The oceans of Jupiter’s ice worlds might be swimming with life — so why do we keep sending robots to Mars?

Source: aeon.co

The robots come to Mars out of a sky tinged peach from whirlwind-lofted dust.

They cut through the thin, cold air in supersonic aeroshells and parachutes, making planetfall in bouncing airbag cocoons and bursts of braking retrorockets, bristling with cameras and spectrometers, antennas and manipulator arms. Some stay where they land; others rove for years on end. Sniffing the air, sifting through soil, wheeling across a cratered landscape, the robots doggedly seek any wisp of Martian moisture, like lost desert travellers dying of thirst. They are looking for life, following a strategy that NASA officials describe as ‘following the water’.

This strategy pays heed to water’s eerie harmony with life: wherever one is found on Earth, the other isn’t far behind. There are good reasons to believe that water is the ideal cornerstone of biology, not only on Earth, but elsewhere in the Universe. All you need to make it is hydrogen and oxygen, respectively the first and third most abundant elements in the cosmos.

In liquid form, water is unparalleled in its attunement to life’s needs. It facilitates the transmission of biochemical energy, nutrients, and waste. It shapes the structures and interactions of proteins and other macromolecules. It shields against hostile cosmic radiation, and it has a remarkably robust capacity for retaining warmth. Most strangely, unlike almost every other substance in the Universe, when water freezes, it expands instead of contracting, forming a protective, insulating shell of ice at its surface. This helps oceans, lakes, and other liquid reservoirs avoid freezing solid when exposed to prolonged cold.

For researchers who study Mars, following the water has paid off handsomely. Every mission sent to Mars seeking water has found it and, as a result, we now know that our neighbouring world used to be a warmer, wetter, more habitable place. Billions of years ago, that all changed, as the planet cooled and lost most of its air and water, and settled into a quiet senescence. But present-day Mars still harbours a slumbering aquasphere, locked in the ground as ice, which may stir every so often, erupting to the surface in evanescent briny flows.

Officially, the next stage of NASA’s Mars exploration programme is to ‘seek signs of life’, a phase that supposedly began in the summer of 2012 with the successful landing of the car-sized Curiosity rover. It’s true that Curiosity can sniff out organic carbon in samples of Martian rock and soil, but it mostly seems to be following the water, too. So far, it has rolled through what looks to be an ancient dried-up riverbed, and found evidence suggesting that some of Mars’s ancient water was fresh enough to drink.

Whether there is or ever has been anything on Mars to actually drink it is, surprisingly, not a question that Curiosity is well-equipped to answer, though it should have lots of time to try. Thanks to its nuclear power source, Curiosity could roam for at least 14 years, long enough to be joined by several more planned orbiters, landers, and rovers, bringing the total number of robots investigating Mars to perhaps a dozen. For the foreseeable future, Mars will be the focal point of our planetary science, dwarfing all other efforts to explore elsewhere in the solar system.

Our current explorations of Mars have become cautious and procedural, perhaps to a fault, as a result of past overreaches in the search for Martian life. The strategy of following the water emerged in the long aftermath of NASA’s costly and ambitious Viking missions, which landed on Mars in 1976, seeking life and finding none. Mission-planners controversially included cameras in the Viking payloads, inspired by none other than Carl Sagan, who noted half-jokingly that a lander focused strictly on microbial life would risk missing any Martian polar bears that might wander by.

Of course, when the Vikings landed, no polar bears showed up, and no microbes did, either. Twenty years later, the chastened Mars-research community was still smarting from Viking’s sting and NASA held a press conference declaring that some of its scientists had discovered ‘microfossil’ evidence for life in a Martian meteorite. The microfossil interpretation was disputed before the ink dried on the breathless newspaper headlines, and within a few years it had been decisively debunked, but not before spawning a flurry of funding, which helped to produce today’s bumper crop of Martian robots.

Our obsession with Mars arises out of its similarity to Earth, and its nearness. Finding something clearly alien on the planet next door – some bacterium not built around DNA or RNA, for instance – would tell us that life arose independently on two separate worlds orbiting our solitary yellow star. We could no longer consider ourselves alone, for we would know with great confidence that life is a truly cosmic phenomenon, as inevitable in our Universe as the galaxies, stars, and planets themselves.

A strategy of following the water has become a necessary but insufficient placeholder for this grand ambition, and sadly we can now expect a decades-long interlude before the real story begins. The uncomfortable truth is that, despite the technical tour-de-force of our robotic reconnaissance, looking for water on Mars has become one of the most humdrum pursuits imaginable in all of 21st-century space science. It is the safest possible bet, the astrobiological equivalent of the bland-yet-filling casserole your in-laws sometimes make. Most news stories trumpeting yet another aqueous Martian discovery (or rediscovery) speak more to a collective public amnesia than to any paradigm-shifting knowledge being gained.

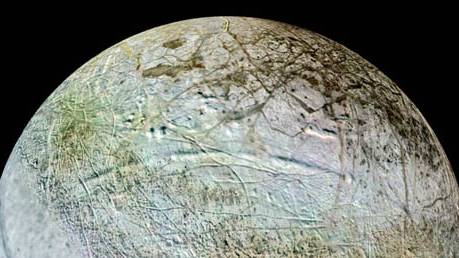

Indeed, scientists who specialise in Mars have been forced to dial down their dreams, hypothesising ever-smaller windows of opportunity for past life on the red planet, and ever more inaccessible refuges for anything now living there. Native Martians, if they exist at all, are most probably microbes clinging to life almost unreachably deep beneath the surface. This does not diminish the importance of exploring our neighbouring planet, but it must be admitted that there might well be more promising places to seek alien life. Indeed, if following the water is the prime directive in the search for extraterrestrial life, it increasingly appears that we should look beyond Mars to an icy moon of Jupiter called Europa.

[...]

Read the full article at: aeon.co