Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation - First and Foremost a Military Measure

Source: theepochtimes.com

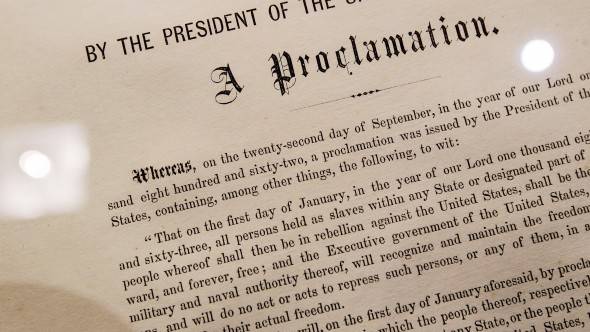

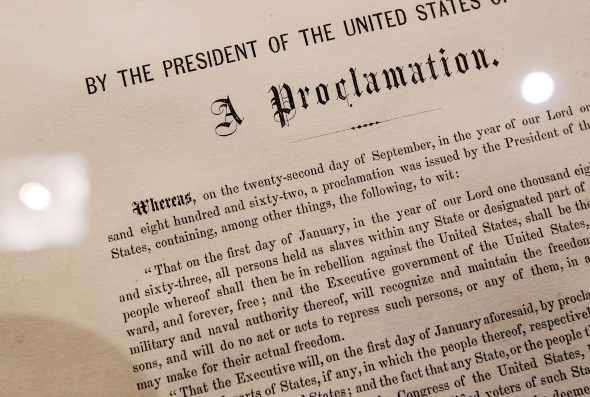

The Emancipation Proclamation—enacted exactly 150 years ago on Jan. 1, 2013—marked the beginning of the end for slavery in the United States, but historians say that the document was first and foremost a military measure.

“As you read the Emancipation Proclamation, you can see that there’s nothing eloquent about it,” said Margaret Washington, professor of history and American studies at Cornell University. “The term itself sounds eloquent, but if you read the document, it is specifically for purposes of war—and winning the war, either by military power or by forcing the south back into the union by virtue of emancipating their slaves.

Glancing back over the course of American history, it is impossible to separate the Civil War from the end of slavery. Nonetheless, in President Abraham Lincoln’s time, many considered the two developments mutually exclusive, even Lincoln himself.

A Progressive President

In his 1860 inaugural address, Lincoln promised to leave slavery alone in states where it already existed. In an 1862 New York Tribune letter, the president stated that his primary objective was saving the Union, and “not either to save or destroy slavery.”

In the midst of America’s bloodiest conflict—a war that pitted brother against brother—the Emancipation Proclamation offered a time-tested military strategy that would quickly bring the fighting to an end.

“That’s what was done with the American Revolution,” Washington said. “The British promised slaves freedom if they defected from the southern plantations in Virginia and came over to the British side and fought with them. Americans in the North used that same tactic with their slaves to fight against the British, and that’s how Northerners became free.”

While Lincoln stated for years that he was ethically opposed to slavery, he was no abolitionist. But the influence of the American anti-slavery movement had become a powerful cultural force, especially among radicals in Lincoln’s own Republican Party.

Washington’s freshman class traced the trajectory of this change in mindset by examining Lincoln’s writings and debate transcripts. These historical documents portray a man who had gone from tempering anti-slavery sentiment with a defense of white superiority, to suggesting weeks before his assassination that educated black men should be allowed to vote.

The celebrations that went around the world when the Emancipation Proclamation came across the telegraph lines were huge. And yet it didn’t really free anybody.

—Margaret Washington, professor of History and American Studies, Cornell University

“It was merely a suggestion, but you can see the way he’s moving at the time of his death,” Washington said. “He was becoming more and more progressive.”

Burning the Constitution

Even before Lincoln became president, much had already been done to end slavery in America. While abolitionists were driven by a moral imperative, slaveholders had the law on their side, and their interests remained legally protected by a formidable Democratic Party, which was solidly pro-slavery in both North and South.

However, the biggest legal hurdle to the anti-slavery effort was also a document fundamental to the nation—the U.S. Constitution.

“Abolitionists adored the Declaration of Independence, but they despised the Constitution. As a matter of fact, William Lloyd Garrison burned it in public,” Washington said.

The political might of early 19th-century slave owners can be seen in the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which obligated all U.S. citizens to send runaways back to their masters. Months after the law was passed, a fugitive that had escaped to Boston compelled the expense of thousands of troops to ensure his return.

At an anti-slave rally ignited by the absurdly expensive capture of this single fugitive, Garrison demonstrated abolitionist fury by burning copies of both the Slave Act and the Constitution—a document he described as a “covenant with death” and an “agreement with Hell.”

Although the Constitution did not contain the term “slave” until the practice was finally outlawed under the 13th Amendment, scholars say that the context is clear.

According to Washington, former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall confirmed the abolitionist attitude toward the Constitution.

“It was a pro-slavery document, except that the flexibility of the Constitution allowed it to have the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments that changed it,” Washington said.

[...]

Read the full article at: theepochtimes.com