Antibiotics Can’t Keep Up With ’Nightmare’ Superbugs

Source: npr.org

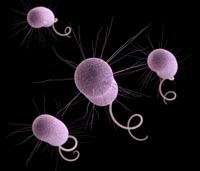

We’re used to relying on antibiotics to cure bacterial infections. But there are now strains of bacteria that are resistant to even the strongest antibiotics, and are causing deadly infections. According to the CDC, "more than 2 million people in the United States every year get infected with a resistant bacteria, and about 23,000 people die from it," journalist David Hoffman tells Fresh Air’s Terry Gross. Many people are familiar with the type of resistant infections often acquired in hospitals, caused by MRSA, the acronym for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. But most people don’t know about the entirely different group of resistant bacteria that Hoffman reports on in Hunting the Nightmare Bacteria, airing Tuesday on PBS’ Frontline. The show explores an outbreak of resistant bacteria at one of the most prestigious hospitals in the U.S., and explains why there is surprisingly little research being conducted into new antibiotics to combat these new superbugs.

Many people are familiar with the type of resistant infections often acquired in hospitals, caused by MRSA, the acronym for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. But most people don’t know about the entirely different group of resistant bacteria that Hoffman reports on in Hunting the Nightmare Bacteria, airing Tuesday on PBS’ Frontline. The show explores an outbreak of resistant bacteria at one of the most prestigious hospitals in the U.S., and explains why there is surprisingly little research being conducted into new antibiotics to combat these new superbugs."We really have a big information black hole about these really, really dangerous bacteria, and we need to know more, and it ought to be a national priority," Hoffman says.

On how bacteria have evolved to be resistant to our antibiotics

Bacteria have been training at this for a long, long time. I think when a lot of people took antibiotics in the ’50s and ’60s, there was a lot of talk then about "miracle drugs" and "wonder drugs" ... Had we basically pushed back those evolutionary forces? Had we essentially found a way to avoid infectious disease? Well, what we’re seeing is this evolutionary process in bacteria. It’s relentless, and what happened here was [that] bacteria learned to basically teach each other to swap these enzymes and help each other learn how to beat back our best antibiotics; our last-resort antibiotics didn’t work. ...

In the period before World War II ... people that got infections, they had to cut it out. They had to cut off limbs, cut off toes, because there weren’t antibiotics. And oftentimes, when people talk about the fact that we might have to go back to a pre-antibiotic age, that’s what they mean — that a simple scrape on the playground could be fatal.

On how pharmaceutical companies don’t have economic incentive to develop new antibiotics

[In the ’50s and ’60s] I think there was something like 150 classes of new antibiotics. And although there were warnings then that if we misused them that resistance would grow, you could just see in the marketplace new ones coming on every couple of years. ... I think we got very, very complacent. ... In the ’80s and particularly in the ’90s we went around the bend a little bit because the science didn’t continue to produce new antibiotics at that rate, and the economics of drug development changed rather remarkably. ...

We’re bombarded with advertisements that there are drugs now to treat chronic diseases ... that you would take for the rest of your life. And you can imagine, if you’re in drug development, if you create and invent one of these drugs that can tackle a chronic disease that people will take forever, the return on investment for the drug companies to develop those big blockbuster drugs ... that became irresistible.

[...]

Read the full article at: npr.org

READ: Report links antibiotics at farms to human deaths