull-headed mascot, new research suggests.

The ancient people of Crete, also known as Minoan, were once thought to be a bunch of peaceniks. That view has become more complex in recent years, but now University of Sheffield archaeologist Barry Molloy says that war wasn’t just a part of Minoan society — it was a defining part.

The ancient people of Crete, also known as Minoan, were once thought to be a bunch of peaceniks. That view has become more complex in recent years, but now University of Sheffield archaeologist Barry Molloy says that war wasn’t just a part of Minoan society — it was a defining part."Ideologies of war are shown to have permeated religion, art, industry, politics and trade, and the social practices surrounding martial traditions were demonstrably a structural part of how this society evolved and how they saw themselves," Molloy said in a statement.

The ancient Minoans

Crete is the largest Greek isle and the site of thousands of years of civilization, including the Minoans, who dominated during the Bronze Age, between about 2700 B.C. and 1420 B.C. They may have met their downfall with a powerful explosion of the Thera volcano, which based on geological evidence seems to have occurred around this time.

The Minoans are perhaps most famous for the myth of the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull that lived in the center of a labyrinth on the island.

Minoan artifacts were first excavated more than a century ago, Molloy said, and archaeologists painted a picture of a peaceful civilization where war played little to no role. Molloy doubted these tales; Crete was home to a complex society that traded with major powers such as Egypt, he said. It seemed unlikely they could reach such heights entirely cooperatively, he added.

"As I looked for evidence for violence, warriors or war, it quickly became obvious that it could be found in a surprisingly wide range of places," Molloy said.

War or peace?

For example, weapons such as daggers and swords show up in Minoan sanctuaries, graves and residences, Molloy reported in November in The Annual of the British School at Athens. Combat sports were popular for men, including boxing, hunting, archery and bull-leaping, which is exactly what it sounds like.

Hunting scenes often featured shields and helmets, Molloy found, garb more suited to a warrior’s identity than to a hunter’s. Preserved seals and stone vessels show daggers, spears and swordsmen. Images of double-headed axes and boar’s tusk helmets are also common in Cretian art, Molloy reported.

Even the yet-undeciphered language of Minoan may hint at a violent undercurrent. The hieroglyphs include bows, arrows, spears and daggers, Molloy wrote. As the script is untranslated, these hieroglyphs may not represent literal spears, daggers and weapons, he said, but their existence reveals that weaponry was key to Minoan civilization.

[...]

Read the full article at: livescience.com

READ: Is it natural for humans to make war? New study of tribal societies reveals conflict is an alien concept

Tune into Red Ice Radio:

Roundtable - Man’s Genesis & The Future Direction of Humanity

Steven & Evan Strong - Aboriginal Origins & Egyptian Glyphs in Australia

John Anthony West - Ancient Egypt

Joseph Atwill & Ryan Gilmore - Religious Mind Control, Ancient Warfare & Modern Conflicts

Robert Bauval - Black Genesis, The Ancient People of Nabta Playa & Mars Anomalies

Robert Schoch - The Mystery of the Sphinx, Forgotten Civilization & Catastrophic Solar Outbursts

John Anthony West & Laird Scranton - Göbekli Tepe, Egypt & The Dogon