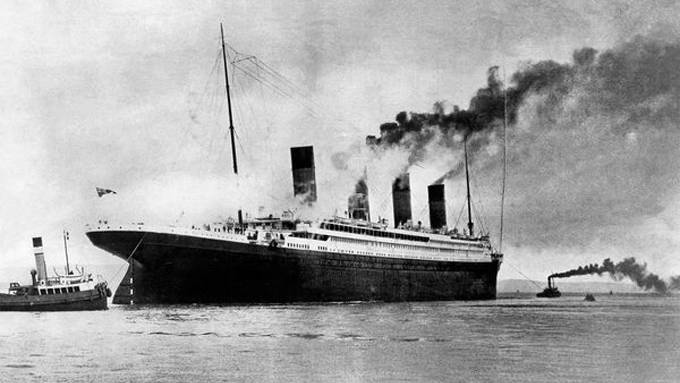

Titanic Sunk by "Supermoon" and Celestial Alignment?

Source: news.nationalgeographic.com

A rare astronomical assemblage might have helped sink R.M.S. Titanic.

Strong gravitational pull might have sent icebergs on a collision course.

Just weeks before the Titanic shipwreck’s hundredth anniversary, scientists have a brand-new theory as to what might have helped spur modern history’s most famous maritime disaster. (See pictures of Titanic’s rediscovery in 1985.)

An ultrarare alignment of the sun, the full moon, and Earth, they say, may have set the April 14, 1912, tragedy in motion, according to a new report.

R.M.S. Titanic went down on a moonless night, but the iceberg that sank the luxury liner may have been launched in part by a full moon that occurred three and a half months earlier, scientists say.

That full moon, on January 4, 1912, may have created unusually strong tides that sent a flotilla of icebergs southward—just in time for Titanic’s maiden voyage, said astronomer Donald Olson of Texas State University-San Marcos.

(Watch an animation of Titanic’s iceberg collision, breakup, and sinking.)

Blame It on the Moon?

Even at the time, spring 1912 was considered an unusually bad season for icebergs. But figuring out why this happened has been a mystery.

Olson believes the iceberg boom was the result of a rare combination of celestial phenomena, including a "supermoon": when the moon is full during its closest monthly approach to the Earth. (See supermoon pictures.)

During new and full moons, the sun, Earth, and the moon are arranged in a straight line, with the sun and moon intensifying each other’s gravitational pull on the planet. The result: Low tides are lower than usual, and high tides are higher—a phenomenon called a spring tide.

What’s more, on the January 4, 1912, the full moon—and therefore the spring-tide alignment—ended just six minutes before the moon made an unusually close swing by Earth.

It was the closest lunar approach, in fact, since A.D. 796, and Earth won’t see its like again until 2257. That combination of a very close moon and the celestial alignment added up to an especially strong gravitational pull on the Earth and therefore very high tides.

(See an interactive Titanic-wreck diagram).

Tidal Waves and Titanic

How would high tides hinder Titanic?

For starters, they could have flexed the tongues of glaciers extending out to sea in Greenlandic fjords, cracking off a bumper crop of southbound icebergs.

But icebergs don’t travel that fast. By April 14 new ones formed in that manner wouldn’t have gotten far enough to get in the Titanic’s way, Olson’s team concluded.

Rather, he said, the tides may have affected older icebergs that had run aground in shallow waters off Labrador and Newfoundland (map) in Canada (Titanic wreck-site map).

Often these icebergs are stranded until they melt enough to float again. But a high tide, Olson said, can refloat them.

And the unusually strong spring tide created on January 4 could have refloated a great many of them at once, sending a swarm of icebergs southward and into Titanic’s path, he said.

(Related: "Titanic Was Found During Secret Cold War Navy Mission.")

Against the Tide

It’s an interesting theory, but not everyone is convinced.

Astronomer Geza Gyuk, for example, doubts the January 4, 1912, spring tide was especially powerful.

Full and new moons coincide with the moon’s closest monthly approach of Earth every few years, with little effect on iceberg creation, said Gyuk, director of the Department of Astronomy at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium & Astronomy Museum.

Furthermore, in terms of tide-enhancing gravitational pull, it doesn’t make much difference whether a spring-tide alignment occurs within six minutes or a couple days of the moon’s closest approach, or perigee.

"A full moon anytime during the day preceding or following the perigee will have very close to the same tidal force," Gyuk said by email.

Also, he said, the moon on January 4, 1912, came only about 4,000 miles (6,200 kilometers) closer than its average perigee.

"The difference in tidal force between [the January 1912] perigee and an average perigee is only about 5 percent," he said.

Report co-author Olson doesn’t dispute any of this. Rather, he said, it doesn’t take a hugely stronger tide to refloat an iceberg.

"Suppose you pull a rowboat to a beach" at high tide and leave the boat when it first runs aground, he said. "It doesn’t have to be much of a higher tide to refloat the rowboat."

In addition, Olson said, "we have found several stories about record tides ... around the world in January 1912."

Source: nationalgeographic.com

For another theory see: Why They Sunk the Titanic