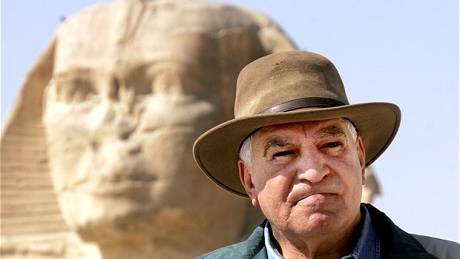

Golden Mummies: What Happened To The Indiana Jones Of Egypt?

Source: huffingtonpost.com

Zahi Hawass’ ego hasn’t suffered since protesters forced him out of his influential post as Egypt’s antiquities steward 18 months ago, shortly after Hosni Mubarak was toppled from the country’s presidency.

“I am Egyptian antiquities,” he says.

That confidence served him well when he controlled the pharaohs’ treasures on Mubarak’s behalf, steering Egypt’s economically critical Supreme Council of Antiquities and the billions it helped reap annually, primarily from tourism and international exhibitions. The man who calls himself Egypt’s Indiana Jones has fewer friends these days, now that revolution and a corruption scandal have forced him from office. Protesters who picketed Hawass and his Indy-esque fedora in Tahrir Square shouted that he should “take it with him and go.”

Though he was briefly restored to power last year, Hawass, 64, has yet to find much support among the Freedom and Justice Party of President-Elect Mohamed Morsi. He may yet be vindicated, however, if Morsi’s new government finds it can’t replace his golden touch. The stability of the fledgling democracy may even depend on it.

Before Mubarak’s fall in February, 2011, Hawass had spent more than two decades helping Egypt promote its antiquities to a foreign audience. He is credited as the man behind the traveling King Tut exhibit, the discovery of the Valley of the Golden Mummies and a wide range of other projects during his nine years as Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. He provided an agreeable face for the Western world.

Hawass’ aggressive promotion often came on the heels of tragedy, in what appeared to be a deft strumming of public sentiment toward his homeland. In 1998, following the murder of 63 tourists in Luxor, he reopened the Sphinx to the public after its 10-year closure. From then on, he organized a near-constant parade of blockbuster museum shows around the world designed to advertise Egypt as both an idea and destination.

In his absence, it remains unclear whether Egypt can make such economically crucial overtures to foreign tourists and whether the billions — and the goodwill — Hawass once brought in can ever come back without him.

“He created by his publicity campaigns a new image of Egypt that mobilized millions of visitors,” says Dieter Arnold, head of the Metropolitan Museum’s Egypt Department in New York. “He cleaned up the sites, built tourist facilities and museums, organized exhibitions abroad and brought Egyptian antiquities into the center of worldwide attention.”

For years, tourism had been the country’s largest economic sector. While the price of cotton fluctuated wildly and the number of ships passing through the Suez Canal plummeted after the global financial crisis, tourism proved resilient. In 2009, revenue dipped a slight 2% before thundering back in 2010 with more than 15% growth.

Still, by the first month of last year, as protests consumed Cairo, it had become clear that tourism alone would not be enough to keep the economy healthy. As the protests spread, the economy sank. The Tourism Ministry announced that revenue dropped by a third to $8.8 billion in 2011, but industry observers say the damage has been much worse. In addition to months of violence and instability, Tourism Ministry officials believe a rise in anti-western political posturing and extremist Islamic attitudes has contributed to leeriness among would-be visitors.

Hawass’s ubiquity, and his gift for gab, bred resentment among his fellow Egyptians, but the money he delivered quieted critics. Some 14.5 million visitors arrived in Egypt in 2010, many to tour the country’s historical sites. The billions they spent were vital to shoring up the country’s foreign reserves, which helped provide for such basic needs as wheat imports.

In essence, Hawass was putting bread on the table. Of course, that also involved painting a picture of Egypt that was tourist-friendly and glossed over some of the country’s brutal realities. Hawass’ Egypt was the pyramids and the pharoahs, not social, political and economic inequities on the streets of Cairo. Recruiting Western enthusiasts like assistants on his great dig, Hawass steered some of those same Westerners away from a deeper understanding of the tectonic shifts in Egyptian society that ultimately surfaced in Tahrir.

He also was never focused only on branding Egypt — he was busy branding himself as well. He mandated that the King Tut exhibition sell copies of his fedora and planned to launch an eponymous clothing line marketing shirts that his catalogue claimed, “Recall the rugged experience of excavating the ancient tombs in Egypt.”

Mubarak’s wife strongly supported Hawass, and he took the opportunity for financial gain. Hawass received $200,000 a year for serving as an Explorer-In-Residence for The National Geographic Society, which also helped arrange speaking engagements that earned him $15,000 apiece. In addition, he made an undisclosed sum from the sale of his books (each copy of “Secret Voyage: Love, Magic and Mysteries in the Realm of the Pharoah’s” sold for $4,400), as well as a reality TV show that he starred in, and his government salary. Though speculation about Hawass’s personal wealth became something of a sport among Egyptians frustrated by the Mubarak government’s lack of transparency, even those who saw him as the ultimate opportunist may be forced to accept him back into the fold if he can again funnel billions of dollars into the public purse.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if Hawass was reinstated as Minister,” says Nora Shalaby, an Egyptologist and political activist.

If Hawass makes a comeback, it will be a tribute to his charismatic tenacity and to the willingness of the new government to compromise democratic ideals in order to secure the country’s economy. Hawass’s weakness may be that he is a remnant of the old regime, but, in some ways, this is also his strength. He is an accomplished autocrat with little interest in public opinion and a demonstrated passion for showmanship. While his return would be politically unpopular, it might prove to be economically expedient.

“I’ll never stop caring about or working with Egypt’s history,” Hawass says.

SUDDEN POPULISM

Three days into the Cairo riots, as fire tore through the National Museum, thieves broke into the newly opened gift shop, stole tchotchkes and knocked over displays. Outside, smoke was billowing out of Mubarak’s party headquarters and across the city onto CNN. Rumors were spreading on Twitter: Protesters were looting the museum. Protesters were policing the museum. Police were looting the museum.

“Where is Zahi Hawass?”

[...]

Read the full article at: huffingtonpost.com

Also tune into Red Ice Radio:

Robert Bauval - Tutankhamun’s DNA, Zahi Hawass Chasing Mummies & Robert’s Egypt Tour

Andrew Collins - Egypt’s Underworld, Tomb of the Birds, Cave of the Snake & Secret Excavation Rumors

Robert Bauval - Post-Revolution Egypt

Christopher Dunn - The Hidden Chamber Behind Gantenbrink’s Door & The Giza Power Plant

Andrew Collins - Giza’s Cave Underworld Update

Carmen Boulter - The Pyramid Code, Band of Peace, The Migration of the Nile & Cosmic Cycles

Carmen Boulter - Pyramid Energy, The Age of the Sphinx & The Pyramids