Florida will exhume remains of 100 children who died at Dozier School for Boys

Source: nydailynews.com

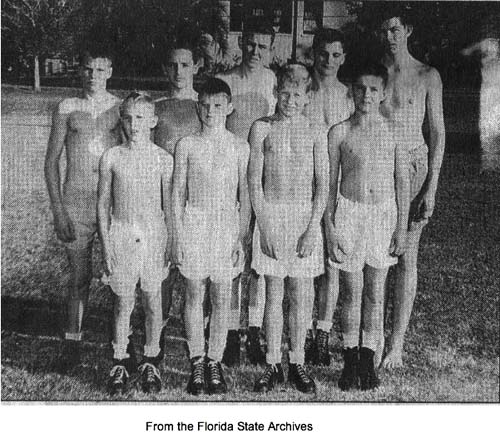

The notorious reform school was closed in 2011 following decades of reports that boys had been tortured.

The children in unmarked graves at a notorious Florida reform school will finally be allowed to tell their stories.

After years of pressure from families, Florida Gov. Rick Scott and the Florida Cabinet voted to allow researchers to exhume the human remains of dozens of children who died while attending the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys.

Researchers from the University of South Florida have identified more than 100 unmarked grave sites on the property of the state-owned school, which was closed in 2011 after decades of allegations that it routinely tortured boys who were sent there, WFLA News reported.

“A lot of us are seeking closure,” John Bonner, a Dozier resident from 1967 to 1969, told the Tampa Tribune. “A lot of people were abused there. A lot of people’s rights were trampled on. I was strapped with the belt so many times, one time just for looking at a supervisor the wrong way.”

Until Tuesday’s vote, Florida had blocked University of South Florida anthropologist Dr. Erin Kimmerle from exhuming the graves at the school.

In March, State Attorney General Pam Bondi had filed a petition to try to convince Scott to allow the researchers to begin identifying the bodies using DNA testing.

"The deaths that occurred at Dozier School for Boys in Marianna are cloaked in mystery, and the surviving family members deserve a thorough examination of the site," Bondi told WFLA.

Many boys who attended Dozier, which was approximately 60 miles west of Tallahassee, simply disappeared, leaving their families without answers about how, or whether, they were killed.

"This decision puts us a step closer to finishing the investigation," U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) said in response to Tuesday’s action by the governor and the cabinet. "Nothing can bring these boys back, but I’m hopeful that their families will now get the closure they deserve."

So far, USF researchers have been able to confirm the deaths of 96 children who were sent to the Dozier School between 1914 and 1973.

Article from: nydailynews.com

READ: For their own good: a St. Petersburg Times special report on child abuse at the Florida School for Boys

[...] Today, the state’s oldest reform school houses about 130 of the 6,000 juveniles in the custody of the Department of Juvenile Justice.

They are kept behind fences topped with razor wire, at a place where kids have been abused for 100 years. Over the years boys have been beaten here, shackled here, hog-tied here. Kept in isolation, driven so crazy they ate glass. Eight died in a fire here, neglected by guards. Hundreds of men who were beaten here in the 1950s and ’60s have sued the state. Dozens of boys are buried here on a little hill, their graves unidentified, the details forgotten.

What kind of place is the Dozier School for Boys today?

The Department of Juvenile Justice, citing the pending lawsuit and strict privacy laws, refused for months to let the St. Petersburg Times on campus to inspect conditions, interview boys or talk to staff. On Friday, as this story was headed to publication, DJJ officials agreed to schedule a visit.

For now, that leaves little more than the word of the state and the public record.

Using the state’s public information laws, the Times obtained more than 8,000 documents to better understand the school’s recent history. Those documents betray a place of abuse and neglect, of falsified records, bloody noses and broken bones.

In the past two years, according to the school’s own reports:

A suicidal boy drank cleaning fluid when no one was watching.

A boy so disturbed he threatened to cut off his finger to prove he wasn’t human climbed to a rooftop before guards could tackle him, breaking his arm.

Two boys went missing on campus for nine hours. Five staffers failed in their duties that day, and the superintendent of the high-security portion of Dozier didn’t report the incident. When it came to light, he resigned.

Another guard slapped an inmate during a basketball game, bloodying his nose. The boy asked to call the state’s abuse hotline, but was denied.

When an inmate is allowed to report abuse, the complaint goes to the state Department of Children and Families. In the past five years, DCF has opened 155 investigations at Dozier and verified seven cases of improper supervision, four of physical abuse, one of sexual abuse and one of medical mistreatment. An additional 33 cases had "some indicator" of abuse, mistreatment or neglect.

DCF’s investigative summaries were released by a judge after the Times argued that the public has good reason to see the records. According to those documents:

In January 2006, a guard grabbed a boy by the neck and head-butted him, breaking the boy’s nose.

In July 2006, a diabetic boy whose blood sugar was low was unresponsive for 20 minutes as two staffers ignored him. One staffer later quit and another, still on staff, was reprimanded.

One guard allegedly stuffed a boy in a laundry bag, and when the boy tried to chew through the strings, the guard encouraged others to scratch and pinch him. Investigators found "some indicators" of abuse: the boy’s bruises. Without video or witnesses, the allegations are sometimes impossible to prove. The guard resigned. [...] Source: TampaBay.com