Why did men stop wearing high heels?

Source: bbc.co.uk

For generations they have signified femininity and glamour - but a pair of high heels was once an essential accessory for men.

Beautiful, provocative, sexy - high heels may be all these things and more, but even their most ardent fans wouldn’t claim they were practical.

They’re no good for hiking or driving. They get stuck in things. Women in heels are advised to stay off the grass - and also ice, cobbled streets and posh floors.

And high heels don’t tend to be very comfortable. It is almost as though they just weren’t designed for walking in.

Originally, they weren’t.

"The high heel was worn for centuries throughout the near east as a form of riding footwear," says Elizabeth Semmelhack of the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto.

Good horsemanship was essential to the fighting styles of the Persia - the historical name for modern-day Iran.

"When the soldier stood up in his stirrups, the heel helped him to secure his stance so that he could shoot his bow and arrow more effectively," says Semmelhack.

At the end of the 16th Century, Persia’s Shah Abbas I had the largest cavalry in the world. He was keen to forge links with rulers in Western Europe to help him defeat his great enemy, the Ottoman Empire.

A men’s 17th Century Persian shoe, covered in shagreen - horse-hide with pressed mustard seeds

So in 1599, Abbas sent the first Persian diplomatic mission to Europe - it called on the courts of Russia, Germany and Spain.

A wave of interest in all things Persian passed through Western Europe. Persian style shoes were enthusiastically adopted by aristocrats, who sought to give their appearance a virile, masculine edge that, it suddenly seemed, only heeled shoes could supply.

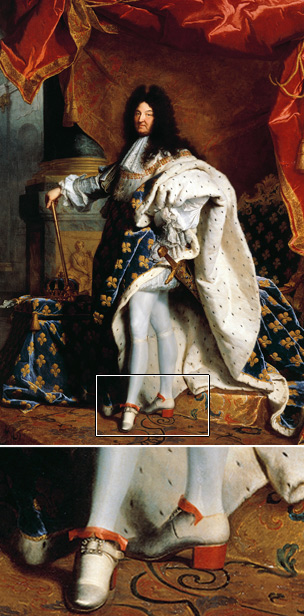

Louis XIV wearing his trademark heels in a 1701 portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud |

In the muddy, rutted streets of 17th Century Europe, these new shoes had no utility value whatsoever - but that was the point.

"One of the best ways that status can be conveyed is through impracticality," says Semmelhack, adding that the upper classes have always used impractical, uncomfortable and luxurious clothing to announce their privileged status.

"They aren’t in the fields working and they don’t have to walk far."

When it comes to history’s most notable shoe collectors, the Imelda Marcos of his day was arguably Louis XIV of France. For a great king, he was rather diminutively proportioned at only 5ft 4in (1.63m).

He supplemented his stature by a further 4in (10cm) with heels, often elaborately decorated with depictions of battle scenes.

The heels and soles were always red - the dye was expensive and carried a martial overtone. The fashion soon spread overseas - Charles II of England’s coronation portrait of 1661 features him wearing a pair of enormous red, French style heels - although he was over 6ft (1.85m) to begin with.

In the 1670s, Louis XIV issued an edict that only members of his court were allowed to wear red heels. In theory, all anyone in French society had to do to check whether someone was in favour with the king was to glance downwards. In practice, unauthorised, imitation heels were available.

Although Europeans were first attracted to heels because the Persian connection gave them a macho air, a craze in women’s fashion for adopting elements of men’s dress meant their use soon spread to women and children.

"In the 1630s you had women cutting their hair, adding epaulettes to their outfits," says Semmelhack.

"They would smoke pipes, they would wear hats that were very masculine. And this is why women adopted the heel - it was in an effort to masculinise their outfits."

From that time, Europe’s upper classes followed a unisex shoe fashion until the end of the 17th Century, when things began to change again.

"You start seeing a change in the heel at this point," says Helen Persson, a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. "Men started to have a squarer, more robust, lower, stacky heel, while women’s heels became more slender, more curvaceous."

The toes of women’s shoes were often tapered so that when the tips appeared from her skirts, the wearer’s feet appeared to be small and dainty.

Fast forward a few more years and the intellectual movement that came to be known as the Enlightenment brought with it a new respect for the rational and useful and an emphasis on education rather than privilege. Men’s fashion shifted towards more practical clothing. In England, aristocrats began to wear simplified clothes that were linked to their work managing country estates.

It was the beginning of what has been called the Great Male Renunciation, which would see men abandon the wearing of jewellery, bright colours and ostentatious fabrics in favour of a dark, more sober, and homogeneous look. Men’s clothing no longer operated so clearly as a signifier of social class, but while these boundaries were being blurred, the differences between the sexes became more pronounced.

"There begins a discussion about how men, regardless of station, of birth, if educated could become citizens," says Semmelhack.

"Women, in contrast, were seen as emotional, sentimental and uneducatable. Female desirability begins to be constructed in terms of irrational fashion and the high heel - once separated from its original function of horseback riding - becomes a primary example of impractical dress."

High heels were seen as foolish and effeminate. By 1740 men had stopped wearing them altogether.

But it was only 50 years before they disappeared from women’s feet too, falling out of favour after the French Revolution.

By the time the heel came back into fashion, in the mid-19th Century, photography was transforming the way that fashions - and the female self-image - were constructed.

[...]

Read the full article at: bbc.co.uk