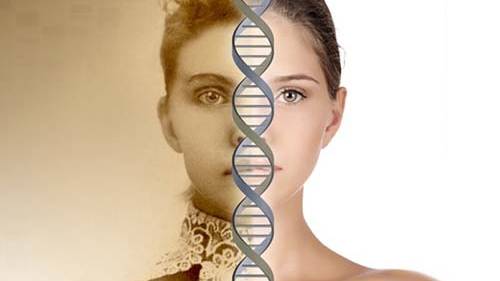

Grandma’s Experiences Leave a Mark on Your Genes

Source: discovermagazine.com

Your ancestors’ lousy childhoods or excellent adventures might change your personality, bequeathing anxiety or resilience by altering the epigenetic expressions of genes in the brain.

Darwin and Freud walk into a bar. Two alcoholic mice — a mother and her son — sit on two bar stools, lapping gin from two thimbles.

The mother mouse looks up and says, “Hey, geniuses, tell me how my son got into this sorry state.”

“Bad inheritance,” says Darwin.

“Bad mothering,” says Freud.

For over a hundred years, those two views — nature or nurture, biology or psychology — offered opposing explanations for how behaviors develop and persist, not only within a single individual but across generations.

And then, in 1992, two young scientists following in Freud’s and Darwin’s footsteps actually did walk into a bar. And by the time they walked out, a few beers later, they had begun to forge a revolutionary new synthesis of how life experiences could directly affect your genes — and not only your own life experiences, but those of your mother’s, grandmother’s and beyond.

The bar was in Madrid, where the Cajal Institute, Spain’s oldest academic center for the study of neurobiology, was holding an international meeting. Moshe Szyf, a molecular biologist and geneticist at McGill University in Montreal, had never studied psychology or neurology, but he had been talked into attending by a colleague who thought his work might have some application. Likewise, Michael Meaney, a McGill neurobiologist, had been talked into attending by the same colleague, who thought Meaney’s research into animal models of maternal neglect might benefit from Szyf’s perspective.

“I can still visualize the place — it was a corner bar that specialized in pizza,” Meaney says. “Moshe, being kosher, was interested in kosher calories. Beer is kosher. Moshe can drink beer anywhere. And I’m Irish. So it was perfect.”

The two engaged in animated conversation about a hot new line of research in genetics. Since the 1970s, researchers had known that the tightly wound spools of DNA inside each cell’s nucleus require something extra to tell them exactly which genes to transcribe, whether for a heart cell, a liver cell or a brain cell.

One such extra element is the methyl group, a common structural component of organic molecules. The methyl group works like a placeholder in a cookbook, attaching to the DNA within each cell to select only those recipes — er, genes — necessary for that particular cell’s proteins. Because methyl groups are attached to the genes, residing beside but separate from the double-helix DNA code, the field was dubbed epigenetics, from the prefix epi (Greek for over, outer, above).

Originally these epigenetic changes were believed to occur only during fetal development. But pioneering studies showed that molecular bric-a-brac could be added to DNA in adulthood, setting off a cascade of cellular changes resulting in cancer. Sometimes methyl groups attached to DNA thanks to changes in diet; other times, exposure to certain chemicals appeared to be the cause. Szyf showed that correcting epigenetic changes with drugs could cure certain cancers in animals.

Geneticists were especially surprised to find that epigenetic change could be passed down from parent to child, one generation after the next. A study from Randy Jirtle of Duke University showed that when female mice are fed a diet rich in methyl groups, the fur pigment of subsequent offspring is permanently altered. Without any change to DNA at all, methyl groups could be added or subtracted, and the changes were inherited much like a mutation in a gene.

Now, at the bar in Madrid, Szyf and Meaney considered a hypothesis as improbable as it was profound: If diet and chemicals can cause epigenetic changes, could certain experiences — child neglect, drug abuse or other severe stresses — also set off epigenetic changes to the DNA inside the neurons of a person’s brain? That question turned out to be the basis of a new field, behavioral epigenetics, now so vibrant it has spawned dozens of studies and suggested profound new treatments to heal the brain.

According to the new insights of behavioral epigenetics, traumatic experiences in our past, or in our recent ancestors’ past, leave molecular scars adhering to our DNA. Jews whose great-grandparents were chased from their Russian shtetls; Chinese whose grandparents lived through the ravages of the Cultural Revolution; young immigrants from Africa whose parents survived massacres; adults of every ethnicity who grew up with alcoholic or abusive parents — all carry with them more than just memories.

Like silt deposited on the cogs of a finely tuned machine after the seawater of a tsunami recedes, our experiences, and those of our forebears, are never gone, even if they have been forgotten. They become a part of us, a molecular residue holding fast to our genetic scaffolding. The DNA remains the same, but psychological and behavioral tendencies are inherited. You might have inherited not just your grandmother’s knobby knees, but also her predisposition toward depression caused by the neglect she suffered as a newborn.

[...]

Read the full article at: discovermagazine.com

Genetic Scars of the Holocaust: Children Suffer Too

[...] Psychologists have long been intrigued by the emotional profile of so-called second-generation Holocaust survivors. Parents who lived through the camps were forever changed by the horrors they witnessed. In the 21st century, many — probably most — would be recognized as suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Back then, the absence of such a diagnosis also meant the absence of effective treatments. As a result, a generation of children grew up in homes in which one, and sometimes both, parents were battling untold emotional demons at the same time they were going about the difficult business of trying to raise happy kids. No surprise, they weren’t always entirely successful.

Over the years, a large body of work has been devoted to studying PTSD symptoms in second-generation survivors, and it has found signs of the condition in their behavior and even their blood — with higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol, for example. The assumption — a perfectly reasonable one — was always that these symptoms were essentially learned. Grow up with parents afflicted with the mood swings, irritability, jumpiness and hypervigilance typical of PTSD and you’re likely to wind up stressed and high-strung yourself.

Now a new paper adds another dimension to the science, suggesting that it’s not just a second generation’s emotional profile that can be affected by a parent’s trauma; it may be their genes too. The study, published in the journal Biological Psychiatry, was conducted by a team led by neurobiologist Isabelle Mansuy of the University of Zurich. What she and her colleagues set out to explore went deeper than genetics in general, focusing instead on epigenetics — how genes change as a result of environmental factors in ways that can be passed onto the next generation.

To conduct their work, Mansuy’s team raised male mice from birth and continually but unpredictably separated them from their mothers from the time they were one day old until they were 14 days old. Thereafter, the animals were reared, fed and cared for normally, but the early trauma took its toll.

As adults, the subject animals exhibited PTSD-like symptoms such as isolation and jumpiness. More tellingly, their genes functioned differently from those of other mice. The investigators looked at five target genes associated with behavior—most notably, one that helps regulate the stress hormone CRF and one that regulates the neurotransmitter serotonin — and found that all of them were either overreactive or underreactive.

These mice, for the purposes of the study, were the equivalent of first-generation Holocaust survivors. They then fathered young and, like most males of the species, had nothing to do with their upbringing. The pups were raised by their mothers with none of the trauma and separation their fathers had suffered, and yet when they grew up, not only did they exhibit the same anxious behavior, but they also had the same signature gene changes.

"We saw the genetic differences both in the brains of the offspring mice and in the germline — or sperm — of the fathers," says Mansuy. [...]

Source: TIME

READ: Are genes our destiny? ’Hidden’ code in DNA evolves more rapidly than genetic code

Tune into Red Ice Radio:

Bruce Lipton - The Biology of Belief

Lenon Honor - Hour 1 - Male/Female Balance, Cosmic Respectability & 9/11 Trauma

Gregg Braden - Crisis in Thinking & False Assumptions of an Incomplete Science

Sonia Barrett - Destiny, Time, Space, Belief & Transcending the Levels of Programming

Barbara Hand Clow - Beyond Trauma & Acceleration of Consciousness

Michael Dunning - The Sacred Yew Tree: The Embryonic Tree of Life

Lloyd Pye - The Annunaki & Genetic Engineering

Lloyd Pye - Human Design & Properties of Annunaki Genes