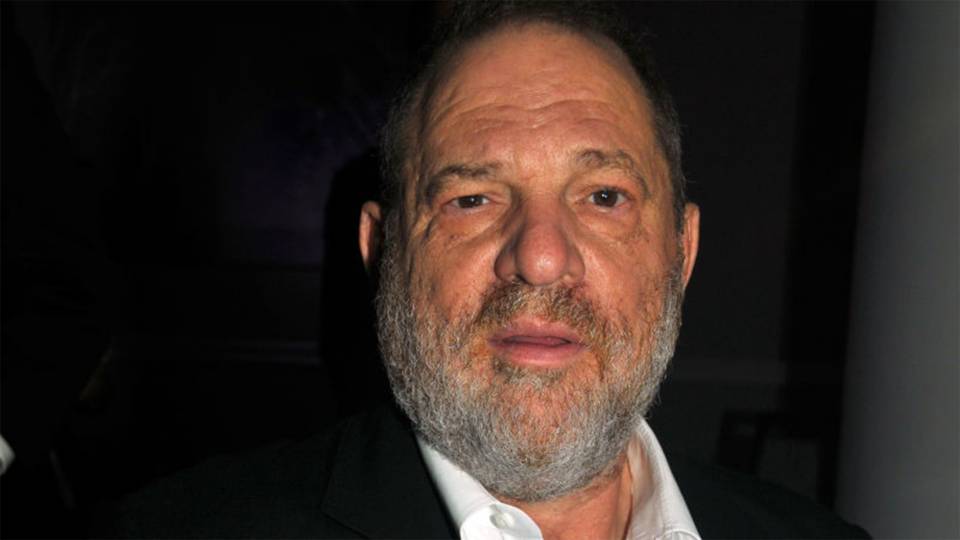

Decades of Sexual Harassment Accusations Against Harvey Weinstein

Two decades ago, the Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein invited Ashley Judd to the Peninsula Beverly Hills hotel for what the young actress expected to be a business breakfast meeting. Instead, he had her sent up to his room, where he appeared in a bathrobe and asked if he could give her a massage or she could watch him shower, she recalled in an interview.

“How do I get out of the room as fast as possible without alienating Harvey Weinstein?” Ms. Judd said she remembers thinking.

In 2014, Mr. Weinstein invited Emily Nestor, who had worked just one day as a temporary employee, to the same hotel and made another offer: If she accepted his sexual advances, he would boost her career, according to accounts she provided to colleagues who sent them to Weinstein Company executives. The following year, once again at the Peninsula, a female assistant said Mr. Weinstein badgered her into giving him a massage while he was naked, leaving her “crying and very distraught,” wrote a colleague, Lauren O’Connor, in a searing memo asserting sexual harassment and other misconduct by their boss.

“There is a toxic environment for women at this company,” Ms. O’Connor said in the letter, addressed to several executives at the company run by Mr. Weinstein.

An investigation found previously undisclosed allegations against Mr. Weinstein stretching over nearly three decades, documented through interviews with current and former employees and film industry workers, as well as legal records, emails and internal documents from the businesses he has run, Miramax and the Weinstein Company.

During that time, after being confronted with allegations including sexual harassment and unwanted physical contact, Mr. Weinstein has reached at least eight settlements with women, according to two company officials speaking on the condition of anonymity. Among the recipients, The Times found, were a young assistant in New York in 1990, an actress in 1997, an assistant in London in 1998, an Italian model in 2015 and Ms. O’Connor shortly after, according to records and those familiar with the agreements.

In a statement to The Times on Thursday afternoon, Mr. Weinstein said: “I appreciate the way I’ve behaved with colleagues in the past has caused a lot of pain, and I sincerely apologize for it. Though I’m trying to do better, I know I have a long way to go.”

He added that he was working with therapists and planning to take a leave of absence to “deal with this issue head on.”

Lisa Bloom, a lawyer advising Mr. Weinstein, said in a statement that “he denies many of the accusations as patently false.” In comments to The Times earlier this week, Mr. Weinstein said that many claims in Ms. O’Connor’s memo were “off base” and that they had parted on good terms.

He and his representatives declined to comment on any of the settlements, including providing information about who paid them. But Mr. Weinstein said that in addressing employee concerns about workplace issues, “my motto is to keep the peace.”

Ms. Bloom, who has been advising Mr. Weinstein over the last year on gender and power dynamics, called him “an old dinosaur learning new ways.” She said she had “explained to him that due to the power difference between a major studio head like him and most others in the industry, whatever his motives, some of his words and behaviors can be perceived as inappropriate, even intimidating.”

Though Ms. O’Connor had been writing only about a two-year period, her memo echoed other women’s complaints. Mr. Weinstein required her to have casting discussions with aspiring actresses after they had private appointments in his hotel room, she said, her description matching those of other former employees. She suspected that she and other female Weinstein employees, she wrote, were being used to facilitate liaisons with “vulnerable women who hope he will get them work.”

The allegations piled up even as Mr. Weinstein helped define popular culture. He has collected six best-picture Oscars and turned out a number of touchstones, from the films “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” “Pulp Fiction” and “Good Will Hunting” to the television show “Project Runway.” In public, he presents himself as a liberal lion, a champion of women and a winner of not just artistic but humanitarian awards.

In 2015, the year Ms. O’Connor wrote her memo, his company distributed “The Hunting Ground,” a documentary about campus sexual assault. A longtime Democratic donor, he hosted a fund-raiser for Hillary Clinton in his Manhattan home last year. He employed Malia Obama, the oldest daughter of former President Barack Obama, as an intern this year, and recently helped endow a faculty chair at Rutgers University in Gloria Steinem’s name. During the Sundance Film Festival in January, when Park City, Utah, held its version of nationwide women’s marches, Mr. Weinstein joined the parade.

“From the outside, it seemed golden — the Oscars, the success, the remarkable cultural impact,” said Mark Gill, former president of Miramax Los Angeles when the company was owned by Disney. “But behind the scenes, it was a mess, and this was the biggest mess of all,” he added, referring to Mr. Weinstein’s treatment of women.

Dozens of Mr. Weinstein’s former and current employees, from assistants to top executives, said they knew of inappropriate conduct while they worked for him. Only a handful said they ever confronted him.