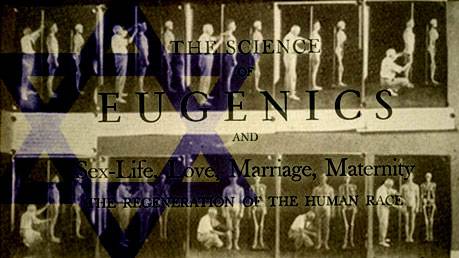

Eugenics in Israel: Did Jews try to improve the human race too?

Source: haaretz.com

In 1944, psychiatrist Kurt Levinstein gave a lecture at a Tel Aviv conference, where he advocated preventing people with various mental and neurological disorders - such as alcoholism, manic depression and epilepsy - from bringing children into the world.

The means he proposed - prohibition of marriage, contraception, abortion and sterilization - were acceptable in Europe and the United States in the first decades of the 20th century, within the framework of eugenics: the science aimed at improving the human race.

In the 1930s, the Nazis used these same methods in the early stages of their plan to strengthen the Aryan race. Levinstein was aware, of course, of the dubious political connotations implicit in his recommendations, but believed the solid and salutary principles of eugenics could be isolated from their use by the Nazis.

Recent research by historian Rakefet Zalashik on the history of psychiatry in Palestine during the Mandate period and following the founding of the state shows that Levinstein was far from a lone voice. Indeed, she claims in her 2008 book, "Ad Nefesh: Refugees, Immigrants, Newcomers and the Israeli Psychiatric Establishment" (Hakibbutz Hameuchad; in Hebrew), that the eugenics-based concept of "social engineering" was part of the psychiatric mainstream here from the 1930s through the 1950s.

Jewish psychiatrists in Israel were not the only ones who tried to distinguish between the science of eugenics, which they held to be useful, and the Nazis' application of it. What set the local experts apart was that they actually studied the foundations of the theory in Germany before immigrating to Palestine, directly from the scientists who supported using eugenics to forcibly sterilize mentally ill and physically disabled Germans - and subsequently to justify their murder. Within a few years, the German scientists were using the same justification for killing Jews.

Many of the Jewish psychiatrists subscribed to their German colleagues' conception of the Jews as a race, relying on the theory that was developed in Europe, says Zalashik. However, upon their arrival in Palestine, they encountered Jews of different types and began to distinguish between the race of European Jews, and that of the Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews (of Middle Eastern and North African origin).

Thus, for example, psychiatrist Avraham Rabinovich, who worked in the Ezrat Nashim facility in Jerusalem and later managed a mental institution in Bnei Brak, drew a distinction in his patient reports from 1921-1928 between the general population, and Jews of Bukharan, Georgian and Persian descent, whom he referred to as "primitive races."

In explaining why the latter were less affected by mental illness, he wrote: "Their consciousness, with its meager content, does not place any special demands on life, and it slavishly submits to the outward conditions, and for this reason, does not enter into confrontation and so gives rise to a relatively very small percentage of functional illnesses in the nervous system and in terms of mental illness in particular."

The views of these psychiatrists meshed with the goals of the Zionist movement, which at the time propounded a policy of selective immigration.

"Eugenics was a part of the national philosophy of most of [the local] psychiatrists," says Zalashik. "The theory was that a healthy nation was needed in order to fulfill the Zionist vision in Israel. There was a powerful economic aspect to this view of things - the idea being to prevent people who were perceived as a burden on society from bringing children into the world. And homosexuals and frigid women also fell into this category."

Psychiatrist Kochinsky, for one, argued in 1938 in the journal Harefuah that the findings of a census of the mentally ill in Palestine should serve primarily as "a basis for methods to improve the race."

Zalashik maintains that such outlooks, as well as other false and harmful assumptions upon which Israeli psychiatry was based in its early years, led to the adoption of inappropriate and sometimes cruel forms of treatment, whose effects on the mental health system in the country are still being felt today.

In her new book, Zalashik chronicles the history of the psychiatric community, which began to take shape in the 1930s with the arrival of dozens of Jewish psychiatrists from German-speaking countries following the Nazis' rise to power. According to her research, at the end of 1933, there were only three psychiatrists working in this country; by the end of World War II, that number had grown to 70. These psychiatrists were influenced by the hypotheses and findings of extensive research conducted in the countries of their birth regarding mental disorders unique to Jews, which was part of the Germans' attempt to explain "the Jewish problem" in biological and medical terms.

"Both Jewish and non-Jewish doctors were wont to think that Jews had a greater tendency to develop mental illness than others," says Zalashik. "The debate was about whether this was because of race, or environmental factors: The Jews said that Jews suffer from mental illnesses because they endured hardship and pogroms, and live in cities where there is more stress and tension than in rural areas. The non-Jews reached the same conclusion, but based it on the argument that Jews were different biologically and genetically."

Zalashik contends that the question of whether the basic premise is accurate is irrelevant to historians. "What's relevant is that the Jewish minority, particularly in Germany, went from being considered a social problem to a medical problem."

Upon immigrating to Israel, the Jewish psychiatrists did not give up the theories in which they had been educated; instead, they adapted them to the newfound situation.

Zalashik: "If, in Europe, the tendency to develop mental illness was said to attest to the Jews' inferiority, then in Palestine it showed the superiority of the pioneers over the Jews from the Old Yishuv [pre-state community]: The psychiatrists said the pioneers came from civilization, and that civilized people suffer from more mental illness than people of the Old Yishuv who lived in a rural environment."

The psychiatrists further maintained that the pioneers tended to develop mental illnesses due to the stress involved in migration and also because of their young age (20-30), known to be a prime period for mental disorders.

One of the main solutions proposed by the psychiatrists was social engineering of the Jewish public in Israel or, as they called it, "mental hygiene." Up until his immigration to Israel in the 1930s, Martin Pappenheim, who ran the neurological department of the city hospital in Vienna from 1921-1923, represented the Austrian branch of the International League for Mental Hygiene - a movement founded in 1908 with the aim of reducing poverty, crime and morbidity by means of drastic preventive measures. In 1935, Pappenheim, together with Dr. Mordechai Brachiahu, founded the association's branch in Palestine.

One of the main arguments in favor of eugenics was the economic benefit it would bring. According to Pappenheim, his association's activity was intended to reduce "the unproductive costs of maintaining the unskilled ... which burden the nation's budget," and to redirect resources to preserving the health of the working population.

Unwanted pregnancies

The recommendations of Pappenheim and his colleagues were partially implemented in the 1930s. In Tel Aviv and Jaffa, "advice stations" for Jews were set up to provide guidance to couples before and after marriage, so as to prevent unwanted pregnancies by those carrying "unhealthy" genetic baggage.

In 1942, Kochinsky gave a lecture on "population policy and psychopathology" at the second conference of the Neuro-Psychiatric Society. He told his audience that of the 200 people he'd treated at the Beit Strauss hygiene center in Tel Aviv, 48 percent had "mental illnesses" with a genetic component, and that these carriers ought not to bear children. These disorders included a whole spectrum of problems, ranging from suicidal tendencies to frigidity and sexual dysfunction. In wake of these "worrisome findings," Kochinsky proposed that a nationwide census be conducted to chart the likelihood of the country's inhabitants to develop mental illnesses, so that measures could be taken to fortify the Jewish race.

Psychiatrists were not the only ones tempted by the allure of eugenics; other doctors in the country, including senior health officials, also tried to adopt its methods. Among the most prominent of these figures during the Mandate was Dr. Yosef Meir, who served for 30 years as chairman of the Clalit health maintenance organization (Kfar Sava's Meir Hospital is named for him). In 1934, in a front-page article in "Ha'em Vehayeled" ("Mother and Child"), a guide for parents put out by the HMO, Dr. Meir wrote the following:

"Who is entitled to bear children? The search for a correct answer to this question is the concern of eugenics, the science of improving the human race and protecting it from degeneration. This science is still young, but its positive results are already of major importance ... Is it not our duty to ensure that our nation shall have sons who are healthy and whole in body and mind?" And he went on to write: "For us, eugenics - in general, and in particular for the sake of guarding against the transmission of hereditary illnesses - has even greater value than it does for other nations! ... Doctors, aficionados of sport, and those active on the national scene must spread the idea: Do not have children if you are not certain that they will be healthy in body and mind!"

"There's a difference between a regular clinic and a eugenic clinic of the kind that were established here," Zalashik notes. "When you come to a regular clinic, the objective is to heal you or to provide some kind of means to ease your suffering. When you come to a eugenic clinic, there are other considerations at work: The caregiver is seeking to heal the Jewish people, to create people with the physical and emotional stamina to fulfill the national vision. Because prevention is a very important element, when a handicapped child was born, for example, they would try to convince the parents not to conceive again."

Aside from such counseling for married couples, support was also provided for sterilization procedures for the mentally ill. Zalashik found a letter from Yehuda Nadibi, the Tel Aviv municipal secretary, to the chief medical officer of the Mandate government, asking him to have a mentally ill woman committed to the psychiatric hospital in Bethlehem - or else he would instruct that she be sterilized. The woman was hospitalized, but then left on a furlough and became pregnant. The social services department in the municipality complained about the financial expense that would be caused by the pregnancy, and asked why the hospital hadn't sterilized her.

Selection committees

The German-Jewish psychiatrists were not unaware of the similarity between their recommendations and the Nazi policy that was implemented at the very same time. Kurt Levinstein even concluded a 1944 lecture with a quote from the German psychiatrist and geneticist Hans Luxenburger, who was involved in legislating eugenic methods in the Third Reich and sought to find scientific proof for the hereditary component of mental illness, in order to promote the government's sterilization initiatives.

"A person in whom hereditary mental illness has not been prevented or cured," quoted Levinstein, "presents just as great a danger to the race as a regular patient, at the height of his suffering ... Eugenic prophylaxis is the only prophylaxis and the ideal prophylaxis for hereditary illnesses."

Levinstein stressed that Luxenburger said these things before the Nazis came to power and, like his fellow Jewish psychiatrists, he sought to differentiate between the Nazi usage and the Zionist usage of eugenic theories. "[The Jewish psychiatrists] argued that it was good science of which the Nazis made evil use in creating a hierarchy of races and annihilating entire peoples," says Zalashik. "They thought of it as an important and effective means of fortifying the nation's health."

The attempts to strengthen the Jewish race by means of controlling births continued after the founding of the state and into the 1950s. In August 1952, a decision was passed by the World Congress of Jewish Physicians to establish a scientific institute dedicated to issues of eugenics in Israel. The institute was never established; eugenic theories were beginning to be abandoned by then, once their basic premises had been proven false and perhaps also as a result of the increased growth and diversity of the psychiatric establishment.

Local Zionist institutions also sought to exert control over the Jewish public's health by means of limitations on immigration. From 1918-1919, offices were opened in various countries, and screened those seeking to move to Palestine. In 1921, an immigration department was founded with the purpose of handling candidates for immigration until their arrival in this country. In the mid-1920s, medical selection committees were established in the immigration offices; in addition, examinations were conducted at the country's ports and in the quarantine facilities run by the Mandatory health authorities.

This selection continued after the Nazis came to power. In late November 1933, Henrietta Szold, then chairwoman of the Youth Aliya department of the Jewish Agency, wrote to Dr. George Landauer, director of the Agency's German division, asking him to oversee the medical examinations of immigration candidates at the Berlin office - since some Jews who'd received certificates had subsequently ended up dependent on Palestine's welfare services due to health problems. Reports about several such cases were circulated among the three organizations involved in emigration from Germany: the Jewish National Committee, the United Committee for the Settlement of German Jews in Palestine (founded in 1932) and the German section of the Jewish Agency.

Selective immigration was officially halted with the enactment of the Law of Return in 1950, which recognized the right of every Jew to immigrate to Israel. But Zalashik asserts that traces of the eugenic viewpoint are still to be found within the Israeli medical system.

"Israel is a superpower in terms of pre-pregnancy tests and abortions," she says. "Abortions are performed here on the slightest pretext, including [correctable] aesthetic flaws such as a cleft palate. The notion that there are some babies that shouldn't be born is part of the eugenic philosophy."

Eugenics wasn't the only dubious theory the German-Jewish psychiatrists brought with them, Zalashik adds: They also adopted German psychiatry's conception of trauma and its method of treating victims of emotional shock.

Many psychiatrists in the young state believed that the psyche of Jews was more resilient due to the persecution they endured throughout history. In 1957, Fishel Shneorson published an article in the journal Niv Harofeh, about the emotional fortitude of Holocaust survivors. He argued that there was a lower rate of mental illness among survivors who immigrated to Palestine/Israel than among those who settled elsewhere.

The theory, widely accepted by psychiatrists here at the time, was that the conditions in this country - the absence of anti-Semitism, combined with the survivors' participation in fighting for and building the nation - had a salutary effect on their mental health. Because of this, psychiatrists tended to attribute a large portion of Holocaust survivors' complaints to immigration difficulties and inter-familial issues, rather than to diagnose them as emotional problems and treat them accordingly.

The dismissive attitude toward the effect of the Holocaust experience is evident in the case of one Romanian-born Jew, who was admitted in 1955 to Jerusalem's Talbieh Psychiatric Hospital to see whether he was suffering from a psychiatric problem. He was described as "possessing borderline intelligence, very weak social understanding and an infantile personality," and diagnosed as suffering from depression, anxiety, insecurity and aggression.

Zalashik: "The therapists devoted three whole pages to the patient's life history, from his childhood up to his hospitalization, but this was all they had to say about his wartime experience: 'In 1941, during the war, the patient was taken to the labor camps and was separated from his family. In the camps he did not suffer from any illnesses. After his release from the concentration camps in 1945, he returned to Romania and learned that his entire family had been wiped out.'"

'Compensation neurosis'

The psychiatrists' attitude toward the survivors' trauma took on added significance in 1952, with the signing of the reparations agreement between Germany and Israel. According to the law in Germany, survivors were entitled to seek compensation for damages caused them by the Nazi persecution. Israeli psychiatrists were asked to write professional opinions about the demands for compensation. Survivors who were not former citizens of Germany, or were not part of the German cultural milieu, were entitled to seek a disability pension from the Israeli Finance Ministry and from the National Insurance Institute, and medical opinions were required for this as well.

Zalashik concludes that instead of using this opportunity to take a closer look at the survivors' psyches and recognize their mental anguish, the psychiatrists primarily saw themselves as the guardians of the state coffers, and were disinclined to acknowledge the psychological harm wrought by the Nazis. And when they did recognize it, they tended to assign the person in question a minimal level of disability.

Psychiatrist Kurt Blumenthal went so far as to claim that many survivors were just pretending to have mental problems, when he wrote in 1953 about "compensation neurosis" or "purposeful neurosis," which was ostensibly characterized by an attempt to portray oneself as having suffered great damage in order to increase compensation one would receive. Psychiatrist Julius Baumetz, director of a Jerusalem mental health station, implored his colleagues to do their utmost to put an immediate end to such allegedly neurosis-driven demands, lest survivors' conditions deteriorate to a state of "infantile dependence."

"The Israeli psychiatrists betrayed their role when they decided to worry more about the state coffers than about their patients," says Zalashik. "When people came to them complaining about nightmares, they told them they were making it up. One German psychiatrist I interviewed said that he was horrified by the opinions he received from Israeli therapists. He said they were so outdated and non-specific that they were harmful to the patients. The theories upon which they were based - i.e., that trauma does not cause any long-term change in personality - were already considered outmoded in Germany in those years."

Zalashik says this atmosphere made it easier for the Health Ministry to decide that mentally ill Holocaust survivors should be treated in private psychiatric institutions instead of by the public health care system. Survivors were kept in these institutions for decades. Eventually, these facilities became hostels; to this day, they are home to about 700 Holocaust survivors.

Another reason this approach in treatment was adopted concerns the status of the psychiatrists themselves, Zalashik believes: "The ones who came from Germany had very different outlooks than that of the Eastern European Zionist establishment that controlled the health system. Many of them had not done a residency, and the medical establishment was not keen to absorb them. Instead of integrating them into the public psychiatric institutions, they let them open private institutions. Once the government discovered that keeping a patient in these institutions was cheaper than keeping him in the public health institutions, it encouraged their proliferation and treatment of the mentally disabled in those frameworks."

Dr. Motti Mark, who headed the Health Ministry's department of mental health services from 1991-1996 and from 1999-2001, worked to close down the private institutions and to transfer their occupants to appropriate government institutions, hostels or community treatment facilities. He becomes visibly emotional when relating how appalled he was when he first encountered them: "[The authorities] created a separate health system for mental patients. I discovered that there were places that they called hospitals, which were actually just like shelters you would find in the United States. These places sprang up outside the big cities wherever there was an abandoned barracks or prison, and they put the patients with the most severe distress there.

"In every abandoned location, the Health Ministry found external solutions, which were supposed to be like complete hospitals, but with an auxiliary doctor or neurologist, who tried to provide full treatment to people with a whole range of problems - anxiety, loneliness, post-traumatic depression - but also nutritional and intestinal problems. In 1991, in one such institution, I saw 30 or 40 people lying in one big room in very poor conditions. I didn't know that such things existed in Israel."

Threat of lobotomy

Zalashik, who today lives in New York, earned a bachelor's degree in general history and sociology from Tel Aviv University. As a student, she also ran a club affiliated with the Hadash (socialist) movement in Tel Aviv. After completing a master's degree in German history, she wrote her master's thesis on the father of German psychiatry, Johann Christian Reil, and began researching the history of psychiatry in the United States. She came to research the subject for her current book after an Israeli friend, a psychiatric social worker, told her that nurses in the hospital where he works often threaten patients who annoy them by saying: "If you don't behave nicely, we'll give you a lobotomy."

A lobotomy is a procedure in which a needle is inserted into the brain via the eye socket and the frontal lobes of the brain are destroyed. The method is based on the presumption that these lobes are the emotional centers of the nervous system, and their neutralizing dulls the emotional response that is troubling the mental patient.

Israeli practitioners continued to recommend insulin therapy for many years after its dangerous effects were documented, including some cases of mortality. While the use of insulin therapy was on the decline in most countries by the first half of the 1950s, it did not start to fade in Israel until the 1960s. In May 1952, for example, a doctor from Talbieh hospital praised insulin therapy, calling it "one of the most effective therapies in the spectrum of modern treatments for schizophrenia." In 1970, nine private mental health institutions (nearly one-third of all those in Israel), were still using insulin therapy.

"Apparently, it is possible to experiment with electroshock, which costs less than insulin and can be done at the Ezrat Nashim Hospital in Jerusalem," the woman wrote. "The treatment must last for three months and afterward there are two possibilities: Either we see that the patients are completely cured, or we see there is no remedy for them at all and transfer them to the hospital in Bnei Brak."

Says Zalashik, "In the early stages, when a new therapy is adopted, there is tremendous enthusiasm and euphoria, and reports of a success rate of 90 percent or higher. Later on, the reports become more reserved, and the question is asked whether the therapy was really helping all the patients or only some. In the third stage, someone declares that these therapies are not working, and at the same time a new therapy arises.

"Some of these therapies were completely unjustified to begin with; the theory upon which insulin therapy was based was nonsense. Part of the justification to use them had to do with the status of the psychiatrists themselves within the medical profession: While doctors in other fields were presenting impressive achievements and discoveries, the psychiatrists were stuck with chronically ill patients who did not respond to any treatment.

Essentially, they knew very little about 'their' diseases, and were unable to show proof of success. They felt it was better to do something than to do nothing. Beyond that, some of the therapies raise serious ethical questions: A lobotomy irreversibly changes someone's personality. This wasn't just the wrong treatment. It was a radical move that turned people into zombies."

Mark attributes the use of such treatment to the fact that Israeli psychiatry was lagging behind the rest of the world.

"Until the 1980s, I think that Israeli psychiatry was 10 or 20 years behind what was happening in the West," he notes. "This derived, for one thing, from the language gap. The therapists of German origin implemented a European psychiatry which had disappeared after World War II, and they were unfamiliar with the therapeutic advances that occurred primarily in English-speaking countries. It wasn't until the late 1980s or early 1990s that psychiatric treatment in Israel fell into line with standard practice in the rest of the world."

Source: haaretz.com