The Queen Who Would Be King

Source: smithsonianmag.com

A scheming stepmother or a strong and effective ruler? History’s view of the pharaoh Hatshepsut changed over time.

It was a hot, dusty day in early 1927, and Herbert Winlock was staring at a scene of brutal destruction that had all the hallmarks of a vicious personal attack. Signs of desecration were everywhere; eyes had been gouged out, heads lopped off, the cobra-like symbol of royalty hacked from foreheads.

Winlock, head of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s archaeological team in Egypt, had unearthed a pit in the great temple complex at Deir el-Bahri, across the Nile from the ancient sites of Thebes and Karnak. In the pit were smashed statues of a pharaoh—pieces “from the size of a fingertip,” Winlock noted, “to others weighing a ton or more.” The images had suffered “almost every conceivable indignity,” he wrote, as the violators vented “their spite on the [pharaoh’s] brilliantly chiseled, smiling features.” To the ancient Egyptians, pharaohs were gods. What could this one have done to warrant such blasphemy? In the opinion of Winlock, and other Egyptologists of his generation, plenty.

The statues were those of Hatshepsut, the sixth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, one of the few—and by far the most successful—women to rule Egypt as pharaoh. Evidence of her remarkable reign (c. 1479-1458 b.c.) did not begin to emerge until the 19th century. But by Winlock’s day, historians had crafted the few known facts of her life into a soap opera of deceit, lust and revenge.

Although her long rule had been a time of peace and prosperity, filled with magnificent art and a number of ambitious building projects (the greatest of which was her mortuary, or memorial, temple at Deir el-Bahri), Hatshepsut’s methods of acquiring and holding onto power suggested a darker side to her reign and character. The widowed queen of the pharaoh Thutmose II, she had, according to custom, been made regent after his death in c. 1479 b.c. to rule for her young stepson, Thutmose III, until he came of age. Within a few years, however, she proclaimed herself pharaoh, thereby becoming, in the words of Winlock’s colleague at the Metropolitan, William C. Hayes, the “vilest type of usurper.” Disconcerting to some scholars, too, was her insistence on being portrayed as male, with bulging muscles and the traditional pharaonic false beard—variously interpreted by those historians as an act of outrageous deception, deviant behavior or both. Many early Egyptologists also concluded that Hatshepsut’s chief minister, Senenmut, must have been her lover as well, a co-conspirator in her climb to power, the so-called evil genius behind what they viewed as her devious politics.

Upon Hatshepsut’s death in c. 1458 b.c., her stepson, then likely still in his early 20s, finally ascended to the throne. By that time, according to Hayes, Thutmose III had developed “a loathing for Hatshepsut...her name and her very memory which practically beggars description.” The destruction of her monuments, carried out with such apparent fury, was almost universally interpreted as an act of long-awaited and bitter revenge on the part of Thutmose III, who, Winlock wrote, “could scarcely wait to take the vengeance on her dead that he had not dared in life.”

“Of course, it made a wonderful story,” says Renée Dreyfus, curator of ancient art and interpretation at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “And this is what we all read when we were growing up. But so much of what was written about Hatshepsut, I think, had to do with who the archaeologists were...gentlemen scholars of a certain generation.”

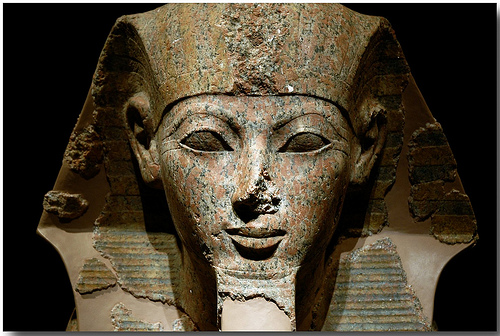

Osirian statues of Hatshepsut at her tomb, one stood at each pillar of the extensive structure, note the mummification shroud enclosing the lower body and legs as well as the crook and flail associated with Osiris

Hatshepsut was born at the dawn of a glorious age of Egyptian imperial power and prosperity, rightly called the New Kingdom. Her father, King Thutmose I, was a charismatic leader of legendary military exploits. Hatshepsut, scholars surmise, may have come into the world about the time of his coronation, c. 1504 b.c., and so would still have been a toddler when he famously sailed home to Thebes with the naked body of a Nubian chieftain dangling from the prow of his ship—a warning to all who would threaten his empire.

Hatshepsut seems to have idolized her father (she would eventually have him reburied in the tomb she was having built for herself) and would claim that soon after her birth he had named her successor to his throne, an act that scholars feel would have been highly unlikely. There had been only two—possibly three—female pharaohs in the previous 1,500 years, and each had ascended to the throne only when there was no suitable male successor available. (Cleopatra would rule some 14 centuries later.)

Normally, the pharaonic line passed from father to son—preferably the son of the queen, but if there were no such offspring, to the son of one of the pharaoh’s “secondary,” or “harem,” wives. In addition to Hatshepsut—and another younger daughter who apparently died in childhood—it’s believed that Thutmose I fathered two sons with Queen Ahmes, both of whom predeceased him. Thus the son of a secondary wife, Mutnofret, was crowned Thutmose II. In short order (and probably to bolster the royal bloodlines of this “harem child”), young Thutmose II was married to his half sister Hatshepsut, making her Queen of Egypt at about age 12.

[...]

Read the full article at: smithsonianmag.com